THREE IN ONE

1:15PM, Saturday May 01, Randwick Ritz

Introduced by Graham Shirley

Director: Cecil Holmes

Country: Australia

Year: 1957

Runtime: 89 minutes

Language: English

Format: B&W, 35mm

Rating: G

Introduced by Graham Shirley

Director: Cecil Holmes

Country: Australia

Year: 1957

Runtime: 89 minutes

Language: English

Format: B&W, 35mm

Rating: G

Tickets ⟶

“…Full of energy

and promise. An honest and determined attempt to create a national style, it

may well be a landmark in the development of the Australian cinema.” — Pike & Cooper, Australian Film

1900-1977

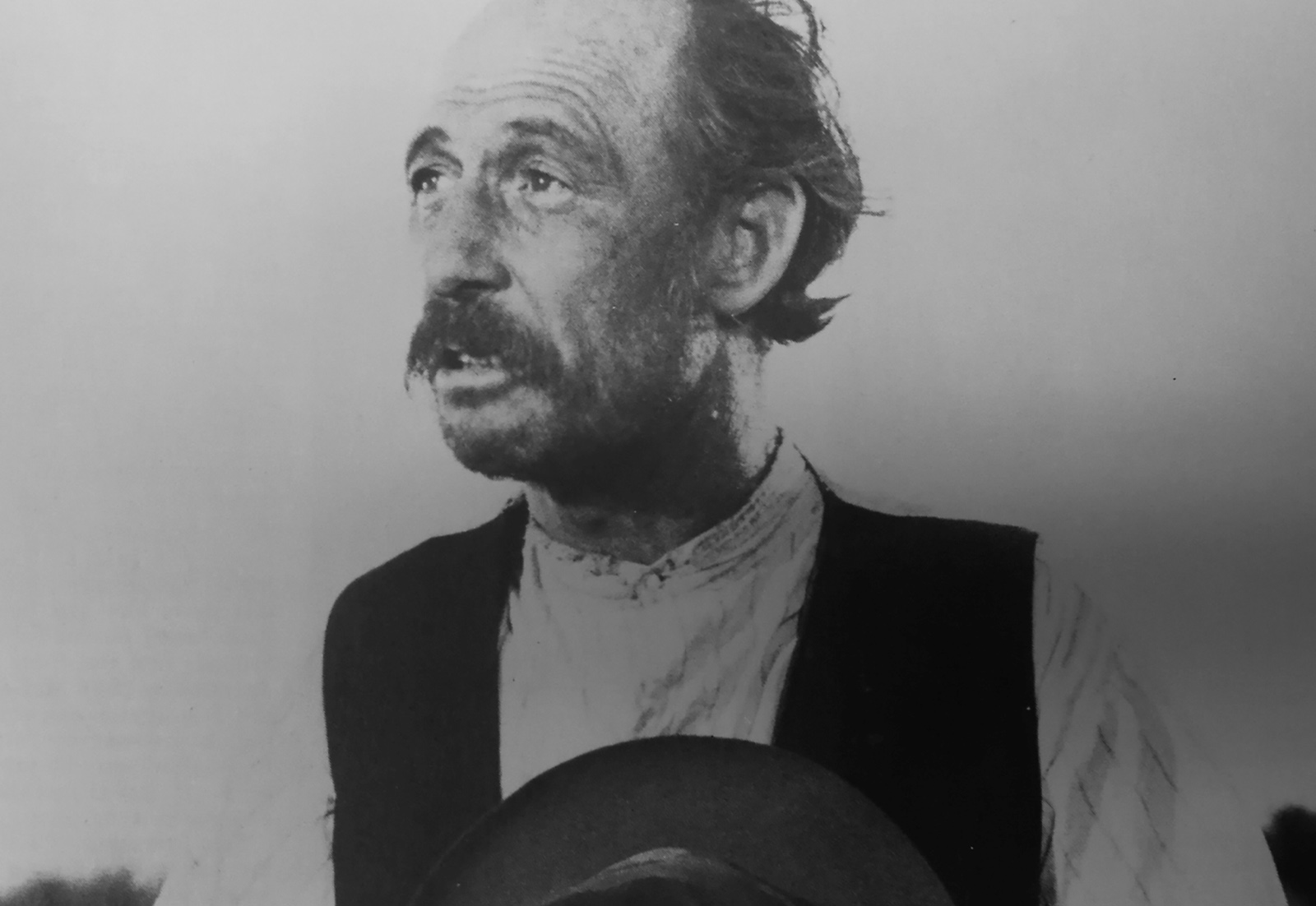

Cinema Reborn will be screening a beautiful, rarely-seen 35mm copy of Three in One from the NFSA collection. Starting out as an adaptation of a Frank Hardy story, Three in One became three stories; by Hardy, by Rex Rienits (adapting a Henry Lawson classic), and by Ralph Peterson, each with linking introductions by actor John McCallum. All three reflect on aspects of Australian life with a rare, straightforward honesty. Cecil Holmes, a film-maker of great talent, a committed leftist and champion for social justice, subsequently made a number of films for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies and the Commonwealth Film Unit.

This film will be screened on a 35mm print from the collection of the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

Cinema Reborn gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the NFSA.

Source: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia. Courtesy of Amanda Holmes-Tzafrir.

![]()

Cinema Reborn will be screening a beautiful, rarely-seen 35mm copy of Three in One from the NFSA collection. Starting out as an adaptation of a Frank Hardy story, Three in One became three stories; by Hardy, by Rex Rienits (adapting a Henry Lawson classic), and by Ralph Peterson, each with linking introductions by actor John McCallum. All three reflect on aspects of Australian life with a rare, straightforward honesty. Cecil Holmes, a film-maker of great talent, a committed leftist and champion for social justice, subsequently made a number of films for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies and the Commonwealth Film Unit.

This film will be screened on a 35mm print from the collection of the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

Cinema Reborn gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the NFSA.

Source: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia. Courtesy of Amanda Holmes-Tzafrir.

Amanda Holmes Tzarfir writes about her father Cecil Holmes:

Film Notes by Graham Shirley:

Cecil Holmes:

Quixotic, rebellious and drawn to trouble, Cecil Holmes belongs to a rare breed of radical adventurers who never give up. With a prodigious knowledge of the world, always a sharp eye in search of a story. He covered Hiroshima after the bomb. New Guinea on the brink of an uprising, Timor in the last days of Portuguese rule and Darwin laid waste by a cyclone. Narrowly escaping death squads in Mindanao, when writing his last book. His drive to make films and write screenplays, took him to Moscow, Peking, Budapest, New York and Hollywood, although back home in Australia he struggled to make ends meet.

Father, in your concrete office under our old tropical house where it was coolest, I sat quietly observing. The smell of stone, unfiltered 'Camels', carbon paper and rum pleasant in the humid air. Sitting tall at a well-beaten typewriter. The steady purpose of a humanist writing about mans inhumanity to man. I mused how the typewriter kept working after years of cigarette ash falling between the keys. Another lit one rests precariously on the lower lip as smoke hypnotically ebbs and flows, never drawn into the lungs. You stop to look up in thought, a brief adjustment of the black-rimmed glasses, a smile forms, clicking keys continue into the night. When the heat became oppressive we floated off East Arm in overly warm seawater, uncaring about watery predators. And never missed an opportunity to go to the pictures and talk about the film walking home. The backyard 'poets corner' with tree stumps and a few beers yielded visits from Douglas Lockwood, artist Yirawala, Don McLeod, Justice Dick Ward, Frank Hardy. Then away again to the wild places; Always to find dispossessed people struggling to survive and find justice in far flung places, to the great cities of the world, to the films and their makers, meeting actors, to writers and poets, to the battlers. One of his favourite quotes –

'While there is a lower class I am of it. While there is a soul in prison I am not free.' - Eugene Debs.

Cecil Holmes had already lived an incident-filled life by the time he came to make Three in One. New Zealand-born on 23 June 1921, he had his interest in film boosted by viewing Harry Watt’s documentary Night Mail (1936) on a double-bill with Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps (1935). During World War 2 he served with the New Zealand Air Force and the Royal Navy, being wounded when his ship was torpedoed. On a period of leave he witnessed feature production at England’s Denham Studios, and in 1945 he joined New Zealand’s National Film Unit (FPU). There Holmes directed vigorous, wide-ranging newsreel documentaries including Power from the River (1947), Mail Run (1947), and The Coaster (1948), the latter influenced by Night Mail in its chronicle of the activities of a coastal cargo ship. The strongest ingredient in Mail Run is the anti-colonialist contrast its images and narration draw between poor and well-to-do lifestyles in South East Asia, a perspective which earned Holmes an FPU warning not to rock the boat.

It was Holmes’ membership of the Communist Party of New Zealand that in 1948 sparked headlines when the Dominion newspaper printed a stolen letter containing details of his party membership. He was dismissed from the NFU, and then reinstated before deciding to resettle in Australia. There he directed The Food Machine (1950) for the Shell Film Unit and linked with fellow New Zealander Colin Scrimgeour, for whose company, Associated TV Pty Ltd, Holmes directed several short films followed by his debut feature, Captain Thunderbolt (1953). Made with originality and great visual flair, Holmes used his bushranging tale to champion the underdog, expose the brutality of establishment power and satirise racism. Captain Thunderbolt had limited Australian screenings in its original 69-minute form, and when released in the UK 1956 had been reduced to 56 minutes. But it was the film’s overseas release that earned Captain Thunderbolt £(Aust.)30,000, twice its cost. (Today, aside from a 35 mm trailer, Captain Thunderbolt survives only as a 16 mm TV version reduced to 53 minutes.)

Colin Scrimgeour purchased the lease of Sydney’s Pagewood studios, which after World War 2 had been re-equipped by Britain’s Ealing Studios. For several years Scrimgeour earned good money from the co-production Long John Silver (Byron Haskin, 1954) and its TV series spin-off. Ross Wood - talented cameraman of Captain Thunderbolt and Three in One - and Cecil Holmes later recalled that the Long John Silver experience proved excellent training for the Pagewood studio’s crew. By the time of Three in One (1957) the Pagewood team were highly skilled and coordinated.

Scrimgeour allowed Holmes to use these studios free of charge for Three in One, which originated when author Frank Hardy invited Holmes to make a film of his 1947 short story, The Load of Wood. Hardy invested £6,000 in the half-hour film and the remaining budget came from Melbourne advertising executive Julian Rose. The result impressed actor-producer John McCallum, who encouraged Holmes to add two more 30-minute segments to create a ‘portmanteau’ film (a genre much in vogue at that time). With additional money from Rose and other businessmen, Holmes filmed Joe Wilson’s Mates, adapted by scriptwriter Rex Rienits from Henry Lawson’s The Union Buries its Dead, and The City, an original script by Ralph Peterson.

The Film:

Aiming

to celebrate the spirit of Australian mateship between the 1890s and 1950s, Three

in One begins with Joe Wilson’s Mates. The story is about union

solidarity when a group of bush workers combine to pay for the funeral of a

stranger who was ‘a union man’. Holmes and Ross Wood showcase the pastoral hill

country through which Wilson’s heat-wearied, disparate procession of mourners

move, and the landscape of all three segments plays as strong a role as it had

in Captain Thunderbolt. The Load of Wood is the best of Three in One’s stories, having the

benefit of a decisive, well-paced storyline and sharp social commentary focussing

on two workers who covertly cut down a tree on a rich man’s farm to supply

winter fuel to the impoverished of a small town. Although the plot of The

City is less consequential, it has improved with the passing of the years as

a time capsule that skewers 1950s social attitudes. Its account of a young

couple whose plans to marry are blocked by the high price of housing

accentuates urban isolation when, after an argument, they go their separate

ways to wander night-time CBD Sydney. Mateship, when it does appear, is among

the hero’s fellow factory workers.

Cecil Holmes and Frank Hardy accompanied Three in One to the 1956 Karlovy Vary, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic) Film Festival, where it was awarded a prize as best film by a young director. John Alexander reported in Australia’s Tribune newspaper (5 Sep 1956) that compared with the American film Marty (Delbert Mann, 1955), which also screened at Karlovy Vary, Three in One was “a greater success” due to its “quiet and deep sincerity, a way of portraying Australian people”. John Madison for Sight and Sound in Autumn 1956 wrote that Three in One was “remarkably human and alive”. In May 1957, a Monthly Film Bulletin reviewer wrote: “Although an uneven film, Three in One is full of energy and promise. An honest and determined attempt to create a national style, it may well be a landmark in the development of the Australian cinema”.

Three in One was released internationally but failed to earn more than half its £28,000 budget. In Australia the film was screened in only several independent cinemas including western Sydney’s Royal Theatre at Chester Hill. Thanks to Ken G. Hall, chief executive of Sydney TV station TCN-9, the film was televised several times.

Cecil Holmes was one of very few directors trying to sustain a feature film career during the nadir of such filmmaking in Australia between 1950 and 1970. For the rest of his life, Holmes would attempt to raise funds for features which, however, would remain unmade. In the 1960s and 70s he directed a succession of well-regarded documentaries on Indigenous themes, including Lotu (1960), I the Aboriginal (1961), Faces in the Sun (1961) and Return to the Dreaming (1973). For the Institute of Aboriginal Studies (later AIATSIS), he made ethnographic films in collaboration with his second wife Sandra, who contributed research, liaison and sound recording. The films included Djalambu (1964), The Yabuduruwa Ceremony (1964) and The Lorrkun Ceremony of Croker Island (1964).

As Darwin-based editor of The Territorian magazine and an activist in the 1960s, Holmes worked alongside Indigenous leaders in their fight for citizenship as well as equal rights and pay. His most significant film in the three years he worked at Film Australia in the early 1970s was the dramatised documentary Gentle Strangers (1972), which depicted challenges faced in Australia by Asian students. For much of that decade he was a mentor and writer for a new generation of Australian feature film producers and directors. He died on 24 August 1994.

Cecil Holmes and Frank Hardy accompanied Three in One to the 1956 Karlovy Vary, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic) Film Festival, where it was awarded a prize as best film by a young director. John Alexander reported in Australia’s Tribune newspaper (5 Sep 1956) that compared with the American film Marty (Delbert Mann, 1955), which also screened at Karlovy Vary, Three in One was “a greater success” due to its “quiet and deep sincerity, a way of portraying Australian people”. John Madison for Sight and Sound in Autumn 1956 wrote that Three in One was “remarkably human and alive”. In May 1957, a Monthly Film Bulletin reviewer wrote: “Although an uneven film, Three in One is full of energy and promise. An honest and determined attempt to create a national style, it may well be a landmark in the development of the Australian cinema”.

Three in One was released internationally but failed to earn more than half its £28,000 budget. In Australia the film was screened in only several independent cinemas including western Sydney’s Royal Theatre at Chester Hill. Thanks to Ken G. Hall, chief executive of Sydney TV station TCN-9, the film was televised several times.

Cecil Holmes was one of very few directors trying to sustain a feature film career during the nadir of such filmmaking in Australia between 1950 and 1970. For the rest of his life, Holmes would attempt to raise funds for features which, however, would remain unmade. In the 1960s and 70s he directed a succession of well-regarded documentaries on Indigenous themes, including Lotu (1960), I the Aboriginal (1961), Faces in the Sun (1961) and Return to the Dreaming (1973). For the Institute of Aboriginal Studies (later AIATSIS), he made ethnographic films in collaboration with his second wife Sandra, who contributed research, liaison and sound recording. The films included Djalambu (1964), The Yabuduruwa Ceremony (1964) and The Lorrkun Ceremony of Croker Island (1964).

As Darwin-based editor of The Territorian magazine and an activist in the 1960s, Holmes worked alongside Indigenous leaders in their fight for citizenship as well as equal rights and pay. His most significant film in the three years he worked at Film Australia in the early 1970s was the dramatised documentary Gentle Strangers (1972), which depicted challenges faced in Australia by Asian students. For much of that decade he was a mentor and writer for a new generation of Australian feature film producers and directors. He died on 24 August 1994.

Notes by Adrian Danks:

G’day Comrade: Cecil Holmes’s Three in One

Cecil Holmes’s Three in One (1957) represents one of the highpoints of

post-war Australian cinema, reframing the common or characteristic theme of

“mateship” within more explicitly leftist contexts. But what is most remarkable

about the film – which is admittedly uneven in quality, possibly inevitably so

considering its tripartite form – is its visual style, both reaffirming and

transforming the common preoccupations commonly found in Australian landscape

cinema. Also significant are the international models of filmmaking aesthetics

that it openly draws upon, ranging from Soviet Montage to Italian neorealism.

These plainly visible influences also betray Holmes’s cinephilia; he was a key

figure in the New Zealand film society movement of the 1940s, and ran a

company, New Dawn Films, that distributed European cinema later in the 1950s.

It is nevertheless the middle section of Three in One, based Frank Hardy’s short story “The Load of Wood”, that remains a classic Australian expression of colloquial understatement, providing a minimally worded, visually high contrast and largely location-shot paean to worker unity during the bleak days of the 1930s Depression. Such a bold emphasis was not surprising as both Captain Thunderbolt (1953), the director’s previous feature, and Three in One were funded independently by companies or figures sympathetic to Holmes’s leftist views.

Three in One, self-evidently, contains three separate stories surveying the distinctively Australian theme of “mateship”, introduced by the somewhat plumy tones of significant “local” star John McCallum who is “captured” relaxing between performances of Terence Rattigan’s The Deep Blue Sea in his Theatre Royal (Sydney) dressing room. This trilogy of ostensibly stand-alone short films moves in time from the 1890s through the early Great Depression to the hustle-and-bustle of modern mid-1950s Sydney. Though thematically related, each of the three stories takes a different tone and approach, ranging from the initial, often comic, sun-scorched adaptation of Henry Lawson’s profoundly laconic “The Union Buries its Dead”, titled “Joe Wilson’s Mates”, through the atmospheric, isolated, low-key night-time rural setting of “The Load of Wood”, to the more anonymous – though distinctly Sydney-set – treatment of Ralph Peterson’s original story and script, “The City”. The first two stories of Three in One, in particular, highlight the relation of figures to iconic and distinctive Australian landscapes, though each is equally preoccupied with what might constitute community in each of these isolated environments and situations. The closer the film gets to the present day the more it moves away from such conceptions of community, the final part focusing predominantly on the more conventional cinematic and narratological framework of the romantic couple. But even in this final section – which presents an uncommonly gritty view of Australian life – the couple are characteristically assisted by their workmates and the communal possibilities of modern life are subtly indicated.

Although rarely screened, Three in One is one of the most singular, significant and impressive features made in Australian between World War II and the film revival of the 1970s. The only truly local feature film released in 1957, it is a profoundly independent work that robustly demonstrates Holmes’s idiosyncratic and visionary filmmaking capabilities. A significant aesthetic advance on the more piecemeal triumphs ofCaptain Thunderbolt, Three in One nevertheless failed to attain a proper Australian commercial release on its completion, individual episodes ultimately being screened as supporting shorts by a local exhibitor. This sits in contrast to the film’s international distribution which, although hardly lucrative, saw it being released in numerous European countries and New Zealand, and garnering awards and strong critical notices at the Edinburgh and Karlovy Vary film festivals in 1956.

The strongest section of Three in One is definitely its middle one. Initially designed as a short film in its own right, and financed by the European earnings of Hardy’s celebrated novelPower Without Glory, “The Load of Wood” is a brilliantly shot – by the great Ross Wood – and acted two-hander that evocatively summons up a palpably chilly atmosphere and tension.

In many respects, the opening story is the weakest, and is certainly the most leisurely and digressive entry in the trilogy. It does feature some striking exterior shots with low-angle framing, creating vistas that are reminiscent of late 1920s Soviet cinema, a key point of reference for both Holmes’s visual style and his politics. But despite its pro-union stance, and display of game leftist sympathies in the context of the Cold War and a broader environment of anti-communism, this initial section is more concerned with creating a jovial atmosphere around the two songs contributed by a folk group (The Bushwacker’s Band, a group entirely distinct from the later and more famous, The Bushwackers) than any truly potent political or social message – though the use of such revived “folk” materials and sensibilities was also integral to leftist culture and social justice in this period.

The final section, “The City”, is both more conventional and somewhat bleaker than the two that precede it. It is also the section that moves farthest away from the broader concept of “mateship”. This “short” is less remarkable for the somewhat mundane domestic drama that unfolds – involving a young couple despairing about the cost of housing and stalling their marriage as a result – than its portrait of night-time Sydney (complete with a stark Sydney Harbour Bridge) as a hive of activity and forbidding shadows. Although far from film noir in its broader sensibility, the visual stamp of this imposing style certainly makes its mark. But Holmes’s model is equally that of neorealism, a key stylistic, thematic and, most importantly, ethical benchmark throughout his fiction and documentary work. In this regard, it is telling that the film’s poster promotes it, if somewhat hyperbolically, as “AUSTRALIA’S FIRST REALIST FILM”. Three in One stands, for all its inconsistencies, as Holmes’s greatest, and most dynamic and iconic contribution to Australian cinema.

Adrian Danks note above is an extended and amended version of an article that first appeared in Directory of World Cinema: Australia & New Zealand, edited by Ben Goldsmith and Geoff Lealand (Intellect: Bristol and Chicago, 2010): 26-27.

It is nevertheless the middle section of Three in One, based Frank Hardy’s short story “The Load of Wood”, that remains a classic Australian expression of colloquial understatement, providing a minimally worded, visually high contrast and largely location-shot paean to worker unity during the bleak days of the 1930s Depression. Such a bold emphasis was not surprising as both Captain Thunderbolt (1953), the director’s previous feature, and Three in One were funded independently by companies or figures sympathetic to Holmes’s leftist views.

Three in One, self-evidently, contains three separate stories surveying the distinctively Australian theme of “mateship”, introduced by the somewhat plumy tones of significant “local” star John McCallum who is “captured” relaxing between performances of Terence Rattigan’s The Deep Blue Sea in his Theatre Royal (Sydney) dressing room. This trilogy of ostensibly stand-alone short films moves in time from the 1890s through the early Great Depression to the hustle-and-bustle of modern mid-1950s Sydney. Though thematically related, each of the three stories takes a different tone and approach, ranging from the initial, often comic, sun-scorched adaptation of Henry Lawson’s profoundly laconic “The Union Buries its Dead”, titled “Joe Wilson’s Mates”, through the atmospheric, isolated, low-key night-time rural setting of “The Load of Wood”, to the more anonymous – though distinctly Sydney-set – treatment of Ralph Peterson’s original story and script, “The City”. The first two stories of Three in One, in particular, highlight the relation of figures to iconic and distinctive Australian landscapes, though each is equally preoccupied with what might constitute community in each of these isolated environments and situations. The closer the film gets to the present day the more it moves away from such conceptions of community, the final part focusing predominantly on the more conventional cinematic and narratological framework of the romantic couple. But even in this final section – which presents an uncommonly gritty view of Australian life – the couple are characteristically assisted by their workmates and the communal possibilities of modern life are subtly indicated.

Although rarely screened, Three in One is one of the most singular, significant and impressive features made in Australian between World War II and the film revival of the 1970s. The only truly local feature film released in 1957, it is a profoundly independent work that robustly demonstrates Holmes’s idiosyncratic and visionary filmmaking capabilities. A significant aesthetic advance on the more piecemeal triumphs ofCaptain Thunderbolt, Three in One nevertheless failed to attain a proper Australian commercial release on its completion, individual episodes ultimately being screened as supporting shorts by a local exhibitor. This sits in contrast to the film’s international distribution which, although hardly lucrative, saw it being released in numerous European countries and New Zealand, and garnering awards and strong critical notices at the Edinburgh and Karlovy Vary film festivals in 1956.

The strongest section of Three in One is definitely its middle one. Initially designed as a short film in its own right, and financed by the European earnings of Hardy’s celebrated novelPower Without Glory, “The Load of Wood” is a brilliantly shot – by the great Ross Wood – and acted two-hander that evocatively summons up a palpably chilly atmosphere and tension.

In many respects, the opening story is the weakest, and is certainly the most leisurely and digressive entry in the trilogy. It does feature some striking exterior shots with low-angle framing, creating vistas that are reminiscent of late 1920s Soviet cinema, a key point of reference for both Holmes’s visual style and his politics. But despite its pro-union stance, and display of game leftist sympathies in the context of the Cold War and a broader environment of anti-communism, this initial section is more concerned with creating a jovial atmosphere around the two songs contributed by a folk group (The Bushwacker’s Band, a group entirely distinct from the later and more famous, The Bushwackers) than any truly potent political or social message – though the use of such revived “folk” materials and sensibilities was also integral to leftist culture and social justice in this period.

The final section, “The City”, is both more conventional and somewhat bleaker than the two that precede it. It is also the section that moves farthest away from the broader concept of “mateship”. This “short” is less remarkable for the somewhat mundane domestic drama that unfolds – involving a young couple despairing about the cost of housing and stalling their marriage as a result – than its portrait of night-time Sydney (complete with a stark Sydney Harbour Bridge) as a hive of activity and forbidding shadows. Although far from film noir in its broader sensibility, the visual stamp of this imposing style certainly makes its mark. But Holmes’s model is equally that of neorealism, a key stylistic, thematic and, most importantly, ethical benchmark throughout his fiction and documentary work. In this regard, it is telling that the film’s poster promotes it, if somewhat hyperbolically, as “AUSTRALIA’S FIRST REALIST FILM”. Three in One stands, for all its inconsistencies, as Holmes’s greatest, and most dynamic and iconic contribution to Australian cinema.

Adrian Danks note above is an extended and amended version of an article that first appeared in Directory of World Cinema: Australia & New Zealand, edited by Ben Goldsmith and Geoff Lealand (Intellect: Bristol and Chicago, 2010): 26-27.

Full film details:

Credits:

Australia | 1957 | 89 mins | B&W | Sound | 35mm

| English | G

Dir/Prod: Cecil HOLMES | Prod Co: Australian Tradition Films | Scr: Rex RIENITS, based on stories by Henry Lawson (The Union Buries its Dead) & Frank Hardy (A Load of Wood), Ralph PETERSON | Photo: Ross WOOD | Edit: A. William COPELAND | Sound: Hans WETZEL | Music: Raymond HANSON

Cast: (“Joe Wilson’s Mates”) Edmund ALLISON (Tom Stevens), Reg LYE (the swaggie), Alexander ARCHDALE (Firbank) (“The Load of Wood”) Jock LEVY (Darkie), Leonard Thiele (Ernie) (“The City) Joan LANDOR (Kathy), Brian VICARY (Ted), Betty LUCAS (Freda), Gordon GLENWRIGHT (Alex)

Source: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

Thanks to Amanda HOLMES-TZAFRIR

Dir/Prod: Cecil HOLMES | Prod Co: Australian Tradition Films | Scr: Rex RIENITS, based on stories by Henry Lawson (The Union Buries its Dead) & Frank Hardy (A Load of Wood), Ralph PETERSON | Photo: Ross WOOD | Edit: A. William COPELAND | Sound: Hans WETZEL | Music: Raymond HANSON

Cast: (“Joe Wilson’s Mates”) Edmund ALLISON (Tom Stevens), Reg LYE (the swaggie), Alexander ARCHDALE (Firbank) (“The Load of Wood”) Jock LEVY (Darkie), Leonard Thiele (Ernie) (“The City) Joan LANDOR (Kathy), Brian VICARY (Ted), Betty LUCAS (Freda), Gordon GLENWRIGHT (Alex)

Source: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

Thanks to Amanda HOLMES-TZAFRIR