THE TRIAL (1962)

3:00PM, Saturday April 29

8:15PM, Tuesday May 02

Randwick Ritz

Director: Orson Welles

Country: Germany, France, Italy

Year: 1962

Runtime: 120 minutes

Rating: PG

Language: English

TICKETS ⟶

8:15PM, Tuesday May 02

Randwick Ritz

Director: Orson Welles

Country: Germany, France, Italy

Year: 1962

Runtime: 120 minutes

Rating: PG

Language: English

TICKETS ⟶

THE TRIAL/ LE PROCÈS

4K RESTORATION

"Orson Welles's nightmarish, labyrinthine comedy of 1962 remains his creepiest and most disturbing work; it's also a lot more influential than most people admit." — Jonathan Rosenbaum

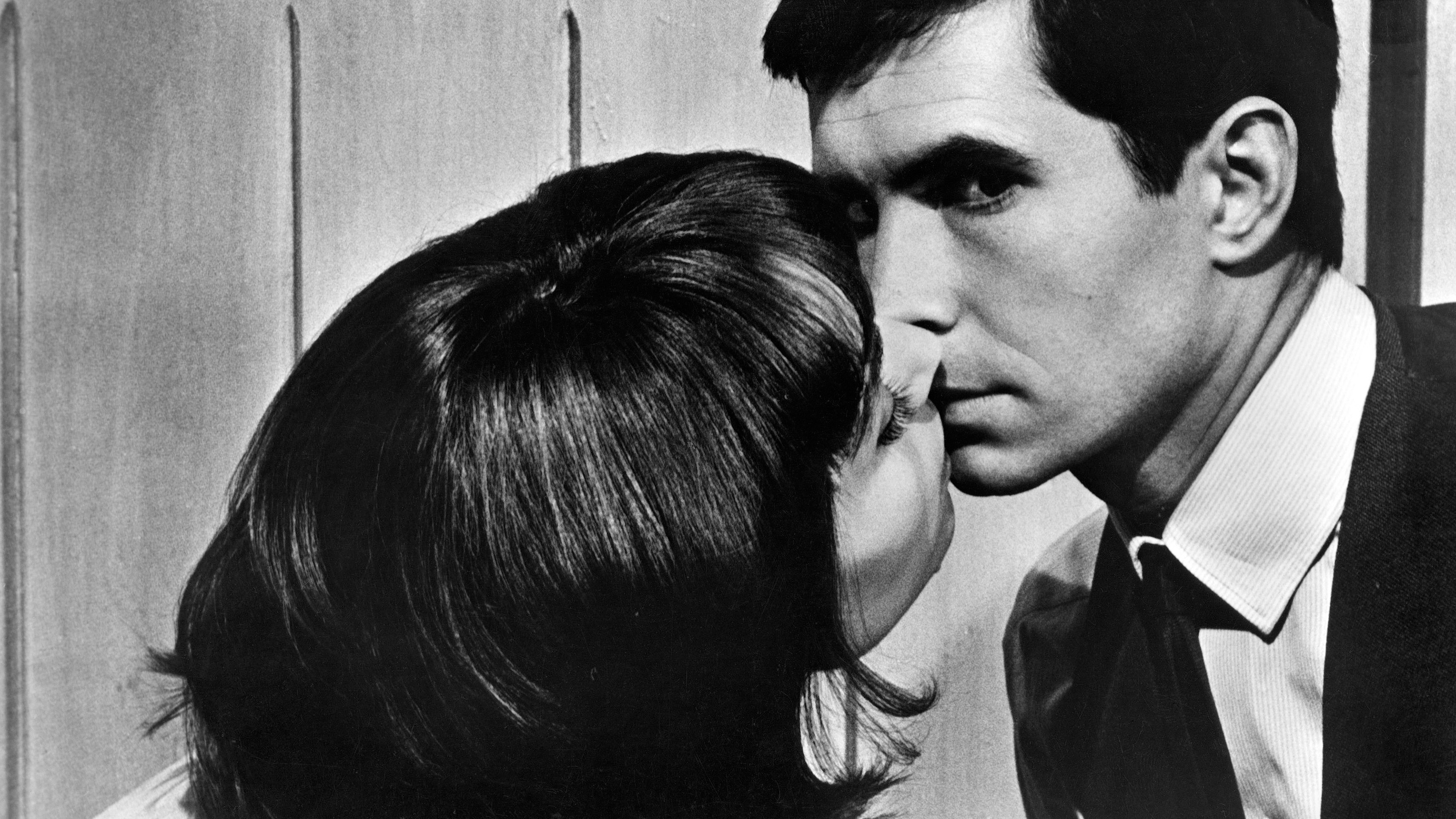

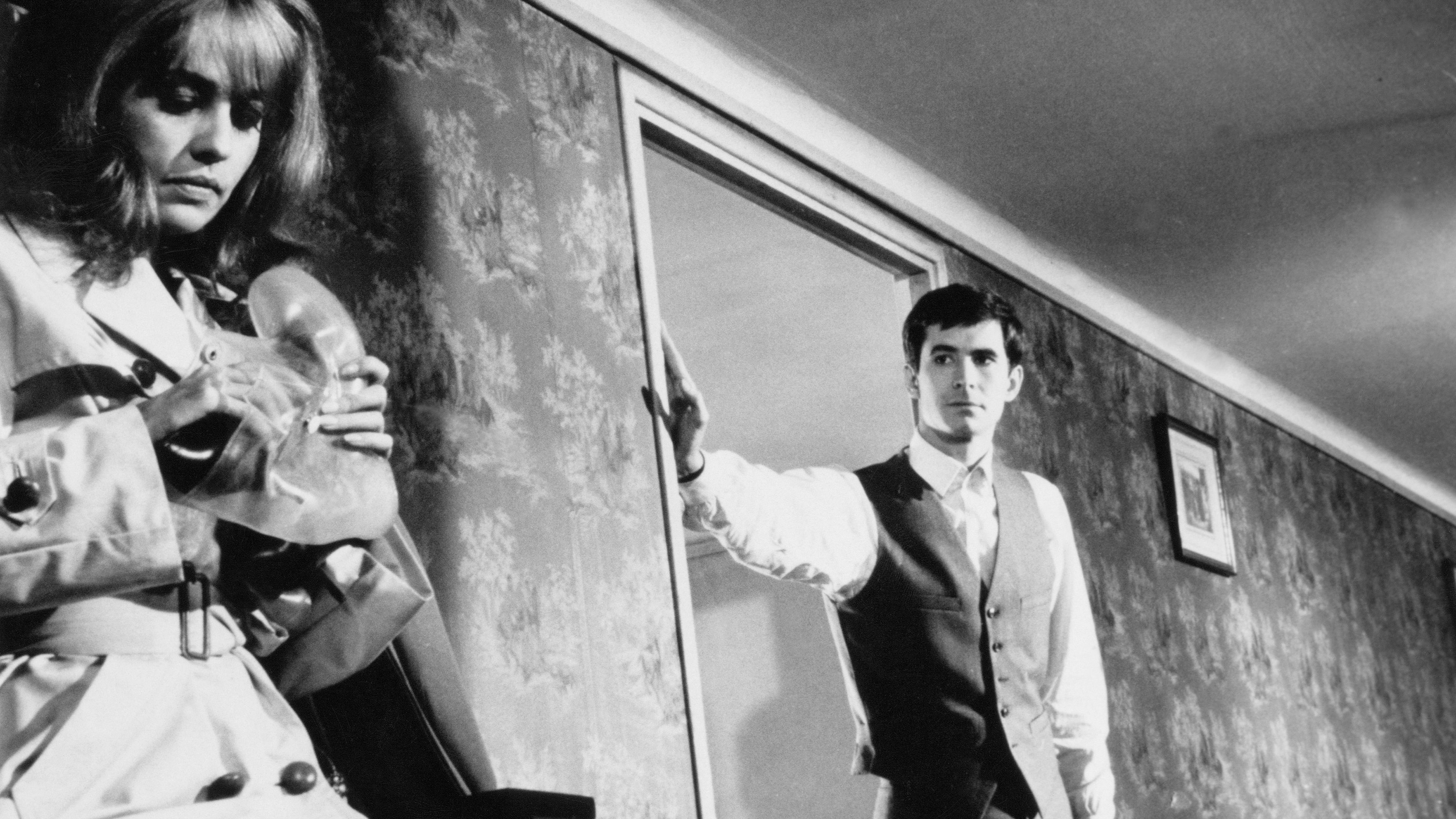

A heavyweight collaboration between Orson Welles and Franz Kafka; both known for their unique “Kafkaesque” and “Wellesian” styles. The result is everything you might expect and a lot you wouldn’t. Working in pristine black-and-white and with a decent budget, Welles delivers a searingly incisive version of Joseph K’s ludicrous battle with bureaucracy and a judicial system that never seems able to tell him why he is on trial. As the bewildered and disoriented K, Anthony Perkins gives one of the best performances of his career. Also with Jeanne Moreau and Orson Welles. Australian premiere of the new 4K restoration.

“The Trial plays closer to an actual nightmare than just about any film I’ve ever seen.” — Jeffrey M. Anderson

“Welles has created a visual tour-de-force that resembles no commercial films of the early sixties but rather the works of surrealists and experiment filmmakers.” — Danny Peary

The 3pm screening on Saturday 29 April will be introduced by Lynden Barber. Lynden Barber is a freelance film & music journalist; a curator for the National Film and Sound Archive website, Australian Screen Online; and lecturer in screen studies at Sydney Film School. He blogs at Eyes Wired Open.

4K RESTORATION

"Orson Welles's nightmarish, labyrinthine comedy of 1962 remains his creepiest and most disturbing work; it's also a lot more influential than most people admit." — Jonathan Rosenbaum

A heavyweight collaboration between Orson Welles and Franz Kafka; both known for their unique “Kafkaesque” and “Wellesian” styles. The result is everything you might expect and a lot you wouldn’t. Working in pristine black-and-white and with a decent budget, Welles delivers a searingly incisive version of Joseph K’s ludicrous battle with bureaucracy and a judicial system that never seems able to tell him why he is on trial. As the bewildered and disoriented K, Anthony Perkins gives one of the best performances of his career. Also with Jeanne Moreau and Orson Welles. Australian premiere of the new 4K restoration.

“The Trial plays closer to an actual nightmare than just about any film I’ve ever seen.” — Jeffrey M. Anderson

“Welles has created a visual tour-de-force that resembles no commercial films of the early sixties but rather the works of surrealists and experiment filmmakers.” — Danny Peary

The 3pm screening on Saturday 29 April will be introduced by Lynden Barber. Lynden Barber is a freelance film & music journalist; a curator for the National Film and Sound Archive website, Australian Screen Online; and lecturer in screen studies at Sydney Film School. He blogs at Eyes Wired Open.

FILM NOTES

By Adrian Danks

Orson Welles

Orson Welles’ (1915–1985) first feature, Citizen Kane (1941), is a critical juggernaut that has defined popular understandings of the larger-than-life writer, director, and actor’s peripatetic oeuvre. Yet Welles’ extremely rich and much travelled career goes far beyond this extraordinary but somewhat cold film classic. It spans 50 years, from the earnest but playful beginnings of the home movie-like The Hearts of Age (1934) to his final string of incomplete projects, diverse acting assignments, voiceover jobs, and droll, labyrinthine essay films: F for Fake (1973) and Filming ‘Othello’ (1978).

Many accounts of Welles’ work document the difficulties he faced in completing many of his subsequent projects – these legendary works include Don Quixote, The Deep, It’s All True, The Merchant of Venice, and the posthumously completed The Other Side of the Wind (2018) – but on closer inspection the twelve features he did finish during his lifetime provide a fascinating and detailed account of his thematic, artistic, and literary preoccupations. Welles’ career moves from Hollywood and peak studio production in the 1940s to Europe and the trials and tribulations of multinational, multi-partner, and multi-location filmmaking. His work is also dominated by adaptations of key writers including Booth Tarkington, William Shakespeare, Isak Dinesen, and Franz Kakfa. This penchant for adaptation was a skill that he honed during his incredibly productive early career in theatre and radio in 1930s, a shooting-star fame that led to an unprecedented invitation by RKO to make a film of his choice (though initial plans to adapt Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Dickens’ Pickwick Papers fell through). Welles’ second feature, the extraordinary The Magnificent Ambersons, was significantly cut and partly reshot against his wishes, and much of the rest of his career is characterised by a capacity to create composite works under difficult financial and physical conditions. In keeping with this, a number of his subsequent films, like Mr. Arkadin(Confidential Report, 1955) and Touch of Evil (1958), exist in multiple versions and document the collage-like approach he often took to his work.

Throughout his career Welles was obsessed with representations of power, exile, corruption, old age, the loss of innocence, performance, and illusion. Arguably at war with a filmmaking establishment that sought to contain him, Welles, ever the maverick, struggled to make films with the money he earned as an actor working on a mindbogglingly diverse slate of projects ranging from The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1949), Moby Dick (John Huston, 1956), and Ro.Go.Pa.G (1962, in the episode contributed by Pier Paolo Pasolini) to Napoleon (Sacha Guitry, 1955), Necromancy(Bert I. Gordon, 1972), and Butterfly (Matt Cimber, 1981). Nevertheless, freed from many restrictions, Welles managed to create a remarkably cohesive, if somewhat piecemeal body of work that consistently explored his favourite themes, and that, often through necessity, pushed the boundaries of filmmaking practice. As David Thomson has claimed, Welles’ “is the greatest career in film, the most tragic, and the one with the most warnings for this rest of us” (1). This is all true, but we need to fully celebrate what is there.

The Film

The indelible signature of Orson Welles has so dominated popular understandings of the filmmaker’s work that it is sometimes forgotten that he was a master of adaptation. This dominant aspect of his output dates from his extraordinarily productive work in theatre and radio in the second half of the 1930s and includes celebrated and much-discussed adaptations like his staging of a “voodoo” Macbeth for the Federal Theatre Project in 1936 and his infamousWar of the Worlds broadcast in 1938. This aspect of Welles’ work has been partly downplayed due to his characterisation as a wunderkind and inventor of forms who overwhelmingly occupied and dominated almost any project he took on. This has led to some commentators suggesting that Welles often directed himself and even wrote his own lines when acting in films such as Norman Foster’s Journey into Fear (1943) and Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949). But it has also impacted how Welles’ various adaptations have been received and recognised.

Welles’ career in the 1960s is dominated by three significant and fully sympathetic adaptations of the work of Franz Kafka (The Trial, 1962), William Shakespeare (Chimes at Midnight, 1966), and Isak Dinesen (The Immortal Story, 1968). The Trial is a very careful adaptation of Kafka’s nightmarish 1925 novel of everyday bureaucracy and the law. As in other connected Welles films like Chimes at Midnight, The Tragedy of Othello: The Moor of Venice (1952), and The Immortal Story there is some reorganisation and restaging of the adapted material as well as considerable condensation. There are even some significant changes of emphasis such as the greater sense of agency granted to the central character of Josef K., particularly in his final, though still hopeless moments. But, in essence, this is a true “collaboration” between these two giants of 20th century literature and cinema. Welles does update Kafka’s world to take in the increasing mechanisation, corporatisation, commercialisation, and even corruption of the contemporary world – and there are certainly moments where Welles’ more feverish and dialogue-heavy conception and characterisation seem more Shakespearean than Kafkaesque – but he still manages to recreate the clipped sparseness of Kafka’s claustrophobic interiors and dialogue alongside the inexorable “nightmare” logic that drives the narrative.

As Raymond Durgnat has suggested, Welles’s adaptation communicates a sense of the “paranoid baroque” while never settling into a consistent style or form (2). In some ways, it is a composite Welles film, drawing on the key stylistic and thematic markers of many of his earlier works. There are bravura scenes characterised by fast-paced montage and the expressive use of very minimal or found settings, and others that demonstrate Welles’ facility with deep space, distorting lenses and angles, and the long take. But rather than this creating an incoherent sense of space, time, place, and their relation to character, it helps illustrate Josef K.’s increasingly discombobulated and confused, but indignant state. This is supported by Anthony Perkins’ slightly off-centre performance in the central role. As Welles’ voiceover announces in the animated prologue, The Trial has “the logic of a dream or nightmare”. But this logic is also deeply familiar to anyone who has lived under the maddening and labyrinthine bureaucracy and everyday living of communism and capitalism and their various combinations. Kafka wrote The Trial between 1914 and 1915 and it was published, posthumously, in the mid-1920s. It speaks to the modernity of that era, particularly within a specific place like Prague and in relation to its Jewish population. But as with Welles’ film, the implications of its story and situations spread out much wider.

Welles is commonly discussed as a quintessentially American filmmaker. This is understandable considering his upbringing and the preoccupations of his initial features: Citizen Kane (1941), The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), The Stranger (1946), and The Lady from Shanghai (1947). His life and career are often examined in relation to overriding myths of success and failure as well as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s often-misunderstood claim that “there are no second acts in American lives”. This common career narrative positions Welles’ peak of success very early in his career – with his first feature, Citizen Kane – and considers everything else in its disappointed and dissipated wake. Welles’ subsequent career and even physical body are then perceived as ruins that sometimes coalesce or reform into brilliant but compromised artistic achievements such as Touch of Evil (1958) and the posthumously completedThe Other Side of the Wind (2018). In this regard, The Trial is exceptional. It is one of a number of films Welles made in Europe and that form a distinct and even dominant phase of his work. Most of these are adaptations of important works of European literature. The majority of these often wonderful, if piecemeal adaptations suffered because of a lack of physical and financial resources as well as their peripatetic shooting schedules. This would also lead to the failure to complete – at least during Welles’ lifetime – projects like Don Quixote and The Other Side of the Wind. The legend of these and other “unfinished” projects have also suggested the profligacy of Welles’ filmmaking processes and his careless misuse of other’s resources. But this view obscures the restless productivity of Welles in the wake of Citizen Kane and the extraordinary resourcefulness and creativity he brought to this often-itinerant filmmaking practice.

The Trial is unusual in Welles’ mid-career filmography as it is a project over which he maintained almost complete control. Although Welles was increasingly and understandably seen as a risky investment, this did not stop actors and producers wanting to work with him. The Trial was a project initiated by producers Alexander and Michael Salkind who had become acquainted with Welles during the making of Abel Gance’s The Battle of Austerlitz (1960). Welles was given the choice of over 80 public domain titles to adapt and felt that Kafka’s distinctive novel about corrupting power and the misuse of the law was a good match – although, to the producers’ chagrin, it turned out to not be in the public domain. Welles’ initial conception envisaged a more abstract adaptation that would gradually remove sets and props until K. was left stranded within a spatial and material void. It is easy see why this approach might have attracted Welles. Citizen Kane, for example, creates a prismatic portrait of its title character as a means of suggesting a terrifying hollowness at its centre.

But as I noted earlier, Welles was always an inventive, adaptive, and even pragmatic filmmaker. Although The Trial was budgeted at 650 million francs (around US$1.3 million) and featured several multinational stars including Anthony Perkins, Jeanne Moreau, Elsa Martinelli and Romy Schneider (the latter three in smaller roles), it still needed to cut corners to be completed on time and around budget. This is reflected in the various locations used across its ten-week shooting schedule. Commencing at the Studios de Boulogne in Paris on March 26, 1962, it also incorporated three weeks in Yugoslavia – most evident in the material shot in an exhibition hall outside Zagreb – filming in Rome, Milan, and Dubrovnik, and, most famously, in the cavernous spaces of the abandoned Gare d’Orsay. This might suggest a wasteful globetrotting production, but it more accurately reflects the collage aesthetic of Welles’ cinema and his practice of “making do” with the resources at hand. As in the earlier Othello, the material gathered for various scenes in the finished film often stretch across several locations, countries, and timeframes. These disparate elements are also sutured together by a post-synchronised soundtrack – noticeably synthetic in the many moments where the mouth movements of characters don’t follow the dialogue and Welles can be heard voicing of other actors – that brings together a collection of scenes, moments, spaces, and nationally diverse actors into what seems a coherent, if nightmarish world. This also helps grant the film and its situations a sense of timelessness and placelessness – while, at the same time, still very much reflecting when and where it was shot – appropriate to the material.

Nevertheless, one of the greatest achievements of The Trial is its palpable sense of space and place. Kafka’s novel feels very much a part of the environment he lived within. Even in the more forbidding and alienating spaces occupied by the legal authorities, the environment feels claustrophobic, labyrinthine, squalid. Welles recognises the impact of the subsequent 40 years of architectural modernity on the novel’s characters, but his choices are also pragmatic. Part of the reason he chose the Gare d’Orsay was because it was an available, evocative location that could be appropriated for the purposes of his film. This does not mean The Trial fails to draw on this location’s history or its symbolic or metaphorical implications. As Welles suggested, “I know this sounds terribly mystical, but really a railway station is a haunted place. And the story is all about people waiting, waiting, waiting for their papers to be filled. It is full of the hopelessness of the struggle against bureaucracy. Waiting for a paper to be filled is like waiting for a train, and it’s also a place [of] refugees. People were sent to Nazi prisons from there. Algerians were gathered there…” (3). This speaks to the deeper resonance that Welles was aiming to draw from his chosen locations. What is remarkable about The Trialare the ways it incorporates a spatial history of modernity from the modern office and apartment to the ruins of war, the ornate spectacle of the abandoned Beaux-Arts style of the Gare d’Orsay, and the squalor of the tenements. It even includes some moments and images that are reminiscent of the border town of Touch of Evil. The law officers who initially interrogate K. would seem more at home ransacking a motel room on the Mexican border than a sparse bedsit in an apartment block somewhere in middle Europe. Similarly, the interrogation/torture scenes involving these figures later in the film seem closer to an inventive no budget b-noir, in their use of just a single hanging light, a tightly enclosed space, and the suggestion of brutal violence, than the European art movie The Trial otherwise most resembles.

But the film’s other major achievement is how it manages to acutely position K. withinthis system and environment. In Perkins’ eager and productively out-of-place performance, K. comes across as both a victim and a perpetrator, a figure who is impossible to subtract from his surroundings and the system they help perpetuate. This is fully evident in the superior way that K. responds to his fellow, minion-like workers and the indignant manner with which he treats those closer to the law. K. isn’t so much against the system; he is a symptom of it. Welles’The Trial starts memorably with a parable, beautifully illustrated by the pinscreen animation of Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker, about a man waiting outside a door to be accepted into the “law”. He waits his whole life before being told that the door is only meant for him, realising it will be opened and closed at the moment of his death. This parable speaks to the labyrinthine nature of the law and the various “circles” one must journey through to approach its ever-distant centre. But it also, more profoundly, suggests that this figure is always already subject to and formed by the law – he is both outside and inside of it. This is a truly pessimistic worldview and communicates an overall lack of humour and sense of incessant doom in both Kafka’s book and Welles’ adaptation. Welles’ The Trial does have its moments of absurd, almost surreal humour, but it is ultimately, along with The Immortal Story, the filmmaker’s most sober and distanced film.

Welles has suggested that The Trial was his favourite of the films he completed. The finished film is certainly amongst the closest to his initial conception and vision. Its existence also questions the out-sized excesses often laid at the feet of Welles. Filming was completed very close to on-schedule in early June and, after several months of intense editing, The Trial received its French premiere on December 21, 1962, before debuting in New York in February the next year. It is an exhausting, demanding, and sometimes infuriating film – this is not a movie to seek out for strong or sympathetic female characters, for instance – but it did go onto significant commercial and critical success in several European countries including France. Although Andrew Sarris was very critical, calling it “the most hateful, the most repellent, and the most perverted film Welles ever made”, his criticisms speak of a lack of affinity for the material, Welles’ faithfulness to Kafka’s text, and his embrace of the chilly, European modernity of the novelist (4). My view of the film is closer to that of David Thomson. Although I’d fall short of calling it one of the “three masterpieces” Welles made in an eight-year run between Touch of Evil and Chimes at Midnight, it is a commanding and bravura work that “is pretty good Kafka as well as major Welles” (5). As I’ve outlined here, it is also a fascinatingly composite Welles film that casts a shadow across his entire career.

Endnotes:

1. David Thomson, The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, 4th ed., Little, Brown, London, 2002, p. 926.

2. Raymond Durgnat, Films and Feelings, Faber and Faber, London, 1967, p. 112.

3. Welles cited in Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, This is Orson Welles, ed. Jonathan Rosenbaum, HarperCollins, New York, 1992, p. 247.

4. Andrew Sarris, The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968, rev. ed., Da Capo Press, New York, 1996, p. 80.

5. David Thomson, ‘Have You Seen…?’: A Personal Introduction to 1,000 Films, Allen Lane, London, 2008, p. 914.

The Restoration

This restoration was

produced in 2022 by STUDIO CANAL and the Cinémathèque Française. The image and

sound restoration were done at the Immagine Ritrovata Laboratory (Paris-Bologna),

using the original 35mm negative. This project was supervised by STUDIO CANAL,

Sophie Boyer and Jean-Pierre Boiget. The restoration was funded thanks to the

patronage of Chanel.

Credits

Le procès | Director: Orson WELLES | France, USA,

Germany, Italy | 1962 | 119 mins | 4K Flat DCP (orig. 35mm, 1.37:1) | B&W |

Mono Sd. | English | (PG).

Production Companies: Paris-Europa Productions, Hisa-Film, Finanziaria Cinematografica Italiana (FICIT), Globus-Dubrava | Producers: Alexander SAKIND, Michael SALKIND, Enrico BOMBA | Script: Pierre CHOLOT, Orson WELLES, from Franz Kafka’s novel | Photography: Edmond RICHARD | Editors: Yonne MARTIN, Frederick MULLER, [Orson WELLES, uncredited] | Art Direction: Jean MANDAROUX | Sound: Jacques LEBRETON, Guy VILLETTE | Music: Jean LEDRUT | Costumes: [Helen THIBAULT, uncredited].

Cast: Anthony PERKINS (‘Josef K.’), Madeline ROBINSON (‘Mrs. Grubach’), Arnoldo FOÁ (‘Inspector A’), Orson WELLES (‘The Advocate’, Narrator), Jeanne MOREAU (‘Marika Burstner’), Suzanne FLON (‘Miss Pitti’), Romy Schneider (‘Leni’), Michael LONSDALE (‘Priest’), Akim TAMIROFF (‘Bloch’).

Production Companies: Paris-Europa Productions, Hisa-Film, Finanziaria Cinematografica Italiana (FICIT), Globus-Dubrava | Producers: Alexander SAKIND, Michael SALKIND, Enrico BOMBA | Script: Pierre CHOLOT, Orson WELLES, from Franz Kafka’s novel | Photography: Edmond RICHARD | Editors: Yonne MARTIN, Frederick MULLER, [Orson WELLES, uncredited] | Art Direction: Jean MANDAROUX | Sound: Jacques LEBRETON, Guy VILLETTE | Music: Jean LEDRUT | Costumes: [Helen THIBAULT, uncredited].

Cast: Anthony PERKINS (‘Josef K.’), Madeline ROBINSON (‘Mrs. Grubach’), Arnoldo FOÁ (‘Inspector A’), Orson WELLES (‘The Advocate’, Narrator), Jeanne MOREAU (‘Marika Burstner’), Suzanne FLON (‘Miss Pitti’), Romy Schneider (‘Leni’), Michael LONSDALE (‘Priest’), Akim TAMIROFF (‘Bloch’).