THE GODDESS 神女 (1934)

3:15 PM, Saturday April 30

Introduced by Susan Potter

Randwick Ritz

Director: WÚ Yǒnggāng

Country: China

Year: 1934

Runtime: 85 minutes

Rating: UC15+

Silent, with pre-recorded musical accompaniment

Language: Traditional Chinese intertitles/ English subtitles

TICKETS ⟶

Introduced by Susan Potter

Randwick Ritz

Director: WÚ Yǒnggāng

Country: China

Year: 1934

Runtime: 85 minutes

Rating: UC15+

Silent, with pre-recorded musical accompaniment

Language: Traditional Chinese intertitles/ English subtitles

TICKETS ⟶

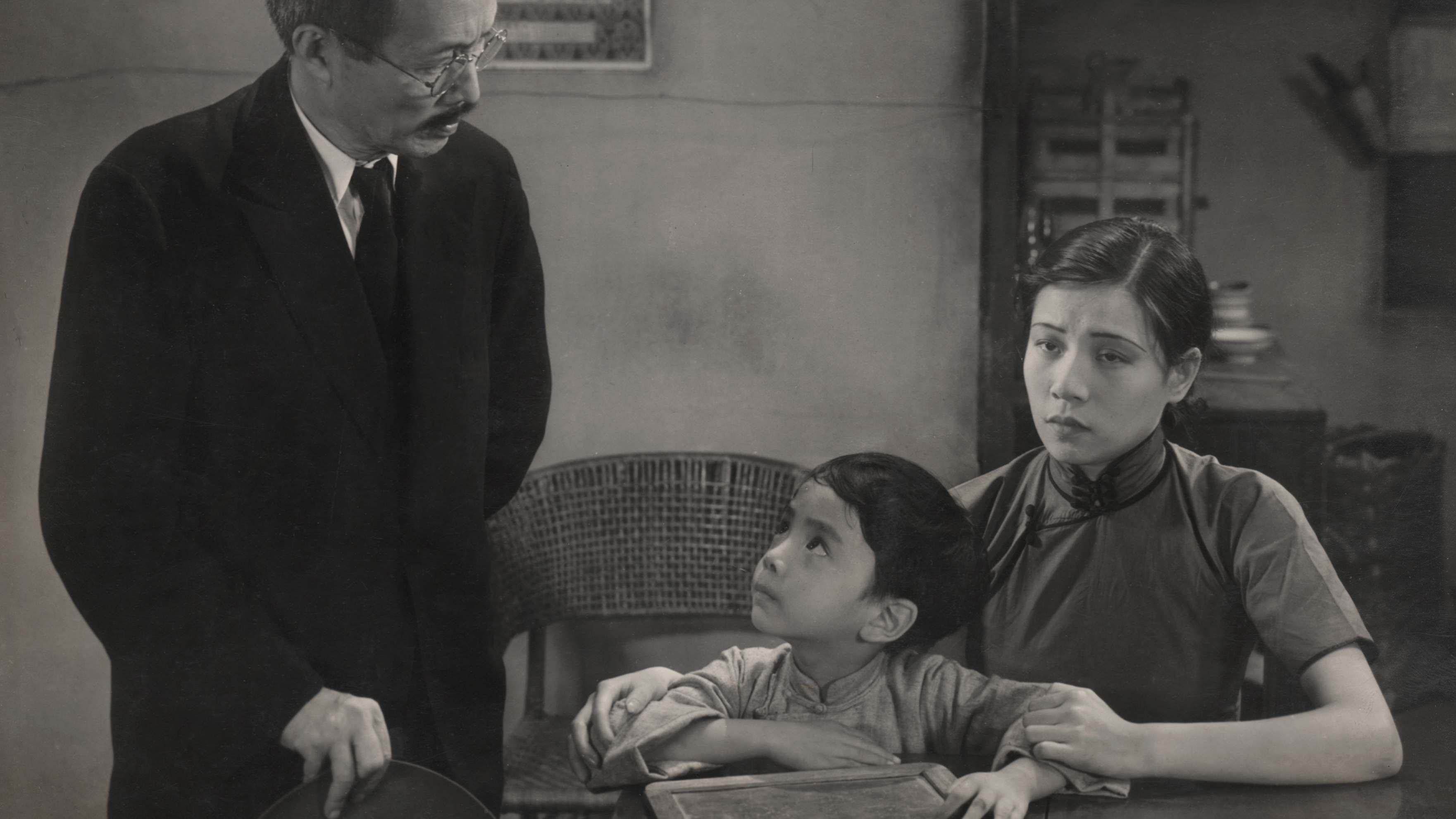

“ONE OF THE MOST POWERFUL SILENT FILMS OF ALL TIME” – SIGHT AND SOUND

Set in Shanghai, an unnamed woman must take up prostitution in order to support her son. Avoiding detection from the police, she accepts the protection of a criminal boss whose habitual gambling and violent personality end up causing her further problems.

The legendary Ruan Lingyu, sometimes called the Greta Garbo of Chinese cinema, was the biggest star in Shanghai cinema during the 1930s and here, produces a luminous performance as the mother forced into prostitution.

“Ruan’s performance is so heartrendingly pure that the film is almost unbearable to watch…this great performer lends weight to the argument the purest films came out in the silent era.” – Jeffrey M Anderson

“The kind of film that demands a rewriting of the film history books…Free of moralism and melodrama, expressively composed and lit and very naturalistically acted, this is a film of startling modernity.” – Tony Rayns, Time Out Film Guide

Introduced by Susan Potter, Senior Lecturer in Film Studies, Department of Art History, University of Sydney.

Watch the Original 1934 Trailer

FILM NOTES

By Janice Tong

WÚ Yǒnggāng

:

Hailed as one of the greatest films of

Early Chinese Silent Cinema era, The

Goddess was the debut feature for writer-director Wu Yonggang who started

his career as a set and costume designer with one of three major film

production companies in the 1920s, Dazhonghua Baihe, which later was co-opted

into Lianhua Film Company, the production house for The Goddess.

During his early years at Dazhonghua Baihe, Wu observed the increasing proliferation of prostitutes in the city (at the time, around 13% of the Shanghai’s women turned to prostitution as a means of making a living) and this experience left an indelible impression on the young man. From this latent image, the script and eventually, the film, The Goddess emerged. Wu took special care in recreating the world such a woman inhabited, from the symbolic and spartan set design, to the Deleuzian affection-image close-ups of the goddess. This film launched both Wu and its titular actress, the inimitable Ruan Lingyu, into renown and stardom respectively.

Born in 1907, Wu, a Shanghai native was considered to be one of the most prolific directors of the second generation (film directors). Wu had a strong leftist-leaning and was involved with the China Film Cultural Society, which in 1933 sought to convey Marxist ideals to the masses through films. The idea of using cinema as a means to convey social issues in order to stimulate the public conscience and debate was clearly present in The Goddess, as well as in Wu’s later films.

It is evident that The Goddess foregrounded Wu’s own ambivalent experience of Chinese modernity. Although his leftist credentials were an asset in the lead up to the Communist Revolution in 1949, his challenge of the Party’s restrictions on filmmakers in 1957 saw him banned from film making until 1962. Wu directed 24 films throughout his career. His last film, Night Rain at Bashan (1980), a meditation on the struggle of the Chinese people during the Gang of Four years, won Best Picture in the inaugural Golden Rooster Awards. The title took a line from a Tang Dynasty poem Written on a Rainy Night - A Letter to the North by Li Shangyin.

Wu died in 1980 at the age of 75.

During his early years at Dazhonghua Baihe, Wu observed the increasing proliferation of prostitutes in the city (at the time, around 13% of the Shanghai’s women turned to prostitution as a means of making a living) and this experience left an indelible impression on the young man. From this latent image, the script and eventually, the film, The Goddess emerged. Wu took special care in recreating the world such a woman inhabited, from the symbolic and spartan set design, to the Deleuzian affection-image close-ups of the goddess. This film launched both Wu and its titular actress, the inimitable Ruan Lingyu, into renown and stardom respectively.

Born in 1907, Wu, a Shanghai native was considered to be one of the most prolific directors of the second generation (film directors). Wu had a strong leftist-leaning and was involved with the China Film Cultural Society, which in 1933 sought to convey Marxist ideals to the masses through films. The idea of using cinema as a means to convey social issues in order to stimulate the public conscience and debate was clearly present in The Goddess, as well as in Wu’s later films.

It is evident that The Goddess foregrounded Wu’s own ambivalent experience of Chinese modernity. Although his leftist credentials were an asset in the lead up to the Communist Revolution in 1949, his challenge of the Party’s restrictions on filmmakers in 1957 saw him banned from film making until 1962. Wu directed 24 films throughout his career. His last film, Night Rain at Bashan (1980), a meditation on the struggle of the Chinese people during the Gang of Four years, won Best Picture in the inaugural Golden Rooster Awards. The title took a line from a Tang Dynasty poem Written on a Rainy Night - A Letter to the North by Li Shangyin.

Wu died in 1980 at the age of 75.

The Film:

The

Goddess’ allegorical take on a geopolitical Chinese

modernity is teased out in the film’s play on duality: a double life and a

double meaning; at once contradictory and ambivalent. The notion that things

are not what they seem, that meanings elude their confines. Wu’s elliptical

direction takes us into the invisible night of the flesh, and uncharted, these

actions are reborn again within the body of the mythical mother, and we see

both – her soul and its incarnation in earthly form.

In the opening title sequence of the film, a bas-relief sculpture depicting a mother, stripped bare with hands bound behind her back, is crouched over her naked infant; her body his shelter against the world. The title of the film The Goddess is projected onto this relief rendering this very earthly image into a seance with the divine. The faces on this relief were featureless, signifying the ubiquitous nature of the world we are about to enter, where the mother is unnamed, and her son, who is fatherless, cannot not bear a name in the societal terms. Together, they drift in a world where other characters were only known by their generic descriptives, of a class, or a type: ‘The Boss’, ‘The Principal’ – these roles epitomising either end of the social spectrum.

The film’s title: The Goddess, or simply Goddess(my preference) or Shennu in Pinyin (神女) signifies a duality. In Chinese the word ‘shennu’ describes a female divinity with supernatural powers often associated with the higher realms of spirituality. The word ‘shennu’ is also slang for a streetwalker.

The narrative follows the life of a young mother, the goddess, who raises her infant alone in the city, turning to streetwalking as her only means of survival. One night, having landed in a thug’s quarters whilst fleeing from the police, she becomes his possession. Despite her misfortunes, this loving mother finds a way to send her son to a prestigious school, in the believe that a good education would equip him with a better future. Her son thrives at school and all seems to be well until gossip about her surfaces. …

Whilst the story reads like a typical melodrama, Wu’s direction evoked a tonal splitting of the goddess as mother, streetwalker, and deity. There is little sensuality in Ruan’s goddess. In fact, the eye of the camera draws her space as that of domesticity, where the crib is placed in the centre of the room. We are introduced to this space through vignettes around the room, a dressing table full of powders and creams, a table with an assortment of tins and a doll; the camera then tilts up from the crib to her dress and continues to travel upwards to reveal a mother rocking her infant to sleep. As the young mother gets ready for her night of work, she was practical; her mannerisms of donning lipstick and fixing her hair were well rehearsed; it was only when she returns the next morning to sooth her crying child that we were treated with the first close-up of her. In this close-up, the goddess’ eyes were distant, but her face is as open as the night. Whilst her gaze eluded ours, as spectators, we were drawn to her as a ‘complex entity’, as a Deleuzian affect-image: in that each look is singular and resists being blended into the indifference of the world.

And yet, these same close-ups contributed to the commodification of Ruan. Her gaze beyond the frame projected us beyond the spatio-temporal confines of the film – imagined or hyper-extended by the audience. This close-up of Ruan is mesmerising because of our collective cinematic memory at work, recalling the glamour shots of Hollywood stars of the time, think Marlene Dietrich, Lilian Gish or Greta Garbo; the lighting, framing and angle, the slight tilt of the head, the finely-drawn eyebrows, all culminated in the objectification of her image – in a single close-up, a star was born.

But of course, the film is more than that. As a launch vehicle to stardom, it is a tragic one, for Ruan’s star status was short lived and ruinous. Instead, the repetition of close-ups throughout the film can be read in juxtaposition against that of the recurring shots of disembodied feet that walk across the frame, commensurate with the erasure of identity for the goddess herself. The first time we see her pick up a client, she deliberately looked down at her feet; and another time, Wu’s camera focused on two pairs of feet, first facing each other, and then walking off together. These shots articulate the pervasive anonymity of modern urban spaces, which are only synonymous with the transitory nature of the feet that walk through its landscape. These empty spaces cannot be defined by faces, especially not that of the close-up – which, especially for the goddess and Ruan, is the revelation of identity, individualism and dreams.

The finely modulated directorial style of Wu provides visual cues that signal a more complex layer of social critique at work. Take the first time the thug enters the goddess’ domestic space. He is caught as a reflection in her mirror. The second time, she saw his hat first before she sees him, indicating a symbolic order at work. In the opening sequence we see a lit window, where the frame of the window precurses the bars of the goddess’ jail cell. Vertical partitioning as metaphor for class divide: the large gates outside the school where she is often seen approaching, but never entering; or the top-down POV of her neighbour to the group of children below, intersected by three electrical wires, condemning the son as a ‘bastard’ and of the underclass. So too, the citizen-surveillance carried out by the goddess’ first neighbour (through a key-hole) and more overtly by her second neighbour, provides commentary on the ideological crack-down of the KMT government.

The famous shot of The Boss’ legs forming a dominating A-frame, between which the crouched figures of mother and son can be seen, is often interpreted as Wu making the viewer complicit to the male gaze. But does it? Unlike the trial scene where high-angle shots were used to show the three male judges pronouncing her sentence, in this frame, the goddess’ eyeline is upwards and out of frame. And we, as spectators find ourselves on the ground, on the same aspect level as she is. It would be fair to say that Wu, in fact, wanted his audience to empathise with the predicament of the goddess, rather than judge her. Where there was a social point to be made, Wu uses direct address, such as the goddess’ impassioned plea to the principal, made direct to camera, and later, as the film builds to its climax, the goddess’ incensed blow is one directed at her spectators. As the bottle shatters against the camera lens, the real erupts into our consciousness.

Wu’s camera and elliptical editing worked together to complicate the goddess’ private world and public life. From a scene of domesticity, we see in her two goddesses, the loving mother who cradles and rocks her infant to sleep is also a woman clad head to toe in a cheongsam; and the very act of buttoning up the high collar of her dress (which can be likened to a priest’s collar) further conceals her femininity – she becomes divine – she had donned her virtuous armour before heading into the night. The ‘night’ in question was also not the night locatable within the city streets of Shanghai, but was, in fact, the moral character of the city. Her nocturnal intrusions were framed by neon lights, gambling dens, fortune tellers. When finally we see her standing outside a pawn shop: the goddess’ commodification is complete – and a further doubling in the commercialisation of Ruan’s image. Her goddess, our inverse Madonna.

Ruan Lingyu

It is beyond a doubt that Ruan Lingyu’s performance in The Goddess propelled the success of this film and cemented its place in the filmic canon. Ruan was only twenty-four years old when she starred in the titular role, and with twenty-seven films already behind her. Most of her films, barring six, have all been lost.

Born Ruan Fenggen to a working-class family in 1910, she spent her early life navigating the tumultuous consequences of the 1911 Revolution led by Sun Yat-sen. After losing her father when she was six years old, her mother worked as a housekeeper for the wealthy Zhang family, whose fourth son, Zhang Damin, would later shape Ruan’s destiny.

At fifteen, Ruan replied to an ad at the Mingxing Film Company to become an actress. Within a year she landed a starring role in A Married Couple in Name Only (1927), and adopted Ruan Lingyu as her stage name; the director Bu Wancang paid special attention to the sense of maturity and elegance in her. Three years later, Ruan signed with the Lianhua Film Company (United Photoplay Service) and quickly made a name for herself, working with many of the best directors of the time, including Fei Mu, and Cai Chusheng.

Ruan’s versatility and range, particularly her ability to convey very finely nuanced emotions in close-ups gave her freedom to lose herself in the filmic art form within the silent cinema era. She was hailed as the Garbo of the Orient.

From very early on, Ruan was attracted to men who were ultimately too manipulative for her fragile heart. Her first love, Zhang Damin, was a gambler and the liar who eventually blackmailed her. Her love affair with Tang Jishan, a rich tea merchant was no better, he was a notorious womaniser. It was often observed that Ruan’s personal life imitated some of her more difficult on-screen roles.

On March 7th 1935, Ruan attended a banquet organised by Li Minwei (nicknamed the Father of Hong Kong Cinema) where she was seen to be in good spirits. But that night after a fierce argument with Tang, she asked her mother to make her some congee, which she consumed in the early hours of March 8th alongside the contents from two bottles of sleeping pills. She wrote two suicide notes before waking Tang. His hesitation in taking her to a well-equipped hospital ultimately caused her death. Ruan never regained consciousness and passed away that evening at 6:28pm.

Her two suicide notes were accusatory of the two men in her life and did not contain the much cited phrase “gossip is a fearful thing”. That note was in fact forged and circulated by Tang in an effort to save his own reputation.

It is not ironic that Ruan’s second last film was called New Women 新女性 (1935), an interrogation into the consequences of patriarchal system dressed up as a melodrama. The film was based upon the life of Ai Xia, the first Chinese actress to commit suicide in the same manner just a year prior to Ruan.

On March 14th, 300,000 people attended Ruan Lingyu's funeral procession that spanned over 3 miles (4.8 km). The New York times reported it as “the most spectacular funeral of the century”. What a pity they were paying tribute to her death.

Perhaps it is apt that we can now readily remember Ruan, her fragility and strength as well as her struggles, with anniversary of her death falling on International Woman’s Day (coined in the 70s) March 8th.

In the opening title sequence of the film, a bas-relief sculpture depicting a mother, stripped bare with hands bound behind her back, is crouched over her naked infant; her body his shelter against the world. The title of the film The Goddess is projected onto this relief rendering this very earthly image into a seance with the divine. The faces on this relief were featureless, signifying the ubiquitous nature of the world we are about to enter, where the mother is unnamed, and her son, who is fatherless, cannot not bear a name in the societal terms. Together, they drift in a world where other characters were only known by their generic descriptives, of a class, or a type: ‘The Boss’, ‘The Principal’ – these roles epitomising either end of the social spectrum.

The film’s title: The Goddess, or simply Goddess(my preference) or Shennu in Pinyin (神女) signifies a duality. In Chinese the word ‘shennu’ describes a female divinity with supernatural powers often associated with the higher realms of spirituality. The word ‘shennu’ is also slang for a streetwalker.

The narrative follows the life of a young mother, the goddess, who raises her infant alone in the city, turning to streetwalking as her only means of survival. One night, having landed in a thug’s quarters whilst fleeing from the police, she becomes his possession. Despite her misfortunes, this loving mother finds a way to send her son to a prestigious school, in the believe that a good education would equip him with a better future. Her son thrives at school and all seems to be well until gossip about her surfaces. …

Whilst the story reads like a typical melodrama, Wu’s direction evoked a tonal splitting of the goddess as mother, streetwalker, and deity. There is little sensuality in Ruan’s goddess. In fact, the eye of the camera draws her space as that of domesticity, where the crib is placed in the centre of the room. We are introduced to this space through vignettes around the room, a dressing table full of powders and creams, a table with an assortment of tins and a doll; the camera then tilts up from the crib to her dress and continues to travel upwards to reveal a mother rocking her infant to sleep. As the young mother gets ready for her night of work, she was practical; her mannerisms of donning lipstick and fixing her hair were well rehearsed; it was only when she returns the next morning to sooth her crying child that we were treated with the first close-up of her. In this close-up, the goddess’ eyes were distant, but her face is as open as the night. Whilst her gaze eluded ours, as spectators, we were drawn to her as a ‘complex entity’, as a Deleuzian affect-image: in that each look is singular and resists being blended into the indifference of the world.

And yet, these same close-ups contributed to the commodification of Ruan. Her gaze beyond the frame projected us beyond the spatio-temporal confines of the film – imagined or hyper-extended by the audience. This close-up of Ruan is mesmerising because of our collective cinematic memory at work, recalling the glamour shots of Hollywood stars of the time, think Marlene Dietrich, Lilian Gish or Greta Garbo; the lighting, framing and angle, the slight tilt of the head, the finely-drawn eyebrows, all culminated in the objectification of her image – in a single close-up, a star was born.

But of course, the film is more than that. As a launch vehicle to stardom, it is a tragic one, for Ruan’s star status was short lived and ruinous. Instead, the repetition of close-ups throughout the film can be read in juxtaposition against that of the recurring shots of disembodied feet that walk across the frame, commensurate with the erasure of identity for the goddess herself. The first time we see her pick up a client, she deliberately looked down at her feet; and another time, Wu’s camera focused on two pairs of feet, first facing each other, and then walking off together. These shots articulate the pervasive anonymity of modern urban spaces, which are only synonymous with the transitory nature of the feet that walk through its landscape. These empty spaces cannot be defined by faces, especially not that of the close-up – which, especially for the goddess and Ruan, is the revelation of identity, individualism and dreams.

The finely modulated directorial style of Wu provides visual cues that signal a more complex layer of social critique at work. Take the first time the thug enters the goddess’ domestic space. He is caught as a reflection in her mirror. The second time, she saw his hat first before she sees him, indicating a symbolic order at work. In the opening sequence we see a lit window, where the frame of the window precurses the bars of the goddess’ jail cell. Vertical partitioning as metaphor for class divide: the large gates outside the school where she is often seen approaching, but never entering; or the top-down POV of her neighbour to the group of children below, intersected by three electrical wires, condemning the son as a ‘bastard’ and of the underclass. So too, the citizen-surveillance carried out by the goddess’ first neighbour (through a key-hole) and more overtly by her second neighbour, provides commentary on the ideological crack-down of the KMT government.

The famous shot of The Boss’ legs forming a dominating A-frame, between which the crouched figures of mother and son can be seen, is often interpreted as Wu making the viewer complicit to the male gaze. But does it? Unlike the trial scene where high-angle shots were used to show the three male judges pronouncing her sentence, in this frame, the goddess’ eyeline is upwards and out of frame. And we, as spectators find ourselves on the ground, on the same aspect level as she is. It would be fair to say that Wu, in fact, wanted his audience to empathise with the predicament of the goddess, rather than judge her. Where there was a social point to be made, Wu uses direct address, such as the goddess’ impassioned plea to the principal, made direct to camera, and later, as the film builds to its climax, the goddess’ incensed blow is one directed at her spectators. As the bottle shatters against the camera lens, the real erupts into our consciousness.

Wu’s camera and elliptical editing worked together to complicate the goddess’ private world and public life. From a scene of domesticity, we see in her two goddesses, the loving mother who cradles and rocks her infant to sleep is also a woman clad head to toe in a cheongsam; and the very act of buttoning up the high collar of her dress (which can be likened to a priest’s collar) further conceals her femininity – she becomes divine – she had donned her virtuous armour before heading into the night. The ‘night’ in question was also not the night locatable within the city streets of Shanghai, but was, in fact, the moral character of the city. Her nocturnal intrusions were framed by neon lights, gambling dens, fortune tellers. When finally we see her standing outside a pawn shop: the goddess’ commodification is complete – and a further doubling in the commercialisation of Ruan’s image. Her goddess, our inverse Madonna.

Ruan Lingyu

It is beyond a doubt that Ruan Lingyu’s performance in The Goddess propelled the success of this film and cemented its place in the filmic canon. Ruan was only twenty-four years old when she starred in the titular role, and with twenty-seven films already behind her. Most of her films, barring six, have all been lost.

Born Ruan Fenggen to a working-class family in 1910, she spent her early life navigating the tumultuous consequences of the 1911 Revolution led by Sun Yat-sen. After losing her father when she was six years old, her mother worked as a housekeeper for the wealthy Zhang family, whose fourth son, Zhang Damin, would later shape Ruan’s destiny.

At fifteen, Ruan replied to an ad at the Mingxing Film Company to become an actress. Within a year she landed a starring role in A Married Couple in Name Only (1927), and adopted Ruan Lingyu as her stage name; the director Bu Wancang paid special attention to the sense of maturity and elegance in her. Three years later, Ruan signed with the Lianhua Film Company (United Photoplay Service) and quickly made a name for herself, working with many of the best directors of the time, including Fei Mu, and Cai Chusheng.

Ruan’s versatility and range, particularly her ability to convey very finely nuanced emotions in close-ups gave her freedom to lose herself in the filmic art form within the silent cinema era. She was hailed as the Garbo of the Orient.

From very early on, Ruan was attracted to men who were ultimately too manipulative for her fragile heart. Her first love, Zhang Damin, was a gambler and the liar who eventually blackmailed her. Her love affair with Tang Jishan, a rich tea merchant was no better, he was a notorious womaniser. It was often observed that Ruan’s personal life imitated some of her more difficult on-screen roles.

On March 7th 1935, Ruan attended a banquet organised by Li Minwei (nicknamed the Father of Hong Kong Cinema) where she was seen to be in good spirits. But that night after a fierce argument with Tang, she asked her mother to make her some congee, which she consumed in the early hours of March 8th alongside the contents from two bottles of sleeping pills. She wrote two suicide notes before waking Tang. His hesitation in taking her to a well-equipped hospital ultimately caused her death. Ruan never regained consciousness and passed away that evening at 6:28pm.

Her two suicide notes were accusatory of the two men in her life and did not contain the much cited phrase “gossip is a fearful thing”. That note was in fact forged and circulated by Tang in an effort to save his own reputation.

It is not ironic that Ruan’s second last film was called New Women 新女性 (1935), an interrogation into the consequences of patriarchal system dressed up as a melodrama. The film was based upon the life of Ai Xia, the first Chinese actress to commit suicide in the same manner just a year prior to Ruan.

On March 14th, 300,000 people attended Ruan Lingyu's funeral procession that spanned over 3 miles (4.8 km). The New York times reported it as “the most spectacular funeral of the century”. What a pity they were paying tribute to her death.

Perhaps it is apt that we can now readily remember Ruan, her fragility and strength as well as her struggles, with anniversary of her death falling on International Woman’s Day (coined in the 70s) March 8th.

The Restoration:

The digital restoration of The Goddess was made possible courtesy

of the China Film Archive in 2014 and funded by SAPPRFT, in association with

the K T Wong Foundation and the BFI. The premiere screening showcased a new

score by Zou Ye, commissioned by the K T Wong Foundation. It drew on aesthetical

elements from both Eastern and Western culture – a reimagining of the ambience

of a Shanghai/Paris of the 1930s. It was performed live by the English Chamber

Orchestra, conducted by Nicholas Chalme for the London Film Festival, 14

October 2014 at Queen Elizabeth Hall.

Credits:

Shénnǚ, 神女 | Dir: WÚ Yǒnggāng | China | 1934 | 85 mins | 2K DCP (orig. 35mm) | B&W | 1.33:1 | Silent, with pre-recorded musical accompaniment | Traditional Chinese intertitles, with Eng. subtitles | U/C15+.

Production Company: Lianhua Film Company | Producer: LUÓ Míngyòu | Script: WÚ | Photography: HÓNG Wěiliè | Art Dir: WÚ | Music (new score for 2014 restoration): ZŌU Yě.

Cast: RUǍN Língyù (‘The Goddess’), ZHING Zhizhí (‘Boss Zhang’), ‘Henry Lai’ Lí kēng (‘Her Son’), LǏ Jūnpán (‘The Principal’).

Source: China Film Archive.

Credits:

Shénnǚ, 神女 | Dir: WÚ Yǒnggāng | China | 1934 | 85 mins | 2K DCP (orig. 35mm) | B&W | 1.33:1 | Silent, with pre-recorded musical accompaniment | Traditional Chinese intertitles, with Eng. subtitles | U/C15+.

Production Company: Lianhua Film Company | Producer: LUÓ Míngyòu | Script: WÚ | Photography: HÓNG Wěiliè | Art Dir: WÚ | Music (new score for 2014 restoration): ZŌU Yě.

Cast: RUǍN Língyù (‘The Goddess’), ZHING Zhizhí (‘Boss Zhang’), ‘Henry Lai’ Lí kēng (‘Her Son’), LǏ Jūnpán (‘The Principal’).

Source: China Film Archive.