TEN YEARS AFTER...TEN YEARS OLDER (1986)

+ THE BUTLER (1997)

![]()

Randwick Ritz, Sydney:

4:15 PM

Saturday 03 May

Lido Cinemas, Melbourne:

2:25 PM

Saturday 10 May

Rating: M

Duration: 35 minutes + 58 minutes

Country: Australia

Language: English

Cast: Anna Kannava, Nino Kannava

Director: Anna Kannava

SYDNEY TICKETS ⟶

MELBOURNE TICKETS ⟶

4:15 PM

Saturday 03 May

Lido Cinemas, Melbourne:

2:25 PM

Saturday 10 May

Rating: M

Duration: 35 minutes + 58 minutes

Country: Australia

Language: English

Cast: Anna Kannava, Nino Kannava

Director: Anna Kannava

SYDNEY TICKETS ⟶

MELBOURNE TICKETS ⟶

4K RESTORATION - WORLD PREMIERE

‘I was very moved by The Butler, a portrait of Anna's brother, Nino. This film has one of those unexpected moments of grace that totally won me over – it brought tears to my eyes (not of sadness, but of happiness and liberation).’– Cristina Álvarez López

‘I was struck by the absolute coherence of her relatively small but impressive and enduring output.’ – Adrian Martin

Celebrating the filmmaking of Anna Kannava (1959-2011) with two remarkable autobiographical documentaries, recently restored in 4K.

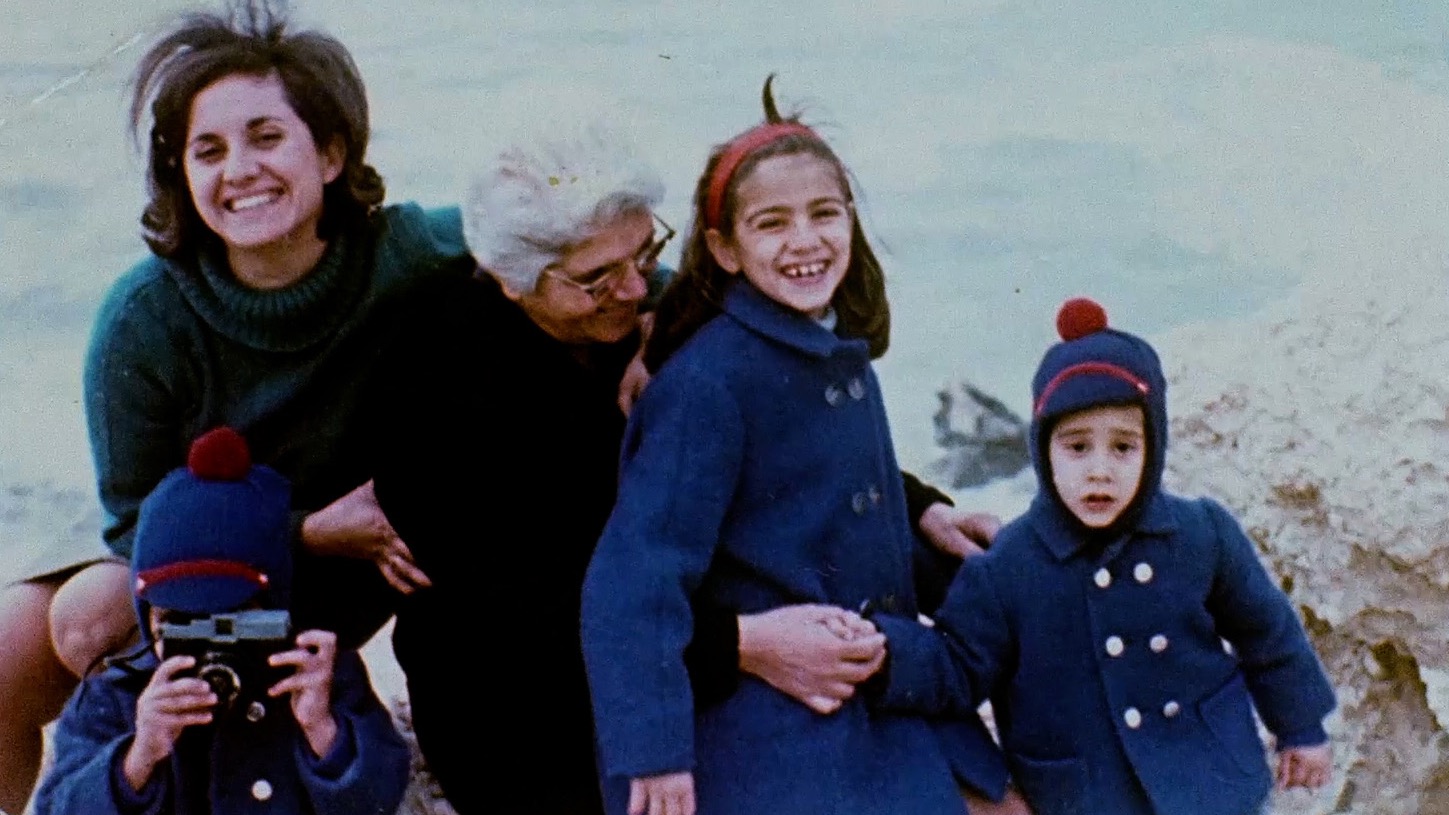

Born in Cyprus, Kannava migrated to Melbourne with her family in 1974. In the meditative Ten Years After…Ten Years Older, the director tenderly reflects on returning to her homeland after a decade away. In the deftly comedic and deeply affecting The Butler, Kannava impressionistically portrays the life she shared with her devoted younger brother Nino. These two key works reveal a gifted filmmaker deserving of widespread recognition.

Introduced by John Cruthers at Ritz Cinemas and by Simon Wilmot at Lido Cinemas

‘I was very moved by The Butler, a portrait of Anna's brother, Nino. This film has one of those unexpected moments of grace that totally won me over – it brought tears to my eyes (not of sadness, but of happiness and liberation).’– Cristina Álvarez López

‘I was struck by the absolute coherence of her relatively small but impressive and enduring output.’ – Adrian Martin

Celebrating the filmmaking of Anna Kannava (1959-2011) with two remarkable autobiographical documentaries, recently restored in 4K.

Born in Cyprus, Kannava migrated to Melbourne with her family in 1974. In the meditative Ten Years After…Ten Years Older, the director tenderly reflects on returning to her homeland after a decade away. In the deftly comedic and deeply affecting The Butler, Kannava impressionistically portrays the life she shared with her devoted younger brother Nino. These two key works reveal a gifted filmmaker deserving of widespread recognition.

Introduced by John Cruthers at Ritz Cinemas and by Simon Wilmot at Lido Cinemas

FILM NOTES

By Bill Mousoulis and Frankie Kanatas

Bill Mousoulis is an independent filmmaker and founder of Senses of Cinema.

Frankie Kanatas is a Greek-Australian writer and film critic.

ANNA KANNAVA

Anna Kannava

(1959-2011) was a distinctive figure in the Australian film landscape in her

all-too-brief career and life. Born in Cyprus in 1959, she migrated to

Australia in 1974 with her mother and brothers. She quickly learnt English at

high school in Melbourne and then studied drama, film, screenwriting,

photography and fine art at Deakin University (Rusden College), where she

graduated in 1982 with a Bachelor of Education in Drama and Media. In those

university years, she made several experimental and feminist films, a couple of

them co-directed with Annie Duncan.

After this initial burst of study and self-discovery however, her thoughts turned to her roots in Cyprus, especially to her grandmother who chose to remain in her traditional house in Limassol in Cyprus rather than also migrate to Australia. Kannava equipped herself with a cheap 16mm Bolex camera and travelled to Limassol to re-unite with her grandmother and film the reflective and observational documentary, Ten Years After ... Ten Years Older (1986). This was followed by a quirky silent comedy, Vanilla Essence (1989), in which Kannava’s thoughts turned back to fiction and strong female characters.

In 1990 however, when she was 30 years old, Kannava was unexpectedly diagnosed with scleroderma (a hardening and tightening of the skin, as well as the lungs and organs). This limited her capabilities, but she continued working and she made another personal documentary, this one on her entire family and also her health condition: The Butler (1997), which is her masterpiece.

The two personal documentaries that Kannava made were a catharsis for her, as she then went on to make more traditional (but still distinctive) narrative feature films: Dreams for Life (2004) and Kissing Paris (2008). She also wrote novels during this time: Stefanos of Limassol (published by Ilura Press in 2012) and So Much Joy – Lisboa! (unpublished).

Kannava’s life was tragically cut short at the age of 51 in 2011, her scleroderma combining with cancer to take her life. She will be remembered as an individual with great spirit and passion, with a matching generous personality.

After this initial burst of study and self-discovery however, her thoughts turned to her roots in Cyprus, especially to her grandmother who chose to remain in her traditional house in Limassol in Cyprus rather than also migrate to Australia. Kannava equipped herself with a cheap 16mm Bolex camera and travelled to Limassol to re-unite with her grandmother and film the reflective and observational documentary, Ten Years After ... Ten Years Older (1986). This was followed by a quirky silent comedy, Vanilla Essence (1989), in which Kannava’s thoughts turned back to fiction and strong female characters.

In 1990 however, when she was 30 years old, Kannava was unexpectedly diagnosed with scleroderma (a hardening and tightening of the skin, as well as the lungs and organs). This limited her capabilities, but she continued working and she made another personal documentary, this one on her entire family and also her health condition: The Butler (1997), which is her masterpiece.

The two personal documentaries that Kannava made were a catharsis for her, as she then went on to make more traditional (but still distinctive) narrative feature films: Dreams for Life (2004) and Kissing Paris (2008). She also wrote novels during this time: Stefanos of Limassol (published by Ilura Press in 2012) and So Much Joy – Lisboa! (unpublished).

Kannava’s life was tragically cut short at the age of 51 in 2011, her scleroderma combining with cancer to take her life. She will be remembered as an individual with great spirit and passion, with a matching generous personality.

THE FILM

Ten Years After ... Ten Years Older

Director Anna Kannava’s family history had many layers. Her grandmother Anna Apokidou, in Cyprus, was childless, but she and her husband decided to adopt an 8-year old niece of theirs, Frederika. Anna elder loved Frederika dearly, but her husband died three years later, rendering her a single mother. This created a resolve within Anna to love Frederika even more. Frederika grew up and got married at 19, but she and her husband eventually split up, and then Turkey invaded Cyprus in 1974, so Frederika made the decision to migrate to Australia with her three children (Anna, George and Ninos).

The 15-year-old Anna Kannava felt displaced, as she left her friends and life behind, but she was also excited by the possibilities of a new life in Australia.

After experiencing the typical student life in her early 20s, however, including living in a bohemian share-household and making experimental/feminist short films (together with fellow student Annie Duncan), Kannava became reflective and wondered about her previous life. She decided, at the age of 25, to return to Cyprus, in particular her home-city of Limassol, to re-unite with her grandmother and to make a documentary about this. And so, the film Ten Years After … Ten Years Older (1986) was made, a beautiful time-capsule film, capturing not only the sights and sounds of the traditional but lively city of Limassol in the mid-1980s, but also Kannava’s existential soul at this delicately liminal moment between the past and the future.

Ever the intrepid DIY independent filmmaker (though she would eventually be funded and work with big crews on some of her projects), Kannava had bought herself a portable Bolex 16mm camera and also had assistance from her boyfriend Leigh Sloggett, who accompanied her to Cyprus. They filmed the images and recorded the sounds separately (their equipment was limited: the Bolex could not synchronise with their sound recorder), and the film was picture and sound edited back in Australia (with help from fellow ex-student Simon Wilmot and a grant from the Australian Film Commission).

Ten Years After … Ten Years Older has a surety of hand that is quite remarkable for a 25-year-old filmmaker. The film is a layered blend of elements: documentary footage, acted reconstructions, voice-over narration, collage editing, and music. It reminds one of the highly individuated personal voice-over documentaries of figures such as Agnès Varda or Chantal Akerman, strong psychological works about identity and family connections without being overtly feminist films. Kannava had good grounding: a love of the arts when she was a child, which developed into a love of European art cinema when she was in Melbourne, and then an inspirational main lecturer at Rusden College (now Deakin University), Graeme Cutts, (and other tutors there such as Brian McKenzie and Ray Argall also gave her great impetus). (1)

The formal element of the first-person voice-over that anchors Ten Years After … Ten Years Older was seemingly a natural and intuitive choice for Kannava. She said that ‘The voice-over just comes to me; I have no control over it.’ (2) Distinctively delivered in Kannava’s Cypriot accent, it allows space for the images to exist in their own right, in a way alternating with them through the course of the film. The images are simultaneously quotidian and charged (with memory, longing and awe): the stoic and haunted but also wise and loving grandmother; cafes and bakeries and farms and weddings with their traditional rituals; streets teeming with markets and handsome young men; and, acutely, the old stone house the grandmother lives in. The voice-over has a poetic lyricism to it that is descriptive but also heart-rending: ‘I feel I have been cheated of so many more memories’, ‘Time didn’t wait for me’, ‘The only time machine there was, was my memory’, ‘I have two countries, both very beautiful in their own ways.’

In the film, Kannava’s grandmother expresses her desire to see the young Anna married, to make the wedding gown for her. Sadly, Anna Kannava’s life had more twists and turns ahead for her: her health would hamper her and she would never marry or have children of her own, and she even died before her grandmother did (Anna died at 51 in 2011 and her grandmother died on the cusp of 100 a couple of years later). These historical layers that we ourselves know now lend Ten Years After … Ten Years Older an even greater poignancy and power.

Notes

1. See a detailed description Kannava offered to the web-based database, Melbourne Independent Filmmakers, in 2004: http://innersense.com.au/mif/kannava.html

2. Kannava, as above.

Film notes by Bill Mousoulis

Director Anna Kannava’s family history had many layers. Her grandmother Anna Apokidou, in Cyprus, was childless, but she and her husband decided to adopt an 8-year old niece of theirs, Frederika. Anna elder loved Frederika dearly, but her husband died three years later, rendering her a single mother. This created a resolve within Anna to love Frederika even more. Frederika grew up and got married at 19, but she and her husband eventually split up, and then Turkey invaded Cyprus in 1974, so Frederika made the decision to migrate to Australia with her three children (Anna, George and Ninos).

The 15-year-old Anna Kannava felt displaced, as she left her friends and life behind, but she was also excited by the possibilities of a new life in Australia.

After experiencing the typical student life in her early 20s, however, including living in a bohemian share-household and making experimental/feminist short films (together with fellow student Annie Duncan), Kannava became reflective and wondered about her previous life. She decided, at the age of 25, to return to Cyprus, in particular her home-city of Limassol, to re-unite with her grandmother and to make a documentary about this. And so, the film Ten Years After … Ten Years Older (1986) was made, a beautiful time-capsule film, capturing not only the sights and sounds of the traditional but lively city of Limassol in the mid-1980s, but also Kannava’s existential soul at this delicately liminal moment between the past and the future.

Ever the intrepid DIY independent filmmaker (though she would eventually be funded and work with big crews on some of her projects), Kannava had bought herself a portable Bolex 16mm camera and also had assistance from her boyfriend Leigh Sloggett, who accompanied her to Cyprus. They filmed the images and recorded the sounds separately (their equipment was limited: the Bolex could not synchronise with their sound recorder), and the film was picture and sound edited back in Australia (with help from fellow ex-student Simon Wilmot and a grant from the Australian Film Commission).

Ten Years After … Ten Years Older has a surety of hand that is quite remarkable for a 25-year-old filmmaker. The film is a layered blend of elements: documentary footage, acted reconstructions, voice-over narration, collage editing, and music. It reminds one of the highly individuated personal voice-over documentaries of figures such as Agnès Varda or Chantal Akerman, strong psychological works about identity and family connections without being overtly feminist films. Kannava had good grounding: a love of the arts when she was a child, which developed into a love of European art cinema when she was in Melbourne, and then an inspirational main lecturer at Rusden College (now Deakin University), Graeme Cutts, (and other tutors there such as Brian McKenzie and Ray Argall also gave her great impetus). (1)

The formal element of the first-person voice-over that anchors Ten Years After … Ten Years Older was seemingly a natural and intuitive choice for Kannava. She said that ‘The voice-over just comes to me; I have no control over it.’ (2) Distinctively delivered in Kannava’s Cypriot accent, it allows space for the images to exist in their own right, in a way alternating with them through the course of the film. The images are simultaneously quotidian and charged (with memory, longing and awe): the stoic and haunted but also wise and loving grandmother; cafes and bakeries and farms and weddings with their traditional rituals; streets teeming with markets and handsome young men; and, acutely, the old stone house the grandmother lives in. The voice-over has a poetic lyricism to it that is descriptive but also heart-rending: ‘I feel I have been cheated of so many more memories’, ‘Time didn’t wait for me’, ‘The only time machine there was, was my memory’, ‘I have two countries, both very beautiful in their own ways.’

In the film, Kannava’s grandmother expresses her desire to see the young Anna married, to make the wedding gown for her. Sadly, Anna Kannava’s life had more twists and turns ahead for her: her health would hamper her and she would never marry or have children of her own, and she even died before her grandmother did (Anna died at 51 in 2011 and her grandmother died on the cusp of 100 a couple of years later). These historical layers that we ourselves know now lend Ten Years After … Ten Years Older an even greater poignancy and power.

Notes

1. See a detailed description Kannava offered to the web-based database, Melbourne Independent Filmmakers, in 2004: http://innersense.com.au/mif/kannava.html

2. Kannava, as above.

Film notes by Bill Mousoulis

THE FILM

The

Butler

Over the end credits of The Butler (1997), folk musician Dionysis Savvopoulos sings, ‘The thing that eats me, the thing that saves me, is that I can dream like a Karagiozi’, likening himself to the shadow puppet from Greek folklore. Savvopoulos’ music was likely a formative influence on director Anna Kannava; three of his songs feature on this film's soundtrack, and his record, I Perivoli Tou Trellou (The Madman’s Garden), appears in the background of a scene where Kannava and her brothers pool coins together for treats. Savvopoulos’ lyrics, weaving themes of dreaming, recovery and homecoming, get to the very heart of the film.

Kannava’s documentary filmmaking journey began a decade earlier with Ten Years After… Ten Years Older (1986), and continues in The Butler, where she now broadens her scope beyond her birthplace and grandmother. This film begins as a portrait of her younger brother Nino, the eponymous butler whom Kannava once likened to a real-life amalgamation of Mr. Bean, Peter Sellers in The Pink Panther and Jerry Lewis before gradually transforming into a portrait of her entire family. (1)

Her approach to telling their story is distinct. She eschews the obvious political angles that tend to dominate migration narratives and instead depicts her family as existing in a world that transcends national Greek-Cypriot or Australian identities. Kannava employs various techniques to situate the audience into her family’s shared mental landscape, including dramatised representations of the past, essay-like collages of photos and the use of past films.

Kannava’s ingenuity shines in these dramatic representations of the past. In one particularly moving sequence, she juxtaposes scenes from a Greek melodrama, Orfani Se Xena Heria (Orphan In Foreign Hands, Errikos Thalassinos, 1962), that she watched at Melbourne’s Astor Cinema, with a performance by her siblings and herself singing a song from the film at home. The song ‘Sinnefiasmeni Kiriaki’ (‘Cloudy Sunday’), by Vasilis Tsitsanis, written during the German-Italian Occupation of Greece during World War II, has become a Greek national anthem of sorts – a cry of pain, resignation, hope and resilience.

It is in the above sequence that Kannava demonstrates that specificity can be a gateway to universality, as, anecdotally, many children of Greek-Cypriot migrants recall going to the Astor to watch Greek films and know this particular song. Despite its universal nature, however, the sequence remains searingly personal, ending with the admission that, had it not been for these games, she’s not sure she and her brothers would have survived their transition into this new world.

Dreaming forms the essence of the Kannava family’s mental landscape, enabling them to express their aspirations while remaining mindful of their abilities. Nino's role-playing as Anna’s therapist and a pilot particularly resonates, as these scenes showcase the power of imaginative play to connect us to our deepest desires. There is, however, a crucial distinction between pretend play in adulthood and childhood – the stinging realisation that some dreams are destined to remain unfulfilled. In this scene, Savvopoulos’ song, ‘To Perivoli’ (The Garden) sums up the story of Kannava and her family: ‘Alone for so many years I was struggling blindly, and travelled and I got sick and I've gone through many ordeals, But the time has come for me to walk again beside you, into the colours of your garden by the seashore.’ As Savvopoulos’ lyrics press home, dreams are double-edged swords, offering both inspiration and agony to those who hold them.

In the film’s penultimate scene, Kannava reveals personal details, sharing her experience with scleroderma, an autoimmune disease that causes the skin to grow hard and tight around the body. She addresses her chronic illness and alienation through narration, gazing into the mirror, highlighting the disconnect between her former self and the stranger she now sees staring back at her. While the entire film, and this scene in particular, likely served as a personal catharsis, Kannava chooses to end on a universally uplifting note, featuring a coastal walk and a Greek dance, where she passes the familial torch to her niece and nephew, the next generation of Kannavas. At the same time, she gently invites the audience to embrace life’s simple pleasures and reflect on their histories, perhaps finding something extraordinary within the ordinary, as she did. I promise Anna, I will.

Notes

(1) Lisa French (ed.), Womenvision: Women and the Moving Image in Australia. Damned Publishing Melbourne, 2003, p. 162).

Film note by Frankie Kanatas

Over the end credits of The Butler (1997), folk musician Dionysis Savvopoulos sings, ‘The thing that eats me, the thing that saves me, is that I can dream like a Karagiozi’, likening himself to the shadow puppet from Greek folklore. Savvopoulos’ music was likely a formative influence on director Anna Kannava; three of his songs feature on this film's soundtrack, and his record, I Perivoli Tou Trellou (The Madman’s Garden), appears in the background of a scene where Kannava and her brothers pool coins together for treats. Savvopoulos’ lyrics, weaving themes of dreaming, recovery and homecoming, get to the very heart of the film.

Kannava’s documentary filmmaking journey began a decade earlier with Ten Years After… Ten Years Older (1986), and continues in The Butler, where she now broadens her scope beyond her birthplace and grandmother. This film begins as a portrait of her younger brother Nino, the eponymous butler whom Kannava once likened to a real-life amalgamation of Mr. Bean, Peter Sellers in The Pink Panther and Jerry Lewis before gradually transforming into a portrait of her entire family. (1)

Her approach to telling their story is distinct. She eschews the obvious political angles that tend to dominate migration narratives and instead depicts her family as existing in a world that transcends national Greek-Cypriot or Australian identities. Kannava employs various techniques to situate the audience into her family’s shared mental landscape, including dramatised representations of the past, essay-like collages of photos and the use of past films.

Kannava’s ingenuity shines in these dramatic representations of the past. In one particularly moving sequence, she juxtaposes scenes from a Greek melodrama, Orfani Se Xena Heria (Orphan In Foreign Hands, Errikos Thalassinos, 1962), that she watched at Melbourne’s Astor Cinema, with a performance by her siblings and herself singing a song from the film at home. The song ‘Sinnefiasmeni Kiriaki’ (‘Cloudy Sunday’), by Vasilis Tsitsanis, written during the German-Italian Occupation of Greece during World War II, has become a Greek national anthem of sorts – a cry of pain, resignation, hope and resilience.

It is in the above sequence that Kannava demonstrates that specificity can be a gateway to universality, as, anecdotally, many children of Greek-Cypriot migrants recall going to the Astor to watch Greek films and know this particular song. Despite its universal nature, however, the sequence remains searingly personal, ending with the admission that, had it not been for these games, she’s not sure she and her brothers would have survived their transition into this new world.

Dreaming forms the essence of the Kannava family’s mental landscape, enabling them to express their aspirations while remaining mindful of their abilities. Nino's role-playing as Anna’s therapist and a pilot particularly resonates, as these scenes showcase the power of imaginative play to connect us to our deepest desires. There is, however, a crucial distinction between pretend play in adulthood and childhood – the stinging realisation that some dreams are destined to remain unfulfilled. In this scene, Savvopoulos’ song, ‘To Perivoli’ (The Garden) sums up the story of Kannava and her family: ‘Alone for so many years I was struggling blindly, and travelled and I got sick and I've gone through many ordeals, But the time has come for me to walk again beside you, into the colours of your garden by the seashore.’ As Savvopoulos’ lyrics press home, dreams are double-edged swords, offering both inspiration and agony to those who hold them.

In the film’s penultimate scene, Kannava reveals personal details, sharing her experience with scleroderma, an autoimmune disease that causes the skin to grow hard and tight around the body. She addresses her chronic illness and alienation through narration, gazing into the mirror, highlighting the disconnect between her former self and the stranger she now sees staring back at her. While the entire film, and this scene in particular, likely served as a personal catharsis, Kannava chooses to end on a universally uplifting note, featuring a coastal walk and a Greek dance, where she passes the familial torch to her niece and nephew, the next generation of Kannavas. At the same time, she gently invites the audience to embrace life’s simple pleasures and reflect on their histories, perhaps finding something extraordinary within the ordinary, as she did. I promise Anna, I will.

Notes

(1) Lisa French (ed.), Womenvision: Women and the Moving Image in Australia. Damned Publishing Melbourne, 2003, p. 162).

Film note by Frankie Kanatas

THE RESTORATION

Ten Years After ... Ten Years Older

Source: DCP John Cruthers

Restored in 2K from the original A&B roll 16mm negative. Scanned and graded by Grayton Hevern at Complete Post. Audio digitised from the 16mm magnetic master by Simon Wilmot at Deakin University. Further grade and restoration work by Bill Mousoulis and Ray Argall. Final mastering and DCP by Piccolo Films.

Director/Writer/Producer/Camera: Anna Kannava; Produced with the assistance of the Australian Film Commission; Assistance on Location/Assistant Director: Leigh Sloggett; Advisors: Brian McKenzie, John Cruthers; Sound Editor: Simon Wilmot; Animation: Lisa Parrish

Featuring: Anna Apokidou and Anna Kannava as themselves

Elena Kannava (Young Anna)

Australia | 1986 | 35 Mins | 4k DCP | Colour | English | PG

The Butler

Source: DCP John Cruthers

Restored from 16mm A&B roll negative and digital components of archival materials supplied by Producer John Cruthers, Bill Mousoulis and Kannava’s estate. Digital audio mono supplied by NFSA. A version was made with Greek subtitles, for the family and festival audience(s) in Cyprus. Restoration work was financed by the film producer, John Cruthers, and Anna Kannava’s mother Frederika Apokidou, with assistance from Piccolo Films and Bill Mousoulis. Greek Subtitles translated by Frederika Apokidou. Digital restoration by Piccolo Films in 2022.

Director/Writer: Anna Kannava; Production Company: Huzzah Productions, Developed with the assistance of the Australian Film Commission, Produced with the assistance of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and Film Victoria; Producer: John Cruthers; Script Editor: Brian McKenzie; Photography: Firouz Malekzadeh, Brian McKenzie; Editor: James Manche; Sound Editor: Livia Ruzic

Cast: Chrystal Hili (Young Anna), Salvatore Latona (Young Ninos), James Biviano (Young George), Members of the Kannava family as themselves.

Australia | 1997 | 58 Mins | 4K DCP | Colour | English | PG

Source: DCP John Cruthers

Restored in 2K from the original A&B roll 16mm negative. Scanned and graded by Grayton Hevern at Complete Post. Audio digitised from the 16mm magnetic master by Simon Wilmot at Deakin University. Further grade and restoration work by Bill Mousoulis and Ray Argall. Final mastering and DCP by Piccolo Films.

Director/Writer/Producer/Camera: Anna Kannava; Produced with the assistance of the Australian Film Commission; Assistance on Location/Assistant Director: Leigh Sloggett; Advisors: Brian McKenzie, John Cruthers; Sound Editor: Simon Wilmot; Animation: Lisa Parrish

Featuring: Anna Apokidou and Anna Kannava as themselves

Elena Kannava (Young Anna)

Australia | 1986 | 35 Mins | 4k DCP | Colour | English | PG

The Butler

Source: DCP John Cruthers

Restored from 16mm A&B roll negative and digital components of archival materials supplied by Producer John Cruthers, Bill Mousoulis and Kannava’s estate. Digital audio mono supplied by NFSA. A version was made with Greek subtitles, for the family and festival audience(s) in Cyprus. Restoration work was financed by the film producer, John Cruthers, and Anna Kannava’s mother Frederika Apokidou, with assistance from Piccolo Films and Bill Mousoulis. Greek Subtitles translated by Frederika Apokidou. Digital restoration by Piccolo Films in 2022.

Director/Writer: Anna Kannava; Production Company: Huzzah Productions, Developed with the assistance of the Australian Film Commission, Produced with the assistance of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and Film Victoria; Producer: John Cruthers; Script Editor: Brian McKenzie; Photography: Firouz Malekzadeh, Brian McKenzie; Editor: James Manche; Sound Editor: Livia Ruzic

Cast: Chrystal Hili (Young Anna), Salvatore Latona (Young Ninos), James Biviano (Young George), Members of the Kannava family as themselves.

Australia | 1997 | 58 Mins | 4K DCP | Colour | English | PG