THE SACRIFICE (1986)

![]()

Randwick Ritz, Sydney:

7:00 PM

Thursday May 01*

8:10 PM

Monday May 05

Lido Cinemas, Melbourne:

7:00 PM

Thursday May 08*

3:00 PM

Monday May 12

*denotes session will include an introduction

Rating: MA15+

Duration: 149 minutes

Country: Sweden, France, UK

Language: Swedish, English, French with English subtitles

Cast: Erland Josephson, Susan Fleetwood, Johan Allan Edwall

Director: Andrei Tarkovsky

SYDNEY TICKETS ⟶

MELBOURNE TICKETS ⟶

7:00 PM

Thursday May 01*

8:10 PM

Monday May 05

Lido Cinemas, Melbourne:

7:00 PM

Thursday May 08*

3:00 PM

Monday May 12

*denotes session will include an introduction

Rating: MA15+

Duration: 149 minutes

Country: Sweden, France, UK

Language: Swedish, English, French with English subtitles

Cast: Erland Josephson, Susan Fleetwood, Johan Allan Edwall

Director: Andrei Tarkovsky

SYDNEY TICKETS ⟶

MELBOURNE TICKETS ⟶

4K RESTORATION – AUSTRALIAN PREMIERE

“…[W]hat you see in the frame is not limited to its visual depiction, but is a pointer to something stretching out beyond the frame to infinity; a pointer to life. Like the infinity of the image…a film is bigger than it is.” – Andrei Tarkovsky.

“Despite the lack of canonical consensus today as to which filmmakers should be counted as the true greats, one can make this claim about Tarkovsky because many active filmmakers today tell us as much.” – Nick James, Sight and Sound.

To conclude the complete retrospective of Tarkovsky’s feature films, screening from March through to May at the Ritz, Lido and Classic Cinemas, Cinema Reborn presents the swansong of a cinematic master and winner of the Grand Prix at Cannes, a fitting culmination to the director’s poetic-philosophical meditations via the medium of film.

Set against the backdrop of impending nuclear catastrophe, disillusioned actor-turned-critic Alexander (Erland Josephson) makes a desperate pact with God to sacrifice everything in his life in order to save the world.

The Sacrifice offers a poignant exploration of faith and finitude in transcendent Tarkovskyian style, with a sublime final sequence that is among the most notorious and revered in the history of film. An ecstatic experience, not to be missed.

Introduced by Richard James Allen at Ritz Cinemas and by David Heslin at Lido Cinemas

“…[W]hat you see in the frame is not limited to its visual depiction, but is a pointer to something stretching out beyond the frame to infinity; a pointer to life. Like the infinity of the image…a film is bigger than it is.” – Andrei Tarkovsky.

“Despite the lack of canonical consensus today as to which filmmakers should be counted as the true greats, one can make this claim about Tarkovsky because many active filmmakers today tell us as much.” – Nick James, Sight and Sound.

To conclude the complete retrospective of Tarkovsky’s feature films, screening from March through to May at the Ritz, Lido and Classic Cinemas, Cinema Reborn presents the swansong of a cinematic master and winner of the Grand Prix at Cannes, a fitting culmination to the director’s poetic-philosophical meditations via the medium of film.

Set against the backdrop of impending nuclear catastrophe, disillusioned actor-turned-critic Alexander (Erland Josephson) makes a desperate pact with God to sacrifice everything in his life in order to save the world.

The Sacrifice offers a poignant exploration of faith and finitude in transcendent Tarkovskyian style, with a sublime final sequence that is among the most notorious and revered in the history of film. An ecstatic experience, not to be missed.

Introduced by Richard James Allen at Ritz Cinemas and by David Heslin at Lido Cinemas

FILM NOTES

By Greg Dolgopolov

By Greg Dolgopolov

Greg Dolgopolov teaches at UNSW and curates a few film festivals.

ANDREI TARKOVSKY

Exiled Soviet auteur, Andrei Tarkovsky (1932-1986), is widely regarded as one of the greatest directors in world cinema. He directed seven feature films, a documentary, two shorts and wrote a further seven scripts on top of the ones that he wrote and directed. His debut long short, the charming and brilliantly vibrant, The Steamroller and the Violin (Katok i skripka, 1961), was radically different to his future films, with its celebration of the meeting between the intelligentsia and the proletariat, but it did feature a young boy experiencing a beautiful revelation. His first feature, Ivan's Childhood (Ivanovo detstvo, 1962), is a masterful evocation of the trauma of WWII from the point of view of a battle-hardened orphan boy who befriends three Soviet officers as he scouts behind enemy lines. The film won the Golden Lion at the 1962 Venice Film Festival and cemented Tarkovsky’s international reputation. He went on to direct several masterpieces, including Andrei Rublev (Andrey Rublyov, 1966), Solaris (1972), Mirror (Zerkalo, 1975), and Stalker (1979) in the Soviet Union. Although he was offered considerable State support for his work, which many others could only dream of, he became increasingly frustrated by official interference in his work and emigrated to Italy in the early 1980s. He completed the documentary, A Voyage in Time (Tempo di viaggio, 1983, co-directed by Tonino Guerra), and the drama, Nostalghia (Nostalgia, 1983), in Italy, and his final film, The Sacrifice (Offret, 1986), in Sweden.

He is known as a director who explored the most pressing themes of the twentieth century: alienation, disassociation, and the search for meaning in a seemingly cruel and brutally meaningless world. He is known as a religious director, as many of his films touch on faith and feature religious customs and a cinematic exploration of the soul. His films are characterised by spiritual and metaphysical themes, meditatively long takes and dream-like imagery. Over many films he has demonstrated a preoccupation with memory and the child’s view of the world, often surrounded by nature and flowing water.

Tarkovsky’s films won many of the most prestigious film awards. The Sacrifice won the Grand Prix at the 1986 Cannes Film Festival and he was nominated for the Palme d’Or three times and won the FIPRESCI prize three times.

Shortly after releasing The Sacrifice, he died of lung cancer in Paris at the age of 54. Tarkovsky's legacy as a visionary filmmaker endures. His works continue to be studied and admired for their profound artistic and spiritual depth and uncompromising commitment to his artistic vision.

He is known as a director who explored the most pressing themes of the twentieth century: alienation, disassociation, and the search for meaning in a seemingly cruel and brutally meaningless world. He is known as a religious director, as many of his films touch on faith and feature religious customs and a cinematic exploration of the soul. His films are characterised by spiritual and metaphysical themes, meditatively long takes and dream-like imagery. Over many films he has demonstrated a preoccupation with memory and the child’s view of the world, often surrounded by nature and flowing water.

Tarkovsky’s films won many of the most prestigious film awards. The Sacrifice won the Grand Prix at the 1986 Cannes Film Festival and he was nominated for the Palme d’Or three times and won the FIPRESCI prize three times.

Shortly after releasing The Sacrifice, he died of lung cancer in Paris at the age of 54. Tarkovsky's legacy as a visionary filmmaker endures. His works continue to be studied and admired for their profound artistic and spiritual depth and uncompromising commitment to his artistic vision.

THE FILM

The Sacrifice (1986), Andrei Tarkovsky's third and final film in exile, stands as a powerful testament to the director's enduring preoccupation with nature, spilt milk, rumbling silence, mute children, levitation, mysticism, spirituality and the long, long shot. This is a film about faith and hope and the (possibly) misguided belief that one person’s sacrifice can have a positive impact on others. It is a film worthy of watching and rewatching, as it is a parable that deserves discussion and reinterpretation, especially now that we are far closer to midnight on the Doomsday Clock than we were in 1986. And yet, the anxiety about an impending nuclear war seemed much higher then than now.

Tarkovsky has often been likened to Ingmar Bergman for his style and especially his religious preoccupations, and so this transcendent and deeply resonant creation is like a dark cinematic in-joke. The film was shot in Sweden, near Bergman’s home, on a softly-featured expanse of land that appears to melt into the surrounding water, with most of Bergman's long-time collaborators filling the crew roles and his most regular actor in the lead. Erland Josephson plays Alexander, a former actor and now a notable author who gathers his family and friends to celebrate his birthday in what becomes a rather maudlin affair, especially when they hear the TV news that nuclear war has broken out. The film's central premise, resonating with the Abraham-Isaac covenant, is that Alexander vows to God to sacrifice everything he loves – his house, his family, everything – in exchange for averting this global catastrophe. When he awakens the next day (after also performing a pagan ritual with a witch), Alexander finds that total destruction has been averted, and he blindly goes through with his pledge. The biblical echoes of Abraham's near sacrifice of Isaac are there, along with the pagan rituals of Andrei Rublev (1966), highlighting Tarkovsky’s deep engagement with religious themes and also leaving the film open to multiple interpretation. Has Alexander dreamt up all of this or is he mad? There is something of a dialogue here with the ideas of Winter Light (Ingmar Bergman, 1963) but, notwithstanding the overt scent of Bergman, this is a film that is resplendent with Tarkovsky’s style and symbolism.

The opening and closing scenes present a metaphysical expression of sacrifice as a seemingly meaningless act that drives us to an imaginative interpretation and, with a system of repetition, gives us hope. In a classic Tarkovskian long shot, Alexander is trying to plant a grotesquely withered tree by the water’s edge, as he tells his young son a story about an Orthodox monk who planted a barren tree on a mountainside. Ignoring the fact that the tree was dead, the young monk walked up the mountain and watered this tree every day. After three years the tree miraculously blossomed. This may be a parable for blind faith, for hope against hope, a sacrifice of time or gifting without an expectation of return. This film is about hope and about being ready to make a huge sacrifice for something that would be beneficial to all of humanity – not a selfish act. At the end of the film, we see the boy lying at the base of this raggedy tree by the water’s edge, looking up and questioning, ‘In the beginning was the Word. Why was that, Papa?’ The camera gently ascends into the tree's branches, leaving the viewer uncertain whether the tree is beginning to bloom or if it symbolises the spiky crown of thorns used to mock and torment Jesus, blurring the line between natural renewal and religious iconography.

The Sacrifice is a religious film with one of the greatest prayer sequences ever, but it is not dogmatic and its central thesis about the power of sacrifice calls for interpretations. In an often-cited interview, Tarkovsky says: ‘it's possible to interpret the film in different ways. For instance, those who are interested in various supernatural phenomena will search for the meaning of the film in the relationship between the postman and the witch; for them these two characters will provide the principal action. Believers are going to respond most sensitively to Alexander's prayer to God, and for them the whole film will develop around this. And finally, a third category of viewers who don't believe in anything will imagine that Alexander is a bit sick, that he's psychologically unbalanced as a result of war and fear. Consequently many kinds of viewers will perceive the film in their own way. My opinion is that it’s necessary to afford the spectator the freedom to interpret the film according to their own inner vision of the world, and not from the point of view that I would impose upon [them]. For my aim is to show life, to render an image, the tragic, dramatic image of the soul of modern man. In conclusion, can you imagine such a film being directed by a non-believer? I can't.’ (1)

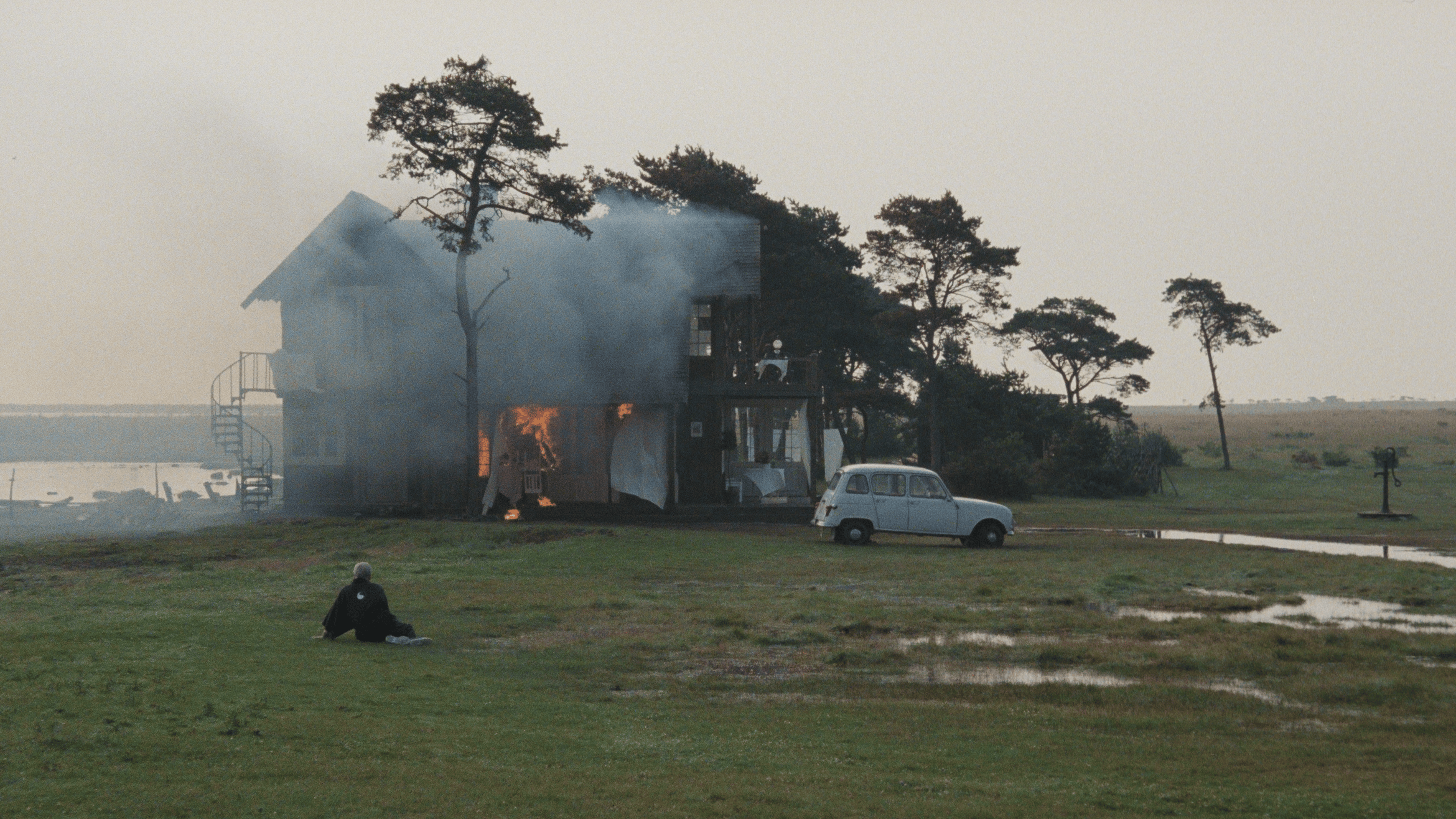

The Sacrifice is a parable about the power of faith and also of blind commitment to rituals and the transformative nature of sacrifice. Tarkovsky suggests that, through total faith and selfless action, humanity can find redemption and meaning in an increasingly materialist world but, unlike his earlier, more solemn films, here there is the possibility that these are just the dreams of an overly privileged narcissistic lunatic who sets fire to all that he possess in some sort of indulgent belief that his single actions can change an international catastrophe. The mute scene of Alexander running around the meadow while his house burns, followed by paramedics seeking to subdue him, is at once tragic and a comical escapade in the slapstick style of Keystone Cops.

One of the most remarkable stories about the production of this film is that this climactic sacrifice scene – the burning down of the house and car and all the family’s possessions, in a single six-minute take as a technical tour de force, not only showcased Tarkovsky’s mastery of the long take, but also his uncompromising stubbornness. In some ways he repeated the mistakes that he made with Stalker (1979), that required large sections of the film to be re-shot. Here, despite cinematographer Sven Nykvist's protest, only one camera was used on the tracks. It jammed halfway through the scene and could not be reloaded in time thereby failing to capture Alexander’s pathetic running around the meadow while being chased by his family and then the paramedics. The special effects explosions also didn’t work on this take. Rather than compromise, save public money, combine two shots and fix it in post, Tarkovsky blamed Nykvist and demanded that the scene needed to be reshot (2). This required an expensive rebuilding of the house in a short period of time, but that was only a small hiccup for a Soviet auteur with a history of unwavering artistic determination and demand for expensive reshoots. The allegory of the sacrifice was that Tarkovsky, as an uncompromising Soviet auteur, would never sacrifice his vision in the face of petty bourgeois parsimony.

Tarkovsky’s use of the dream sequence reached new heights in The Sacrifice. Alexander levitates after having been convinced to sleep with his family’s maid (who’s also a witch but ‘in the best possible sense’, according to his friend Otto, the postman and part-time philosopher in the best sense of the word). It is a moment that blurs the line between reality and the mystical and recalls similar ethereal moments in Stalker, Solaris and Mirror, reinforcing Tarkovsky’s fascination with the intersection of the physical and spiritual realms. The Sacrifice serves as a fitting capstone to Tarkovsky’s career, distilling many of his recurring themes and stylistic choices into a mature, powerful work. The film's exploration of faith and hope in the face of annihilation feels as relevant today as it did in the Cold War era of its release, speaking to the enduring relevance of Tarkovsky’s philosophical inquiries and his legacy as a visionary, tenacious Soviet auteur.

Notes:

Tarkovsky has often been likened to Ingmar Bergman for his style and especially his religious preoccupations, and so this transcendent and deeply resonant creation is like a dark cinematic in-joke. The film was shot in Sweden, near Bergman’s home, on a softly-featured expanse of land that appears to melt into the surrounding water, with most of Bergman's long-time collaborators filling the crew roles and his most regular actor in the lead. Erland Josephson plays Alexander, a former actor and now a notable author who gathers his family and friends to celebrate his birthday in what becomes a rather maudlin affair, especially when they hear the TV news that nuclear war has broken out. The film's central premise, resonating with the Abraham-Isaac covenant, is that Alexander vows to God to sacrifice everything he loves – his house, his family, everything – in exchange for averting this global catastrophe. When he awakens the next day (after also performing a pagan ritual with a witch), Alexander finds that total destruction has been averted, and he blindly goes through with his pledge. The biblical echoes of Abraham's near sacrifice of Isaac are there, along with the pagan rituals of Andrei Rublev (1966), highlighting Tarkovsky’s deep engagement with religious themes and also leaving the film open to multiple interpretation. Has Alexander dreamt up all of this or is he mad? There is something of a dialogue here with the ideas of Winter Light (Ingmar Bergman, 1963) but, notwithstanding the overt scent of Bergman, this is a film that is resplendent with Tarkovsky’s style and symbolism.

The opening and closing scenes present a metaphysical expression of sacrifice as a seemingly meaningless act that drives us to an imaginative interpretation and, with a system of repetition, gives us hope. In a classic Tarkovskian long shot, Alexander is trying to plant a grotesquely withered tree by the water’s edge, as he tells his young son a story about an Orthodox monk who planted a barren tree on a mountainside. Ignoring the fact that the tree was dead, the young monk walked up the mountain and watered this tree every day. After three years the tree miraculously blossomed. This may be a parable for blind faith, for hope against hope, a sacrifice of time or gifting without an expectation of return. This film is about hope and about being ready to make a huge sacrifice for something that would be beneficial to all of humanity – not a selfish act. At the end of the film, we see the boy lying at the base of this raggedy tree by the water’s edge, looking up and questioning, ‘In the beginning was the Word. Why was that, Papa?’ The camera gently ascends into the tree's branches, leaving the viewer uncertain whether the tree is beginning to bloom or if it symbolises the spiky crown of thorns used to mock and torment Jesus, blurring the line between natural renewal and religious iconography.

The Sacrifice is a religious film with one of the greatest prayer sequences ever, but it is not dogmatic and its central thesis about the power of sacrifice calls for interpretations. In an often-cited interview, Tarkovsky says: ‘it's possible to interpret the film in different ways. For instance, those who are interested in various supernatural phenomena will search for the meaning of the film in the relationship between the postman and the witch; for them these two characters will provide the principal action. Believers are going to respond most sensitively to Alexander's prayer to God, and for them the whole film will develop around this. And finally, a third category of viewers who don't believe in anything will imagine that Alexander is a bit sick, that he's psychologically unbalanced as a result of war and fear. Consequently many kinds of viewers will perceive the film in their own way. My opinion is that it’s necessary to afford the spectator the freedom to interpret the film according to their own inner vision of the world, and not from the point of view that I would impose upon [them]. For my aim is to show life, to render an image, the tragic, dramatic image of the soul of modern man. In conclusion, can you imagine such a film being directed by a non-believer? I can't.’ (1)

The Sacrifice is a parable about the power of faith and also of blind commitment to rituals and the transformative nature of sacrifice. Tarkovsky suggests that, through total faith and selfless action, humanity can find redemption and meaning in an increasingly materialist world but, unlike his earlier, more solemn films, here there is the possibility that these are just the dreams of an overly privileged narcissistic lunatic who sets fire to all that he possess in some sort of indulgent belief that his single actions can change an international catastrophe. The mute scene of Alexander running around the meadow while his house burns, followed by paramedics seeking to subdue him, is at once tragic and a comical escapade in the slapstick style of Keystone Cops.

One of the most remarkable stories about the production of this film is that this climactic sacrifice scene – the burning down of the house and car and all the family’s possessions, in a single six-minute take as a technical tour de force, not only showcased Tarkovsky’s mastery of the long take, but also his uncompromising stubbornness. In some ways he repeated the mistakes that he made with Stalker (1979), that required large sections of the film to be re-shot. Here, despite cinematographer Sven Nykvist's protest, only one camera was used on the tracks. It jammed halfway through the scene and could not be reloaded in time thereby failing to capture Alexander’s pathetic running around the meadow while being chased by his family and then the paramedics. The special effects explosions also didn’t work on this take. Rather than compromise, save public money, combine two shots and fix it in post, Tarkovsky blamed Nykvist and demanded that the scene needed to be reshot (2). This required an expensive rebuilding of the house in a short period of time, but that was only a small hiccup for a Soviet auteur with a history of unwavering artistic determination and demand for expensive reshoots. The allegory of the sacrifice was that Tarkovsky, as an uncompromising Soviet auteur, would never sacrifice his vision in the face of petty bourgeois parsimony.

Tarkovsky’s use of the dream sequence reached new heights in The Sacrifice. Alexander levitates after having been convinced to sleep with his family’s maid (who’s also a witch but ‘in the best possible sense’, according to his friend Otto, the postman and part-time philosopher in the best sense of the word). It is a moment that blurs the line between reality and the mystical and recalls similar ethereal moments in Stalker, Solaris and Mirror, reinforcing Tarkovsky’s fascination with the intersection of the physical and spiritual realms. The Sacrifice serves as a fitting capstone to Tarkovsky’s career, distilling many of his recurring themes and stylistic choices into a mature, powerful work. The film's exploration of faith and hope in the face of annihilation feels as relevant today as it did in the Cold War era of its release, speaking to the enduring relevance of Tarkovsky’s philosophical inquiries and his legacy as a visionary, tenacious Soviet auteur.

Notes:

- Charles H. de Brantes, ‘Faith is the Only Thing That Can Save Man’ (1986), from John Gianvito (ed.), Andrei Tarkovsky Interviews, University of Mississippi, Jackson, (2006), p. 179.

- ‘Diaries & Memoirs. Tarkovsky's Martyrolog on The Sacrifice.’ From the Polish edition of Martyrolog, ed. and trans. by Seweryn Kuśmierczyk. Retranslation by Jan at Nostalghia.com. [http://www.nostalghia.com/TheDiaries/sacrifice.html]

THE RESTORATION

Source: Park Circus, Australia

DCP Swedish Institute

Director: Andrei Tarkovsky; Production Companies: Swedish Film Institute, Faragó Film, Argos Films, British Film Institute, Josephson & Nykvist; Producer: Anna-Lena Wibom; Script: Andrei Tarkovsky; Photography: Sven Nykvist; Editors: Andrei Tarkovsky, Michal Leszczylowski; Production Design: Anna Asp; Costume Design: Inger Pehrsson; Music: Johann Sebastian Bach, Watazumi Doso

Cast: Erland Josephson (Alexander), Susan Fleetwood (Adelaide), Allan Edwall (Otto), Guðrún S. Gísladóttir (Maria), Sven Wolter (Victor)

Sweden/France/UK | 1986 | 149 mins | Colour | Swedish, English, French with English subtitles | MA (15+).

DCP Swedish Institute

Director: Andrei Tarkovsky; Production Companies: Swedish Film Institute, Faragó Film, Argos Films, British Film Institute, Josephson & Nykvist; Producer: Anna-Lena Wibom; Script: Andrei Tarkovsky; Photography: Sven Nykvist; Editors: Andrei Tarkovsky, Michal Leszczylowski; Production Design: Anna Asp; Costume Design: Inger Pehrsson; Music: Johann Sebastian Bach, Watazumi Doso

Cast: Erland Josephson (Alexander), Susan Fleetwood (Adelaide), Allan Edwall (Otto), Guðrún S. Gísladóttir (Maria), Sven Wolter (Victor)

Sweden/France/UK | 1986 | 149 mins | Colour | Swedish, English, French with English subtitles | MA (15+).