WHAT I HAVE WRITTEN (1996)

Randwick Ritz, Sydney:

6:00 PM

Monday May 05

Lido Cinemas, Melbourne:

6:00 PM

Monday May 12

Rating: MA15+

Duration: 102 minutes

Country: Australia

Language: English

Cast: Martin Jacobs, Gillian Jones, Jacek Koman, Angie Milliken

Director: John Hughes

SYDNEY TICKETS ⟶

MELBOURNE TICKETS ⟶

6:00 PM

Monday May 05

Lido Cinemas, Melbourne:

6:00 PM

Monday May 12

Rating: MA15+

Duration: 102 minutes

Country: Australia

Language: English

Cast: Martin Jacobs, Gillian Jones, Jacek Koman, Angie Milliken

Director: John Hughes

SYDNEY TICKETS ⟶

MELBOURNE TICKETS ⟶

4K RESTORATION – WORLD PREMIERE

“In the hands of director John Hughes this material is transformed into a fragmented, cool film that utilises many techniques, associated with art cinema….an impressive film that provides many entry points for the viewer by supplying just enough character development and narrative motivation to engage on an emotional level.” Geoff Mayer, The Oxford Companion to Australian Film

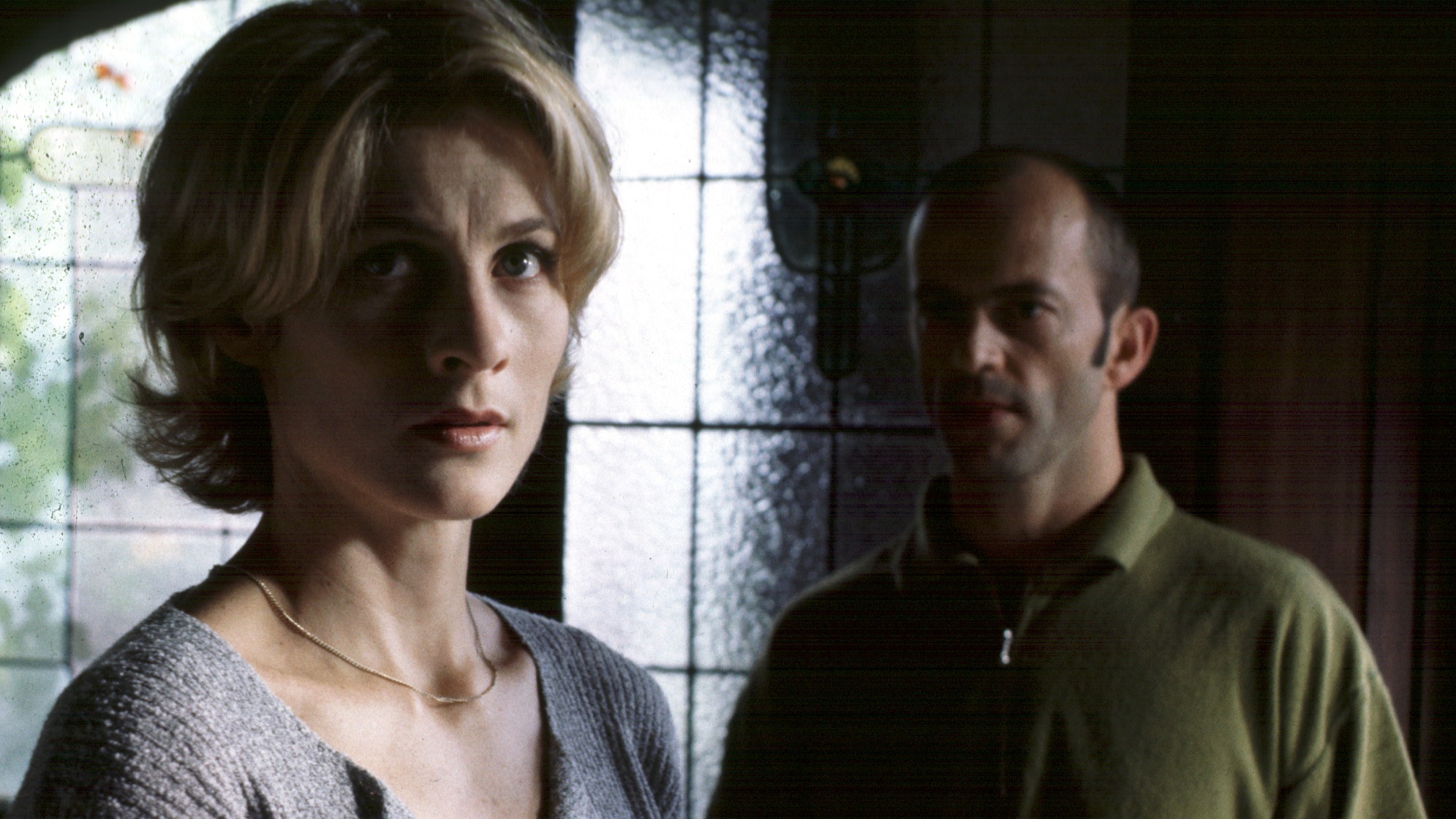

There are very few Australian films which draw their style and inspiration from European art cinema and the work of such masters as Alain Resnais and Chris Marker. What I Have Written, based on a novel by John Scott, is however such a film. It draws on those sources to present a twisting and complex narrative, intertwining two love stories – the first an erotic drama set in Australian academia, the second a story which draws on black and white photography and the Parisian setting from Marker’s legendary La Jetée. John Hughes, otherwise a master documentary maker for close to fifty years, took a detour into fictional drama that resembles the literary work of Marguerite Duras, Alain Robbe-Grillet and Michel Butor. As such it stands almost alone in the Australian cinema. The world premiere of this 4K restoration will be both a unique experience and a reminder that the Australian cinema has just occasionally been more than echoes of BBC drama, broad comedy and American genre re-treads.

Introduced by John Hughes at Ritz Cinemas and Lido Cinemas

A discussion with the filmmaker will be held after the screening in the upstairs mezzanine at the Ritz in Sydney and in the discussion space off the foyer at the Lido in Melbourne

“In the hands of director John Hughes this material is transformed into a fragmented, cool film that utilises many techniques, associated with art cinema….an impressive film that provides many entry points for the viewer by supplying just enough character development and narrative motivation to engage on an emotional level.” Geoff Mayer, The Oxford Companion to Australian Film

There are very few Australian films which draw their style and inspiration from European art cinema and the work of such masters as Alain Resnais and Chris Marker. What I Have Written, based on a novel by John Scott, is however such a film. It draws on those sources to present a twisting and complex narrative, intertwining two love stories – the first an erotic drama set in Australian academia, the second a story which draws on black and white photography and the Parisian setting from Marker’s legendary La Jetée. John Hughes, otherwise a master documentary maker for close to fifty years, took a detour into fictional drama that resembles the literary work of Marguerite Duras, Alain Robbe-Grillet and Michel Butor. As such it stands almost alone in the Australian cinema. The world premiere of this 4K restoration will be both a unique experience and a reminder that the Australian cinema has just occasionally been more than echoes of BBC drama, broad comedy and American genre re-treads.

Introduced by John Hughes at Ritz Cinemas and Lido Cinemas

A discussion with the filmmaker will be held after the screening in the upstairs mezzanine at the Ritz in Sydney and in the discussion space off the foyer at the Lido in Melbourne

FILM NOTES

By Anna Dzenis

By Anna Dzenis

Anna Dzenis is a screen studies lecturer, writer and editor.

JOHN HUGHES

John Hughes is an Australian independent filmmaker, producer, writer and director whose career spans over five decades of innovative experimental creative production. He has made over thirty non-fiction films and one dramatic feature film – What I have Written (1995). His filmography is diverse, encompassing documentaries for film and mainstream television, a dramatic feature film, art gallery installations and video art. His work is characterised by its formal experiments and investigations and his extensive archival research, and it is possible to identify several strands to his creative productions. These include hybrid speculative documentaries on international figures, such as philosopher Walter Benjamin – One Way Street (1992), and filmmaker Joris Ivens – Indonesia Calling: Joris Ivens in Australia (2009). One group of films that includes Menace (1976) and Traps (1985) traces some of the ways in which political stories are constructed, and their impact on government institutions and political figures. Another group of films explores Indigenous rights, colonialism and the institutional practices of racism in Australia. This includes sponsored films, such as Guwana (1982), Galiamble (1982), and Moments like These (1989); and independent films, After Mabo (1997), and River of Dreams (2000). (1) A triptych of Hughes’ work also examines the history and culture of independent filmmaking, by tracing a number of filmmakers’ organisations across several decades, and these films include Film-Work (1981), The Archive Project (2006) and his most recent film, Senses of Cinema (Hughes, Tom Zubrycki, 2022).

Throughout his career, Hughes has received numerous accolades for his contributions to Australian cinema. He was awarded the Stanley Hawes Award in 2006 and the Joan Long award for achievement in film history in the same year. He was also awarded the NSW Premier’s History Prize in the audio-visual category in 2007 and the Australian Writer’s Guild Best Broadcast Documentary award in 2010. Hughes’ extensive and significant impact on independent screen production in Australia has been documented in John Cumming’s book, The Films of John Hughes: a History of Independent Screen Production in Australia. (2)

Throughout his career, Hughes has received numerous accolades for his contributions to Australian cinema. He was awarded the Stanley Hawes Award in 2006 and the Joan Long award for achievement in film history in the same year. He was also awarded the NSW Premier’s History Prize in the audio-visual category in 2007 and the Australian Writer’s Guild Best Broadcast Documentary award in 2010. Hughes’ extensive and significant impact on independent screen production in Australia has been documented in John Cumming’s book, The Films of John Hughes: a History of Independent Screen Production in Australia. (2)

THE FILM

What I have Written (1995) tells the story of a secret love affair between Christopher and Frances that begins when Christopher is on sabbatical leave with his wife Sorel in Paris and is introduced to the bewitching Frances at a poetry reading. Christopher’s marriage to Sorel is falling apart and, when they return to Melbourne, his relationship with Frances continues through an exchange of increasingly sexually explicit letters. However, Christopher suffers a cerebral haemorrhage from which he does not recover. His colleague, art historian Jeremy, sends Sorel a novella that he claims has been written by Christopher, which tells the story of this affair, and which Jeremy says he wishes to publish posthumously. Sorel reads the novella and sets out on a detective-like mission to uncover the truth of the tale and the tellers. However, the heart of this film lies not so much in the story of affairs and betrayals but more in the collision of stories, in the remembering, misremembering, reinterpretations and retellings.

I originally watched What I have Written when it was released in the mid-1990s. (3) I remember being fascinated by an Australian fiction feature film that appeared to be influenced by some of the European art films that I loved. What I have Written was different from most other Australian films made around this time, because of these global art film influences but even more because of the way that it combined a formal experimental style with philosophical questions about what it means to read and interpret visual and literary texts. It was a self-conscious meta-film that engaged with questions about its own processes and the formal strategies of image making.

Rewatching the film today, one sees material traces of its origins in the 1990s, such as the slides and slide projectors that are used in an art history lecture, hybrid still/moving black and white sequences that are shot on analogue film, and hand-written manuscripts, amongst other technical markers. However, the questions that the film poses about how we read and interpret still and moving images, about what we learn and experience when a screen story is told in a formally experimental way, are questions that we are continuing to explore today.

The context of What I have Written’s production history is an interesting one. In the early 1990s the Australian film funding body, the Australian Film Commission (AFC), was transitioning from funding short films to funding feature films. It was a time when they decided to fund a number of low-budget experimental feature films that included Ross Gibson’s Dead to the World (1991), Susan Dermody’s Breathing Under Water (1992), Tracey Moffatt’s beDevil (1993) and John Hughes’ What I have Written (1995). (4) The fact that such an intellectually and aesthetically compelling group of films was made, and financially supported, at around the same time points to an important moment in Australian screen history and culture that warrants revisiting.

The source material for What I have Written is John A. Scott’s novel of the same name, with Scott also adapting his own novel into the screenplay. In an interview with Paul Kalina in Cinema Papers at the time of the film’s release, Hughes described how he first saw ‘an excerpt of the book in [the literary periodical] Scripsi and, as I read it, it announced itself as my next project ... I contacted John [Scott] and, on the basis of the full manuscript, commissioned a treatment. I had ideas about visual styles and so on, and we worked together to develop what we called an “expanded treatment”.’ (5)

Scott’s novel is structured into three distinct sections belonging in sequence to the characters, Christopher Houghton, Sorel Atherton and Jeremy Fayrfax. The film, however, is much more complex and layered, interweaving the past and present of the three main characters’ stories, juxtaposing different times, spaces and narrations. The characters Christopher, Sorel and Jeremy also “stand in” for, or are reimagined as, their fictional counterparts in scenes that are representations of the novella. Avery stands in for the poet Christopher Houghton (Martin Jacobs), Catherine stands in for the “other” woman Francis Bourin (Gillian Jones) and Avery’s wife, Gillian, stands in for Sorel Atheron (Angie Milliken). And so the depiction of the novella suggestively evokes memories of a past. But whose memories and whose past is ambiguous and uncertain.

The visual style of What I have Written is an experimental fresco, a layered and ambiguous mosaic of still and moving images with the boundaries between what is “real”, what is “imagined” and what is “fantasy” continuing to be blurred and mysterious. A number of films could be cited as references and inspirations. Interestingly, they are all films with distinctive visual styles, each in its own way exploring questions of “the image”. Hughes himself lists a number of points of departure for his visual conception of the film. They include Chris Marker’s La jetée (1962), Todd Haynes’ Poison (1991), Nicolas Roeg’s Bad Timing: A Sensual Obsession (1980) and the photographs of Bill Henson. (6) Lesley Stern, in her evocative article, ‘Severed Intensities. Conjuring John Hughes’ What I Have Written’, finds echoes of Alain Resnais’ L’année dernière à Marienbad (1961), a film that features grand architecture and disputed memories. (7) I can also see references to Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) and its detective-like investigation into the qualities, meaning and affects of images and Sophie Calle’s photo series, Suite Vénitienne (1980, 1996), in which the photographer follows a mysterious man from Paris through the streets of Venice, documenting this surveillance. In an essay for Artforum, ‘Character Study: Sophie Calle’ (8), art historian Yve-Alain Bois suggests that Calle’s photo series can be described through the Situationist Guy Debord’s concept of the dérive, ‘a technique of transient passage through varied ambiences’ a phrase that can be usefully applied to Hughes’ What I have Written. (9),

As in these films and photographs that have inspired Hughes’ film, so too in What I have Written it is not just the “reading” of images but the image itself that poses questions. This happens in many of the spaces and figurations in the film. It is there in Jeremy’s Freudian reading of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin, Child and Saint Anne. It is there in the sometimes still and at other times animated black and white images of people walking in Parisian streets and hotel rooms, as they appear and disappear and fragment. It is also there in the return to Melbourne when a realistic image inside a house suddenly appears to be a flashback or a memory. Hughes describes some of these ambiguities and visual slippages when he discusses elements of La jetée that influenced his film:

‘La jetée is this science-fiction work made by Marker in 1962 that proposes a very complex set of ideas about memory and the image, the recovery of memory and the past and the future, in which the meaning of moments recalled are in a constant state of transition. The central motif of the film is the walkway at the top of the Orly airport which is a space that is neither here nor there. It is the space of transition that the film works around on a number of layers and levels, and those things seem to me to become important reference points to What I have Written. It is continually about a kind of shifting between something and something else, an indeterminacy, present and non-present characters becoming quite different people.’ (10)

What I Have Written is a testament to John Hughes’ innovative filmmaking but it is also a prescient work that has anticipated current debates in screen studies. Its enduring relevance lies in its ability to provoke critical reflection on the nature of visual and textual interpretation, a topic that has only gained importance in our increasingly screen-dominated culture. As such, the film continues to contribute to ongoing discussions about the future of screen-based storytelling and the evolving relationships between viewers and visual texts.

Notes

1. Bill Mousoulis, ‘John Hughes’. Melbourne Independent Filmmakers website. https://www.innersense.com.au/mif/hughes.html

2. John Cumming, The Films of John Hughes: A History of Independent Screen Production in Australia. ATOM publications, St Kilda, 2014.

3. Anna Dzenis, ‘John Hughes’ What I have Written’. Metro magazine 107, 1996, pp. 21-24.

4. Cumming, p. 156.

5. Paul Kalina, interview with John Hughes, Cinema Papers 108, February 1996, p.8.

6. Cumming, p. 160

7. Lesley Stern, ‘Severed Intensities. Conjuring John Hughes’ What I have written’, Cinema Papers 108, February 1996, pp. 12 – 13.

8. Yve-Alain Bois, ‘Character Study: Sophie Calle’ Artforum, April 2000

9. Guy Debord, ‘Theory of the Dérive’, Les lèvres nues 9, November 1956, trans. Ken Knabb.

10. Kalina interview, as above, p. 9.

I originally watched What I have Written when it was released in the mid-1990s. (3) I remember being fascinated by an Australian fiction feature film that appeared to be influenced by some of the European art films that I loved. What I have Written was different from most other Australian films made around this time, because of these global art film influences but even more because of the way that it combined a formal experimental style with philosophical questions about what it means to read and interpret visual and literary texts. It was a self-conscious meta-film that engaged with questions about its own processes and the formal strategies of image making.

Rewatching the film today, one sees material traces of its origins in the 1990s, such as the slides and slide projectors that are used in an art history lecture, hybrid still/moving black and white sequences that are shot on analogue film, and hand-written manuscripts, amongst other technical markers. However, the questions that the film poses about how we read and interpret still and moving images, about what we learn and experience when a screen story is told in a formally experimental way, are questions that we are continuing to explore today.

The context of What I have Written’s production history is an interesting one. In the early 1990s the Australian film funding body, the Australian Film Commission (AFC), was transitioning from funding short films to funding feature films. It was a time when they decided to fund a number of low-budget experimental feature films that included Ross Gibson’s Dead to the World (1991), Susan Dermody’s Breathing Under Water (1992), Tracey Moffatt’s beDevil (1993) and John Hughes’ What I have Written (1995). (4) The fact that such an intellectually and aesthetically compelling group of films was made, and financially supported, at around the same time points to an important moment in Australian screen history and culture that warrants revisiting.

The source material for What I have Written is John A. Scott’s novel of the same name, with Scott also adapting his own novel into the screenplay. In an interview with Paul Kalina in Cinema Papers at the time of the film’s release, Hughes described how he first saw ‘an excerpt of the book in [the literary periodical] Scripsi and, as I read it, it announced itself as my next project ... I contacted John [Scott] and, on the basis of the full manuscript, commissioned a treatment. I had ideas about visual styles and so on, and we worked together to develop what we called an “expanded treatment”.’ (5)

Scott’s novel is structured into three distinct sections belonging in sequence to the characters, Christopher Houghton, Sorel Atherton and Jeremy Fayrfax. The film, however, is much more complex and layered, interweaving the past and present of the three main characters’ stories, juxtaposing different times, spaces and narrations. The characters Christopher, Sorel and Jeremy also “stand in” for, or are reimagined as, their fictional counterparts in scenes that are representations of the novella. Avery stands in for the poet Christopher Houghton (Martin Jacobs), Catherine stands in for the “other” woman Francis Bourin (Gillian Jones) and Avery’s wife, Gillian, stands in for Sorel Atheron (Angie Milliken). And so the depiction of the novella suggestively evokes memories of a past. But whose memories and whose past is ambiguous and uncertain.

The visual style of What I have Written is an experimental fresco, a layered and ambiguous mosaic of still and moving images with the boundaries between what is “real”, what is “imagined” and what is “fantasy” continuing to be blurred and mysterious. A number of films could be cited as references and inspirations. Interestingly, they are all films with distinctive visual styles, each in its own way exploring questions of “the image”. Hughes himself lists a number of points of departure for his visual conception of the film. They include Chris Marker’s La jetée (1962), Todd Haynes’ Poison (1991), Nicolas Roeg’s Bad Timing: A Sensual Obsession (1980) and the photographs of Bill Henson. (6) Lesley Stern, in her evocative article, ‘Severed Intensities. Conjuring John Hughes’ What I Have Written’, finds echoes of Alain Resnais’ L’année dernière à Marienbad (1961), a film that features grand architecture and disputed memories. (7) I can also see references to Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) and its detective-like investigation into the qualities, meaning and affects of images and Sophie Calle’s photo series, Suite Vénitienne (1980, 1996), in which the photographer follows a mysterious man from Paris through the streets of Venice, documenting this surveillance. In an essay for Artforum, ‘Character Study: Sophie Calle’ (8), art historian Yve-Alain Bois suggests that Calle’s photo series can be described through the Situationist Guy Debord’s concept of the dérive, ‘a technique of transient passage through varied ambiences’ a phrase that can be usefully applied to Hughes’ What I have Written. (9),

As in these films and photographs that have inspired Hughes’ film, so too in What I have Written it is not just the “reading” of images but the image itself that poses questions. This happens in many of the spaces and figurations in the film. It is there in Jeremy’s Freudian reading of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin, Child and Saint Anne. It is there in the sometimes still and at other times animated black and white images of people walking in Parisian streets and hotel rooms, as they appear and disappear and fragment. It is also there in the return to Melbourne when a realistic image inside a house suddenly appears to be a flashback or a memory. Hughes describes some of these ambiguities and visual slippages when he discusses elements of La jetée that influenced his film:

‘La jetée is this science-fiction work made by Marker in 1962 that proposes a very complex set of ideas about memory and the image, the recovery of memory and the past and the future, in which the meaning of moments recalled are in a constant state of transition. The central motif of the film is the walkway at the top of the Orly airport which is a space that is neither here nor there. It is the space of transition that the film works around on a number of layers and levels, and those things seem to me to become important reference points to What I have Written. It is continually about a kind of shifting between something and something else, an indeterminacy, present and non-present characters becoming quite different people.’ (10)

What I Have Written is a testament to John Hughes’ innovative filmmaking but it is also a prescient work that has anticipated current debates in screen studies. Its enduring relevance lies in its ability to provoke critical reflection on the nature of visual and textual interpretation, a topic that has only gained importance in our increasingly screen-dominated culture. As such, the film continues to contribute to ongoing discussions about the future of screen-based storytelling and the evolving relationships between viewers and visual texts.

Notes

1. Bill Mousoulis, ‘John Hughes’. Melbourne Independent Filmmakers website. https://www.innersense.com.au/mif/hughes.html

2. John Cumming, The Films of John Hughes: A History of Independent Screen Production in Australia. ATOM publications, St Kilda, 2014.

3. Anna Dzenis, ‘John Hughes’ What I have Written’. Metro magazine 107, 1996, pp. 21-24.

4. Cumming, p. 156.

5. Paul Kalina, interview with John Hughes, Cinema Papers 108, February 1996, p.8.

6. Cumming, p. 160

7. Lesley Stern, ‘Severed Intensities. Conjuring John Hughes’ What I have written’, Cinema Papers 108, February 1996, pp. 12 – 13.

8. Yve-Alain Bois, ‘Character Study: Sophie Calle’ Artforum, April 2000

9. Guy Debord, ‘Theory of the Dérive’, Les lèvres nues 9, November 1956, trans. Ken Knabb.

10. Kalina interview, as above, p. 9.

THE RESTORATION

Source: DCP John Hughes

The Restoration per Ray Argall

Director: John Hughes; Production Company: Early Works; Producers: John Hughes, Peter Sainsbury; Script: John A Scott, based on his novel; Photography: Dion Beebe; Editor: Uri Mizrahi; Production Design: Sarah Stollman; Art Direction: Fiona Greville; Set Decoration: Jill Eden; Costume Design: Kerri Mazzocco; Sound Design, Music: John Phillips and David Bridie with Helen Mountford

Cast: Martin Jacobs (Christopher/Avery), Gillian Jones (Frances/Catherine), Jacek Koman (Jeremy), Angie Milliken (Sorel/Gillian), Margaret Cameron (Clare Murnane), Nick Lathouris (Claude Murnane)

Australia | 1996 | 102 Mins | 4K DCP | Colour, B&W| English | MA15+

The Restoration per Ray Argall

Director: John Hughes; Production Company: Early Works; Producers: John Hughes, Peter Sainsbury; Script: John A Scott, based on his novel; Photography: Dion Beebe; Editor: Uri Mizrahi; Production Design: Sarah Stollman; Art Direction: Fiona Greville; Set Decoration: Jill Eden; Costume Design: Kerri Mazzocco; Sound Design, Music: John Phillips and David Bridie with Helen Mountford

Cast: Martin Jacobs (Christopher/Avery), Gillian Jones (Frances/Catherine), Jacek Koman (Jeremy), Angie Milliken (Sorel/Gillian), Margaret Cameron (Clare Murnane), Nick Lathouris (Claude Murnane)

Australia | 1996 | 102 Mins | 4K DCP | Colour, B&W| English | MA15+