THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI (1947)

4:00 PM, Thursday April 28

6:00PM, Friday April 29

Randwick Ritz

Director: Orson Welles

Country: USA

Year: 1947

Runtime: 87 minutes

Rating: PG

Language: English, Cantonese.

TICKETS ⟶

6:00PM, Friday April 29

Randwick Ritz

Director: Orson Welles

Country: USA

Year: 1947

Runtime: 87 minutes

Rating: PG

Language: English, Cantonese.

TICKETS ⟶

“AS TANGLED AND INGENIOUS AS ANY OF WELLES’S CONJURING TRICKS” – THE INDEPENDENT (UK)

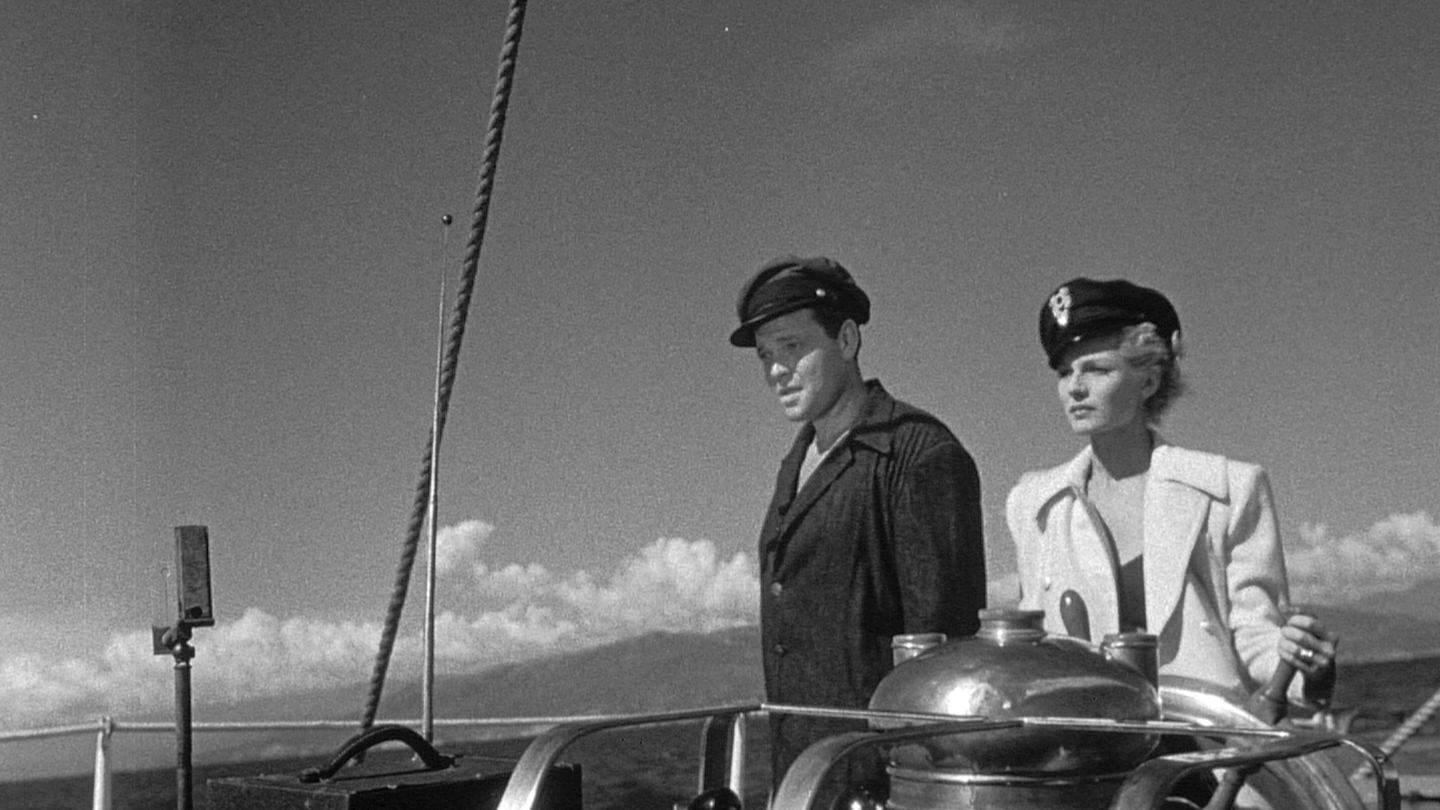

Orson Welles takes on film noir with this story of murder, fraud, deceit, betrayal and, of course, a femme fatale.

Travelling from New York, to a yacht on route through the Caribbean to Acapulco, up to San Francisco’s Chinatown and finally into a playground amusement park, Welles plays an Irish seaman drawn into this noir chaos by a mysterious woman (Rita Hayworth).

“Like most of Welles’ Hollywood efforts, Shanghai was shanghaied by studio tampering…but it also contains some of his greatest set pieces, topped by the delirious shootout in the funhouse hall of mirrors.”– Boulder Weekly

“One intriguing reading of the movie is that it’s a commentary on Welles’s marriage to Hayworth…Complex, courageous and utterly compelling.” – Martyn Auty, Time Out Film Guide

Orson Welles takes on film noir with this story of murder, fraud, deceit, betrayal and, of course, a femme fatale.

Travelling from New York, to a yacht on route through the Caribbean to Acapulco, up to San Francisco’s Chinatown and finally into a playground amusement park, Welles plays an Irish seaman drawn into this noir chaos by a mysterious woman (Rita Hayworth).

“Like most of Welles’ Hollywood efforts, Shanghai was shanghaied by studio tampering…but it also contains some of his greatest set pieces, topped by the delirious shootout in the funhouse hall of mirrors.”– Boulder Weekly

“One intriguing reading of the movie is that it’s a commentary on Welles’s marriage to Hayworth…Complex, courageous and utterly compelling.” – Martyn Auty, Time Out Film Guide

FILM NOTES

By David Hare

Orson Welles:

Fate was not

looking kindly upon Orson Welles when his 155 minute rough cut of The Magnificent Ambersons was rejected by a new, hostile management at RKO in 1942. A substantial recut to 131 minutes was made by Welles

working with house director Robert Wise to reduce the picture to a more

commercially friendly length which finally ended up out of Welles’ hands at a modest 88 minutes on

release. A further ignominy was the

removal of almost all of Bernard Herrmann’s score for the picture, obliging the

composer to remove his name from the credits.

Three years later, in a hideous recapitulation of this affair, Welles was experiencing another one of his career purgatories, the turkey that became “Around the World in 80 Days”. He had previously acted in and silently directed part of a tight RKO “B” thriller, Journey into Fear in 1943. The picture was successful enough to keep Welles in RKO’s good books to direct another post war Nazi undercover “A” picture, The Stranger in 1945 with Welles in the eponymous role playing a Nazi escapee, supported by a solid cast including Loretta Young - surprisingly restrained under Welles’ direction - and Edward G. Robinson. But with the total flop of his mega roadshow junket, “Around the World ….” in ‘45 he was broke and in major debt to several contributors including Cole Porter whose score, it has to be said, might be the worst thing he ever wrote.

It wasn’t actually Welles himself later in 1945 who first pitched the deal to Harry Cohn to make The Lady from Shanghai at Columbia, but in fact William Castle, a pal of Welles, a young hotshot doing the rounds of the writing desks at various studios, most lately Cohn’s where he had sniffed out Sherwood King’s original novel and won over Cohn who agreed to take on Welles as star and director.

As Welles’ best biographer, Simon Callow says, he was a perpetual flirt – men, women - and he could charm the pants off a rhino, including one as tough as Harry Cohn. So he did just that securing a two million dollar budget for The Lady from Shanghai, as a vehicle for Columbia’s biggest star, Rita Hayworth whom in another unbelievable stroke of fate, Welles had married two years earlier but from whom he was now in the process of a protracted but amicable separation and divorce.

With no acrimony between them to muddy the waters, a Hayworth picture with a budget like this was something Welles couldn’t pass. And his bold conception for the screenplay was in many ways a rebirthing of the doomed “Around the World” idea from 1945 in which the globe, or at least the North American part of it is encircled by a boat called “Zaca” - no less than Errol Flynn’s own yacht on loan to travel from New York south to Mexico and Acapulco, then along the West to San Francisco and Sausalito where the picture ends.

Already bitten by a life-long travel bug, Welles savored the flavors of location shooting with newly improved faster film stock and wide angle lenses for quick filming and a nascent kind of post war open air “realism”, a direction he was largely pioneering at this point in American movies in 1946.

Contrary to so much false mythology about Welles’ “profligacy” he began shooting The Lady from Shanghai in mid 1946 and delivered the finished picture late that year in its 155 minute rough cut – the same duration as his earlier rough cut of Ambersons. He had come in within time and under the two million budget. Then the fireworks began and fate again drew storm clouds over another Welles project.

Three years later, in a hideous recapitulation of this affair, Welles was experiencing another one of his career purgatories, the turkey that became “Around the World in 80 Days”. He had previously acted in and silently directed part of a tight RKO “B” thriller, Journey into Fear in 1943. The picture was successful enough to keep Welles in RKO’s good books to direct another post war Nazi undercover “A” picture, The Stranger in 1945 with Welles in the eponymous role playing a Nazi escapee, supported by a solid cast including Loretta Young - surprisingly restrained under Welles’ direction - and Edward G. Robinson. But with the total flop of his mega roadshow junket, “Around the World ….” in ‘45 he was broke and in major debt to several contributors including Cole Porter whose score, it has to be said, might be the worst thing he ever wrote.

It wasn’t actually Welles himself later in 1945 who first pitched the deal to Harry Cohn to make The Lady from Shanghai at Columbia, but in fact William Castle, a pal of Welles, a young hotshot doing the rounds of the writing desks at various studios, most lately Cohn’s where he had sniffed out Sherwood King’s original novel and won over Cohn who agreed to take on Welles as star and director.

As Welles’ best biographer, Simon Callow says, he was a perpetual flirt – men, women - and he could charm the pants off a rhino, including one as tough as Harry Cohn. So he did just that securing a two million dollar budget for The Lady from Shanghai, as a vehicle for Columbia’s biggest star, Rita Hayworth whom in another unbelievable stroke of fate, Welles had married two years earlier but from whom he was now in the process of a protracted but amicable separation and divorce.

With no acrimony between them to muddy the waters, a Hayworth picture with a budget like this was something Welles couldn’t pass. And his bold conception for the screenplay was in many ways a rebirthing of the doomed “Around the World” idea from 1945 in which the globe, or at least the North American part of it is encircled by a boat called “Zaca” - no less than Errol Flynn’s own yacht on loan to travel from New York south to Mexico and Acapulco, then along the West to San Francisco and Sausalito where the picture ends.

Already bitten by a life-long travel bug, Welles savored the flavors of location shooting with newly improved faster film stock and wide angle lenses for quick filming and a nascent kind of post war open air “realism”, a direction he was largely pioneering at this point in American movies in 1946.

Contrary to so much false mythology about Welles’ “profligacy” he began shooting The Lady from Shanghai in mid 1946 and delivered the finished picture late that year in its 155 minute rough cut – the same duration as his earlier rough cut of Ambersons. He had come in within time and under the two million budget. Then the fireworks began and fate again drew storm clouds over another Welles project.

The Film:

Harry Cohn hated

the rough cut and fought Welles on a number of things, among them Welles’ preference

for long takes over the big studio glamour close-ups and comprehensive editing,

anathema for Welles’s dislike of high volume cutting and montage. Like Ford, his “guru”, Welles favored

travelling shots and movement against concentrated editing, and also like Ford,

he used character introductions in vignette form to get the narrative and

things like “plot” running without lengthy expositions which, again like Ford,

he hated. His great, long open air takes

were the first things to succumb to editor Viola Lawrence’s scissors when Cohn

ordered her to turn it into a playable 90 minutes. To cover so much missing

material Welles was then obliged to take on an expensive post-production overrun

and bring back actors for reshoots staged with routine over-the-shoulder reverse/shots

for dialogue with the location backgrounds previously filmed now laid onto matte

process shots via very costly lab work. The costs for this alone blew the final

budget out by 10%.

They also fought over the music score. Cohn insisted on a tepid theme song for the credits, “Please Don’t Kiss Me” and bog common monothematic cue scoring from Columbia’s regular composer, Heinz Roemheld. This was recorded as Rita’s only musical number on the boat before they land in Acapulco, and as usual her voice double, Anita Ellis sings it. Mercifully the finished cut trims it to a lone verse, less than a minute, and Welles, having to address Cohn’s insistence on the big glamour close ups of Rita throughout, subverts and parodies the whole trope of Hollywood “Star” moments by staging and lighting it in the style of an Eisensteinian Potemkin-style montage, cutting to supersized overhead close ups of Rita at a diagonal against the wide shots of the three men on deck, each positioned in asymmetrical visual relation to each other, staring obliquely beyond the frame into god knows what mystery. So the sequence itself becomes both a routine studio “Stop for the music” point for Rita’s fans, and a wicked satire on the apparatus of star technique. It works brilliantly both as satire and in final context, just as everything else in the film works so well, even in the final Viola Lawrence 88 minutes cut, once again, thanks to the furies, exactly the same duration as the final edited time of the release print of Ambersons.

Welles had planned some adventurous, diegetic native music scoring and jungle soundscape for the Brazilian sequences and some of that remains in the slow Rhumba rhythm for the dusk bayside scene in which the three men drunkenly exchange aphorisms about such Wellesian conceits as Scorpions and Frogs in place of routine transitional dialogue. What becomes clear from this and many other sequences, even after the episode was reduced from over 30 minutes to ten, is the totally corrupt character of these awful people with whom Michael O’Hara has now found himself trapped as a plaything.

Viola Lawrence cut yet more long tracking shots of O’Hara and Grisby walking up the hill at Acapulco in Magic Hour (only the beginning of one of these shots still survives) during which George Grisby discloses his nuclear war paranoia and unfolds a convoluted escape plan to the guileless Michael. Grisby is played by the astonishing Glenn Anders - some may remember him from Harry d’Addabie d’Arrast’s early talkie, Laughter(1931) - who reads his lines in a voice that seems to cross Howard Keel’s baritone with Franklin Pangborn’s vocal mince. His character, frankly everyone’s character in this movie, is up for grabs. Anders’ performance is literally indescribable, brave, mad and completely off the boards.

It’s clear by now Welles has landed us in a post-war atmosphere of entropy and the brilliance of The Lady from Shanghai, against all odds, is to play off this small tragedy of a likeable fall guy in a world out of his or anyone’s moral compass using the sharpest forms of satire through characterization and extreme stylization. Welles’ very dark humor is always there, untouchable, even finally by Cohn and his editor.

A completely brilliant pre-trial scene is played at the Golden Gate Park Aquarium, when Michael secretly meets Elsa. She unveils another plot to double cross Grisby’s own plot, and they are observed initially by a rowdy group of children out on an excursion. Welles goes for broke with the lab work again and pulls in the big close up mechanics, again to extremis, moving the furtive lovers away from the others, deeper into super-sized close-ups to the point where only bits of their faces in almost full shadow can barely be contained by the sides of the frame. In the space between them we can now only see the aquatic creatures in a series of astonishing process zoom shots which with each cut keep enlarging the fish and eels finally to monstrous dimensions engulfing Elsa and Michael and the frame itself. Thus a completely throwaway transitional scene in the screenplay becomes a bravura visual correlative for the Acapulco prediction of prehistoric life taking over the earth.

Welles serves up a last act of unrestrained expressionism with the climactic awakening and shoot out in the “Fun House”, a deserted Fair on San Francisco’s North Beach following an earlier bobby dazzler of a sequence shot in that city’s ChInatown Mandarin Theatre near Portsmouth Square during a full blown live Chinese Opera performance. The fun house material took a big slab of Welles’ budget and time to build and shoot. It too became a casualty of Viola Lawrence’s shears although it still plays superbly in the current length. The Fun House opens with Michael still in a semi-narcotic stupor after his courtroom escape, leading him into a series of nightmarish terrifying fair rides which clearly salute the Weimar cinema of Dr.Caligari For the next ten minutes – originally more than twenty - Welles constructed a series of oversized phantasmagorical rides and traps and halls of mirrors, more than half of which were removed from the long cut. But this sequence resonates with terrific power, and it remains surely a testament to Welles’ ability to make every shot of the longer movie he originally filmed so organically connected to every other shot in the film that remains today so it still makes sense. Even a massive studio hatchet job like Columbia’s still can’t damage the final coherence or integrity of the movie or its mise-en-scène.

The trial as Welles shot it is almost completely intact, with a few obvious post-production cutaways for the Chinese pressroom staff back room with painted flats for office window views that look like Pacific Heights in the absence of even more expensive lab shots for the Court of Justice location. The trial is populated by an obviously dumbly willful judge, and an audience of Hogarthian spectators who cheer on Bannister’s stunts to land a murder on Michael which he didn’t commit. Bannister the mastermind, it should be mentioned at this point is played with perhaps the cinema’s greatest stage limp by Welles’ Mercury Theater alumnus, Everett Sloane, with exemplary malevolence. The crowd and the feckless judge are so out of control it’s almost like a recapitulation of the menacing wildlife in the jungle accompanying the travelers on their first Mexican stop. Such is Welles’ view of a world beginning its dystopian descent. In any case, it’s really impossible to imagine what sort of pacing, mood, tone, and impact a much longer version would have really played.

As it stands I think The Lady from Shanghai remains a Welles masterpiece, despite every ignominy visited upon it by a studio system with which he had so much trouble, but one thanks to which he produced so much of genius.

The next picture Welles would make in 1948 was a superb adaptation of Macbethfor Republic PIctures, with a tight budget , even for that resourceful outfit, of $700,000 and a 23 day shoot, all on a sound stage using existing props, flats and bits of sets and discarded costumes from Republic western serials. The movie is an outstanding work of filmed Shakespeare and a central Welles picture. Amongst all the niceties and all the fine dramatic strokes Welles applies to Shakespeare’s text, one that usually goes unnoticed is the addition of a silent character who doesn’t even exist in the play at all. He’s a “Holy Father” played with strong clear overhead lighting by Alan Napier who takes his marks during the action without ever intervening in it, like a mute witness to appeal to some vague possibility of good in a world that otherwise seems to have gone to hell.

They also fought over the music score. Cohn insisted on a tepid theme song for the credits, “Please Don’t Kiss Me” and bog common monothematic cue scoring from Columbia’s regular composer, Heinz Roemheld. This was recorded as Rita’s only musical number on the boat before they land in Acapulco, and as usual her voice double, Anita Ellis sings it. Mercifully the finished cut trims it to a lone verse, less than a minute, and Welles, having to address Cohn’s insistence on the big glamour close ups of Rita throughout, subverts and parodies the whole trope of Hollywood “Star” moments by staging and lighting it in the style of an Eisensteinian Potemkin-style montage, cutting to supersized overhead close ups of Rita at a diagonal against the wide shots of the three men on deck, each positioned in asymmetrical visual relation to each other, staring obliquely beyond the frame into god knows what mystery. So the sequence itself becomes both a routine studio “Stop for the music” point for Rita’s fans, and a wicked satire on the apparatus of star technique. It works brilliantly both as satire and in final context, just as everything else in the film works so well, even in the final Viola Lawrence 88 minutes cut, once again, thanks to the furies, exactly the same duration as the final edited time of the release print of Ambersons.

Welles had planned some adventurous, diegetic native music scoring and jungle soundscape for the Brazilian sequences and some of that remains in the slow Rhumba rhythm for the dusk bayside scene in which the three men drunkenly exchange aphorisms about such Wellesian conceits as Scorpions and Frogs in place of routine transitional dialogue. What becomes clear from this and many other sequences, even after the episode was reduced from over 30 minutes to ten, is the totally corrupt character of these awful people with whom Michael O’Hara has now found himself trapped as a plaything.

Viola Lawrence cut yet more long tracking shots of O’Hara and Grisby walking up the hill at Acapulco in Magic Hour (only the beginning of one of these shots still survives) during which George Grisby discloses his nuclear war paranoia and unfolds a convoluted escape plan to the guileless Michael. Grisby is played by the astonishing Glenn Anders - some may remember him from Harry d’Addabie d’Arrast’s early talkie, Laughter(1931) - who reads his lines in a voice that seems to cross Howard Keel’s baritone with Franklin Pangborn’s vocal mince. His character, frankly everyone’s character in this movie, is up for grabs. Anders’ performance is literally indescribable, brave, mad and completely off the boards.

It’s clear by now Welles has landed us in a post-war atmosphere of entropy and the brilliance of The Lady from Shanghai, against all odds, is to play off this small tragedy of a likeable fall guy in a world out of his or anyone’s moral compass using the sharpest forms of satire through characterization and extreme stylization. Welles’ very dark humor is always there, untouchable, even finally by Cohn and his editor.

A completely brilliant pre-trial scene is played at the Golden Gate Park Aquarium, when Michael secretly meets Elsa. She unveils another plot to double cross Grisby’s own plot, and they are observed initially by a rowdy group of children out on an excursion. Welles goes for broke with the lab work again and pulls in the big close up mechanics, again to extremis, moving the furtive lovers away from the others, deeper into super-sized close-ups to the point where only bits of their faces in almost full shadow can barely be contained by the sides of the frame. In the space between them we can now only see the aquatic creatures in a series of astonishing process zoom shots which with each cut keep enlarging the fish and eels finally to monstrous dimensions engulfing Elsa and Michael and the frame itself. Thus a completely throwaway transitional scene in the screenplay becomes a bravura visual correlative for the Acapulco prediction of prehistoric life taking over the earth.

Welles serves up a last act of unrestrained expressionism with the climactic awakening and shoot out in the “Fun House”, a deserted Fair on San Francisco’s North Beach following an earlier bobby dazzler of a sequence shot in that city’s ChInatown Mandarin Theatre near Portsmouth Square during a full blown live Chinese Opera performance. The fun house material took a big slab of Welles’ budget and time to build and shoot. It too became a casualty of Viola Lawrence’s shears although it still plays superbly in the current length. The Fun House opens with Michael still in a semi-narcotic stupor after his courtroom escape, leading him into a series of nightmarish terrifying fair rides which clearly salute the Weimar cinema of Dr.Caligari For the next ten minutes – originally more than twenty - Welles constructed a series of oversized phantasmagorical rides and traps and halls of mirrors, more than half of which were removed from the long cut. But this sequence resonates with terrific power, and it remains surely a testament to Welles’ ability to make every shot of the longer movie he originally filmed so organically connected to every other shot in the film that remains today so it still makes sense. Even a massive studio hatchet job like Columbia’s still can’t damage the final coherence or integrity of the movie or its mise-en-scène.

The trial as Welles shot it is almost completely intact, with a few obvious post-production cutaways for the Chinese pressroom staff back room with painted flats for office window views that look like Pacific Heights in the absence of even more expensive lab shots for the Court of Justice location. The trial is populated by an obviously dumbly willful judge, and an audience of Hogarthian spectators who cheer on Bannister’s stunts to land a murder on Michael which he didn’t commit. Bannister the mastermind, it should be mentioned at this point is played with perhaps the cinema’s greatest stage limp by Welles’ Mercury Theater alumnus, Everett Sloane, with exemplary malevolence. The crowd and the feckless judge are so out of control it’s almost like a recapitulation of the menacing wildlife in the jungle accompanying the travelers on their first Mexican stop. Such is Welles’ view of a world beginning its dystopian descent. In any case, it’s really impossible to imagine what sort of pacing, mood, tone, and impact a much longer version would have really played.

As it stands I think The Lady from Shanghai remains a Welles masterpiece, despite every ignominy visited upon it by a studio system with which he had so much trouble, but one thanks to which he produced so much of genius.

The next picture Welles would make in 1948 was a superb adaptation of Macbethfor Republic PIctures, with a tight budget , even for that resourceful outfit, of $700,000 and a 23 day shoot, all on a sound stage using existing props, flats and bits of sets and discarded costumes from Republic western serials. The movie is an outstanding work of filmed Shakespeare and a central Welles picture. Amongst all the niceties and all the fine dramatic strokes Welles applies to Shakespeare’s text, one that usually goes unnoticed is the addition of a silent character who doesn’t even exist in the play at all. He’s a “Holy Father” played with strong clear overhead lighting by Alan Napier who takes his marks during the action without ever intervening in it, like a mute witness to appeal to some vague possibility of good in a world that otherwise seems to have gone to hell.

The Restoration:

The film was restored in 4K

at Colorworks at Sony Pictures. The original nitrate negative was

scanned at 4K at Deluxe in Hollywood. Digital image restoration to

correct for damage was completed at MTI Film in Los Angeles, and audio

restoration at Chace Audio by Deluxe. Color correction and DCP completed

at Colorworks.

Credits:

Dir: Orson WELLES (uncredited) | USA | 1947 | 87 mins | 4K DCP (orig. 35mm) | B&W | 1.37:1 | Mono Sound | English, Cantonese | (PG).

Production Companies: Mercury Productions, Columbia Pictures| Producer: Orson WELLES | Script: Orson WELLES, (William CASTLE, Charles LEDERER, Fletcher MARKLE, uncredited), from Sherwood King’s novel If I Die Before I Wake | Photography: Charles LAWTON Jr. (Rudolph MATÉ, Joseph WALKER, uncredited) | Editor: Viola LAWRENCE| Art Direction: Sturges CARNE, Stephen GOOSSÓN | Sound: Lodge CUNNINGHAM| Music: Heinz ROEMHELD | Costumes: Jean LOUIS.

Cast: Rita HAYWORTH (‘Elsa Bannister’), Orson WELLES (‘Michael O’Hara’), Everett SLOANE (‘Arthur Bannister’), Glenn ANDERS (‘George Grisby’), Ted DE CORSA (‘Sidney Broome’), Erskine SANFORD (‘Judge’), Errol FLYNN (‘Man Outside of Cantina’, uncredited).

Source: Park Circus.

Credits:

Dir: Orson WELLES (uncredited) | USA | 1947 | 87 mins | 4K DCP (orig. 35mm) | B&W | 1.37:1 | Mono Sound | English, Cantonese | (PG).

Production Companies: Mercury Productions, Columbia Pictures| Producer: Orson WELLES | Script: Orson WELLES, (William CASTLE, Charles LEDERER, Fletcher MARKLE, uncredited), from Sherwood King’s novel If I Die Before I Wake | Photography: Charles LAWTON Jr. (Rudolph MATÉ, Joseph WALKER, uncredited) | Editor: Viola LAWRENCE| Art Direction: Sturges CARNE, Stephen GOOSSÓN | Sound: Lodge CUNNINGHAM| Music: Heinz ROEMHELD | Costumes: Jean LOUIS.

Cast: Rita HAYWORTH (‘Elsa Bannister’), Orson WELLES (‘Michael O’Hara’), Everett SLOANE (‘Arthur Bannister’), Glenn ANDERS (‘George Grisby’), Ted DE CORSA (‘Sidney Broome’), Erskine SANFORD (‘Judge’), Errol FLYNN (‘Man Outside of Cantina’, uncredited).

Source: Park Circus.