STELLA DALLAS (1925)

![]()

Randwick Ritz, Sydney:

10:00 AM

Sunday May 04

Lido Cinemas, Melbourne:

10:30 AM

Sunday May 11

Rating: PG

Duration: 110 minutes

Country: USA

Language: English. Silent with recorded score

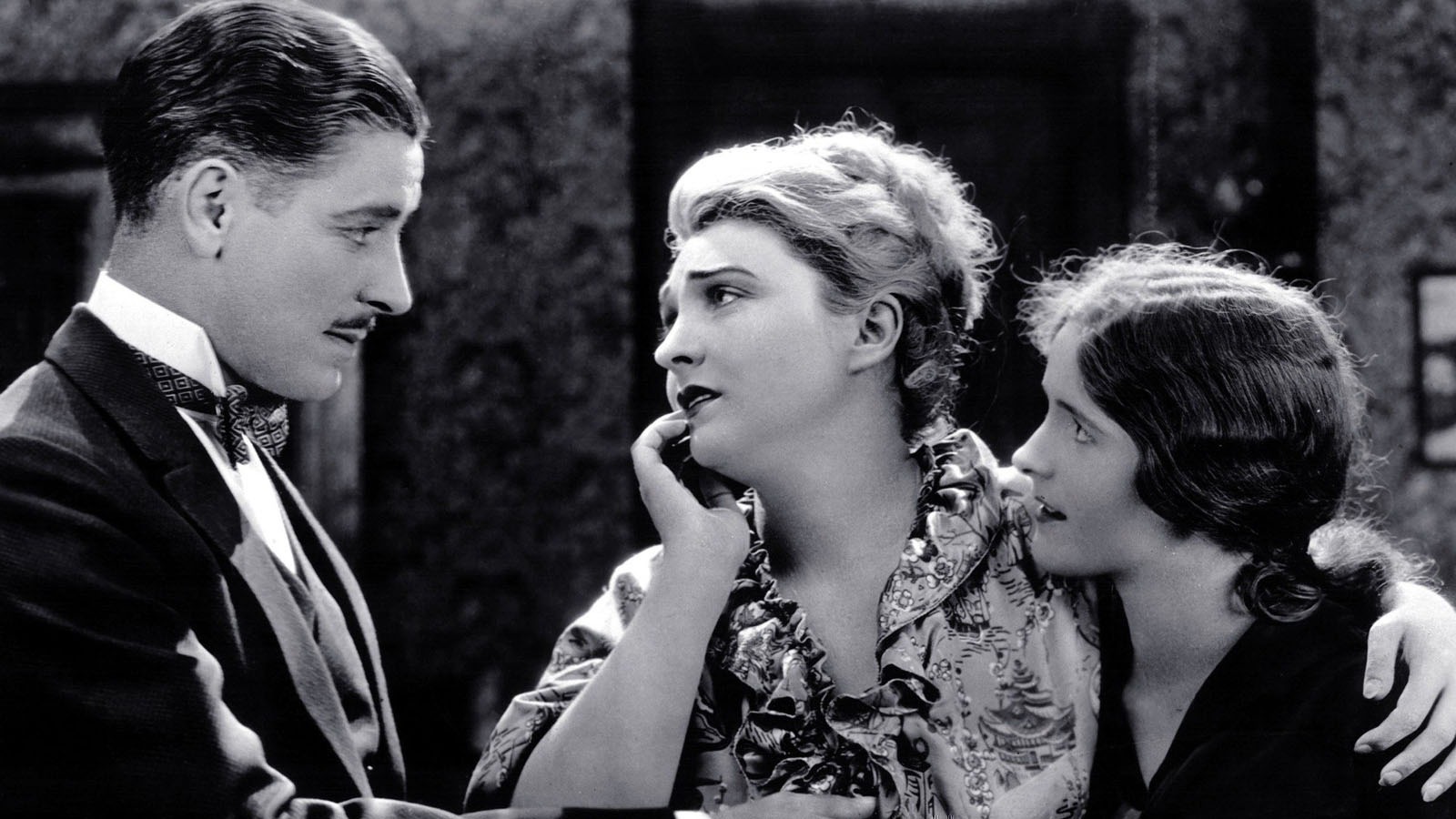

Cast: Ronald Colman, Belle Bennett, Lois Moran

Director: Henry King

SYDNEY TICKETS ⟶

MELBOURNE TICKETS ⟶

10:00 AM

Sunday May 04

Lido Cinemas, Melbourne:

10:30 AM

Sunday May 11

Rating: PG

Duration: 110 minutes

Country: USA

Language: English. Silent with recorded score

Cast: Ronald Colman, Belle Bennett, Lois Moran

Director: Henry King

SYDNEY TICKETS ⟶

MELBOURNE TICKETS ⟶

4K RESTORATION – AUSTRALIAN PREMIERE

“Stella Dallas is not only one of the first films to examine the conflict between a woman’s public role and her personal desires, it is also an early movie depiction of class barriers in the supposedly classless American society.” Monica Nolan, essay for the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, 2012

The story is simple. The daughter of a factory worker, Stella marries above her station, attempts to fit in with the upper crust, but is betrayed by her preference for beer, feathered hats, and practical jokes. At this point, her marriage to Stephen Dallas exists only in name, as the mismatched couple have separated. The only evidence of their brief union is daughter Laurel, who inherits her father’s refinement but lives with her vulgar mother. And therein lies the tragedy—Stella adores her daughter but is unwittingly damaging her, exhaling a cloud of bad taste that poisons her daughter’s future like secondhand smoke. In the twisted logic of the movie’s day, Stella is the problem, not the snobbery of the upper class. Stella must give up her only child to save her.

Introduced by Barrie Pattison at Ritz Cinemas and by Jake Wilson at Lido Cinemas

The film will be presented accompanied by a soundtrack featuring a new orchestral score composed by Stephen Horne and recorded at the film’s 2021 restoration premiere at the Venice Biennale.

“Stella Dallas is not only one of the first films to examine the conflict between a woman’s public role and her personal desires, it is also an early movie depiction of class barriers in the supposedly classless American society.” Monica Nolan, essay for the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, 2012

The story is simple. The daughter of a factory worker, Stella marries above her station, attempts to fit in with the upper crust, but is betrayed by her preference for beer, feathered hats, and practical jokes. At this point, her marriage to Stephen Dallas exists only in name, as the mismatched couple have separated. The only evidence of their brief union is daughter Laurel, who inherits her father’s refinement but lives with her vulgar mother. And therein lies the tragedy—Stella adores her daughter but is unwittingly damaging her, exhaling a cloud of bad taste that poisons her daughter’s future like secondhand smoke. In the twisted logic of the movie’s day, Stella is the problem, not the snobbery of the upper class. Stella must give up her only child to save her.

Introduced by Barrie Pattison at Ritz Cinemas and by Jake Wilson at Lido Cinemas

The film will be presented accompanied by a soundtrack featuring a new orchestral score composed by Stephen Horne and recorded at the film’s 2021 restoration premiere at the Venice Biennale.

FILM NOTES

By Jane Mills

By Jane Mills

Jane Mills (UNSW) loves being a part of Cinema Reborn.

HENRY KING

‘What a picture! “Stella Dallas”, Samuel Goldwyn’s first release through United Artists is truly a masterpiece. We unqualifiedly believe it to be one of the finest pictures ever produced. Frankly we doubt it has ever been equalled and are sure it has never been surpassed in the tremendous sweep of its emotional appeal and the poignancy of its soul-stirring drama of mother-love and sacrifice.’ C.S. Sewell (1)

Henry King (1886-1982) must be considered one of the great Hollywood directors but he hasn’t always been on lists of all-time greats, as film curator Peter von Bagh writes:

‘Henry King’s name is seldom mentioned among the masters whose positions are fixed on the world map of the cinema like continents: John Ford, Raoul Walsh, Allan Dwan, et cetera. We have been accustomed to see King as a typical contract worker [for the studio system] and that, indeed, is what he was.’ (2)

He was much more than that.

Initially an actor and director in local repertory theatre in his home state of Virginia, King began his cinema career as an actor in 1912. After a spell of screenwriting and set designing, he directed his first film in 1916. He went on to become one of the most commercially successful Hollywood directors of the 1920s and '30s, widely respected for discovering, or making stars of, Baby Marie Osborne (one of Hollywood’s first child stars), Ronald Colman, Tyrone Power, Jennifer Jones and Gregory Peck.

In a career spanning silents and talkies, mostly working within the Hollywood studio system, by the time he directed his last film, Tender is the Night (1962), he had directed 116 films, acted in 117, produced 12 and edited one. He was twice nominated for Best Director Oscar (The Song of Bernadette (1943) and Wilson (1944)), directed seven films nominated for the Best Picture Oscar, and awarded the first Golden Globe Award for Best Director for The Song of Bernadette. His films regularly won fanzine “best film of the year” accolades and were admired by fellow filmmakers. Mary Pickford named one of his most celebrated films, Tol’able David (1921), starring Richard Barthelmess, as her all-time favourite, and Henry Ford included both Bernadette and Tol’able David in his top ten best films. The great Soviet filmmaker and theorist, V.I. Pudovkin, praised King for his editing skill and for teaching him techniques for achieving narrative economy, such as how to encapsulate a character in four simple shots. (The shot in Stella Dallas where we learn why and how a character dies is an excellent example of King’s narrative economy). King was also one of the founders of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

While many of his films were wildly praised when released, King’s reputation took a dive in his later years. US film curator and critic Dave Kehr wrote of Pudovkin’s ‘unaccountable enthusiasm’ for Tol‘able David but conceded: ‘as academic classics go it’s not all that bad. Henry King’s direction owes everything to Griffith, which helps, but even D.W. wouldn’t have permitted himself a biblical allegory as painful as this one.’ (3) King’s Love is a Many-Splendored Thing (1955), starring William Holden and Jennifer Jones (playing a Eurasian in yellow face), that Variety found ‘beautiful, absorbing’, was nominated for eight Oscars (winning three), and won the Photoplay Gold Medal; for Kehr it was ‘the quintessence of a certain kind of ‘50s schlock.’ The film historian, David Thomson, wrote of King’s inability to ‘infuse narrative with life or any recognizable style,’ and ‘a fatal slowness.’ (4) The proponent of the auteur theory of criticism, Andrew Sarris, was crueller, writing of several of King’s best admired films (including Stella Dallas) as being ‘likable enough in their plodding intensity, but not quite forceful enough to compensate for the endless footage of studio-commissioned slop which King could never convert into anything personal or even entertaining ... even at his best, King tended to be turgid and rhetorical in his storytelling style.’ (5) For Sarris and other critics, a significant “problem” with King’s films was that they could discern no “auteurist” signs or themes. Film historian Ed Buscombe concurred: ‘King never had a really identifiable style or theme as a director.’ (6)

The sheer quantity of the films King made under the Hollywood studio system, mostly for Fox, then Twentieth Century Fox, and the ease, indeed the pleasure, he appeared to take in working with the scripts, sets, and actors he was given under this system, may account for the critical disparagement. The number of genres he produced also earned him dismissive scorn: woman’s weepie, western, romance, adventure, biopic, action, religious invocation, melodrama, period drama, psychological western and gunfighter film. King probably made at least one film in (almost) any genre you care to mention. He likely did himself no favours when he summed up his filmmaking approach thus: ‘Professionalism means the art of delivering the text or giving form to a scene without getting moved at all by the text or the scene’ (cited in Bagh). Nor would he have endeared himself to the auteurist critics by declaring: ‘When direction shows, it's bad.’ The main “problem”, of course, may lie with those critics who insist upon an auterist signature as the sign of a great, even a good, filmmaker.

As so often in film history, attitudes and tastes change and King’s reputation slowly recovered. In the mid-‘70s, New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) praised his versatility and screened a retrospective of his films, issuing a press release that discussed his style as ‘essentially that of a storyteller’ – ‘[a style that] has been described as direct and unobtrusive, though each of his pictures bears the stamp of his own pace – partly because King has always stressed the importance of editing. The great Russian director Pudovkin long ago pointed out the excellence of King's montage work ...’ (7).

By 2006, film writer Mario Reading valued King as: ‘an extraordinarily versatile studio director of the old school … he entertained untold millions with such high-quality and intelligently thought-out star vehicles as Tol’able David (1921), State Fair (1933), the exquisitely photographed Jesse James (1939), and the excellent, and still underrated The Sun Also Rises (1958). King loved America, and his best films are imbued with a sense of its possibilities, thus making him a rare optimist in a film world populated largely by would-be cynics.’ (8).

In 2008, even David Thomson was prepared to reassess King, now describing Tol’able David as ‘one of the most spectacular and heartfelt identifications with countryside ever managed onscreen.’ Thomson found its influence ‘in just about every [subsequent] film where revenge has rectitude’ – mentioning, especially, High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1952) and Straw Dogs (Sam Peckinpah, 1971). High praise indeed.

For Cinema Reborn audiences perhaps the highest honour that can be paid to a director was the retrospective awarded him in 2019 at the Il Cinema Ritrovato Festival. In the festival’s brochure, Bagh, a former Ritrovato Festival Artistic Director, wrote a warm, balanced appreciation of King: ‘In public awareness [he] has languished far from his rightful place of honor with the great masters ... When the full terrain is difficult to fathom, pearls remain buried. (9) Nevertheless, Bagh agrees that King made some clunkers: ‘All in all King’s œuvre was exceptionally bountiful even on a Hollywood scale. Quantity tended to replace quality especially at the beginning and end of his career.’ Looking more closely at his so-called “failed” movies, Bagh finds ‘interconnected syntheses and thematic arches, not so much between works but between images that enter into dialogue even when there are as many as six quickly manufactured films in between. Often in the background of such connections one can detect the director’s affinity for subjects important to him.’

King is now valued for his skill in portraying illusion and disillusion and the relationship between them. We see it clearly in his melodrama masterpiece, Stella Dallas (1925). For many years it was compared unfavourably with the 1937 adaptation starring Barbara Stanwyck and became almost forgotten. Stanwyck is indeed brilliant, but in King’s wildly popular silent version, this compelling story of mother-daughter love and maternal sacrifice – ‘a subject all too familiar for Americans’, as Bagh writes – ‘was treated more maturely and courageously than in Vidor’s sound remake.’

Henry King (1886-1982) must be considered one of the great Hollywood directors but he hasn’t always been on lists of all-time greats, as film curator Peter von Bagh writes:

‘Henry King’s name is seldom mentioned among the masters whose positions are fixed on the world map of the cinema like continents: John Ford, Raoul Walsh, Allan Dwan, et cetera. We have been accustomed to see King as a typical contract worker [for the studio system] and that, indeed, is what he was.’ (2)

He was much more than that.

Initially an actor and director in local repertory theatre in his home state of Virginia, King began his cinema career as an actor in 1912. After a spell of screenwriting and set designing, he directed his first film in 1916. He went on to become one of the most commercially successful Hollywood directors of the 1920s and '30s, widely respected for discovering, or making stars of, Baby Marie Osborne (one of Hollywood’s first child stars), Ronald Colman, Tyrone Power, Jennifer Jones and Gregory Peck.

In a career spanning silents and talkies, mostly working within the Hollywood studio system, by the time he directed his last film, Tender is the Night (1962), he had directed 116 films, acted in 117, produced 12 and edited one. He was twice nominated for Best Director Oscar (The Song of Bernadette (1943) and Wilson (1944)), directed seven films nominated for the Best Picture Oscar, and awarded the first Golden Globe Award for Best Director for The Song of Bernadette. His films regularly won fanzine “best film of the year” accolades and were admired by fellow filmmakers. Mary Pickford named one of his most celebrated films, Tol’able David (1921), starring Richard Barthelmess, as her all-time favourite, and Henry Ford included both Bernadette and Tol’able David in his top ten best films. The great Soviet filmmaker and theorist, V.I. Pudovkin, praised King for his editing skill and for teaching him techniques for achieving narrative economy, such as how to encapsulate a character in four simple shots. (The shot in Stella Dallas where we learn why and how a character dies is an excellent example of King’s narrative economy). King was also one of the founders of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

While many of his films were wildly praised when released, King’s reputation took a dive in his later years. US film curator and critic Dave Kehr wrote of Pudovkin’s ‘unaccountable enthusiasm’ for Tol‘able David but conceded: ‘as academic classics go it’s not all that bad. Henry King’s direction owes everything to Griffith, which helps, but even D.W. wouldn’t have permitted himself a biblical allegory as painful as this one.’ (3) King’s Love is a Many-Splendored Thing (1955), starring William Holden and Jennifer Jones (playing a Eurasian in yellow face), that Variety found ‘beautiful, absorbing’, was nominated for eight Oscars (winning three), and won the Photoplay Gold Medal; for Kehr it was ‘the quintessence of a certain kind of ‘50s schlock.’ The film historian, David Thomson, wrote of King’s inability to ‘infuse narrative with life or any recognizable style,’ and ‘a fatal slowness.’ (4) The proponent of the auteur theory of criticism, Andrew Sarris, was crueller, writing of several of King’s best admired films (including Stella Dallas) as being ‘likable enough in their plodding intensity, but not quite forceful enough to compensate for the endless footage of studio-commissioned slop which King could never convert into anything personal or even entertaining ... even at his best, King tended to be turgid and rhetorical in his storytelling style.’ (5) For Sarris and other critics, a significant “problem” with King’s films was that they could discern no “auteurist” signs or themes. Film historian Ed Buscombe concurred: ‘King never had a really identifiable style or theme as a director.’ (6)

The sheer quantity of the films King made under the Hollywood studio system, mostly for Fox, then Twentieth Century Fox, and the ease, indeed the pleasure, he appeared to take in working with the scripts, sets, and actors he was given under this system, may account for the critical disparagement. The number of genres he produced also earned him dismissive scorn: woman’s weepie, western, romance, adventure, biopic, action, religious invocation, melodrama, period drama, psychological western and gunfighter film. King probably made at least one film in (almost) any genre you care to mention. He likely did himself no favours when he summed up his filmmaking approach thus: ‘Professionalism means the art of delivering the text or giving form to a scene without getting moved at all by the text or the scene’ (cited in Bagh). Nor would he have endeared himself to the auteurist critics by declaring: ‘When direction shows, it's bad.’ The main “problem”, of course, may lie with those critics who insist upon an auterist signature as the sign of a great, even a good, filmmaker.

As so often in film history, attitudes and tastes change and King’s reputation slowly recovered. In the mid-‘70s, New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) praised his versatility and screened a retrospective of his films, issuing a press release that discussed his style as ‘essentially that of a storyteller’ – ‘[a style that] has been described as direct and unobtrusive, though each of his pictures bears the stamp of his own pace – partly because King has always stressed the importance of editing. The great Russian director Pudovkin long ago pointed out the excellence of King's montage work ...’ (7).

By 2006, film writer Mario Reading valued King as: ‘an extraordinarily versatile studio director of the old school … he entertained untold millions with such high-quality and intelligently thought-out star vehicles as Tol’able David (1921), State Fair (1933), the exquisitely photographed Jesse James (1939), and the excellent, and still underrated The Sun Also Rises (1958). King loved America, and his best films are imbued with a sense of its possibilities, thus making him a rare optimist in a film world populated largely by would-be cynics.’ (8).

In 2008, even David Thomson was prepared to reassess King, now describing Tol’able David as ‘one of the most spectacular and heartfelt identifications with countryside ever managed onscreen.’ Thomson found its influence ‘in just about every [subsequent] film where revenge has rectitude’ – mentioning, especially, High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1952) and Straw Dogs (Sam Peckinpah, 1971). High praise indeed.

For Cinema Reborn audiences perhaps the highest honour that can be paid to a director was the retrospective awarded him in 2019 at the Il Cinema Ritrovato Festival. In the festival’s brochure, Bagh, a former Ritrovato Festival Artistic Director, wrote a warm, balanced appreciation of King: ‘In public awareness [he] has languished far from his rightful place of honor with the great masters ... When the full terrain is difficult to fathom, pearls remain buried. (9) Nevertheless, Bagh agrees that King made some clunkers: ‘All in all King’s œuvre was exceptionally bountiful even on a Hollywood scale. Quantity tended to replace quality especially at the beginning and end of his career.’ Looking more closely at his so-called “failed” movies, Bagh finds ‘interconnected syntheses and thematic arches, not so much between works but between images that enter into dialogue even when there are as many as six quickly manufactured films in between. Often in the background of such connections one can detect the director’s affinity for subjects important to him.’

King is now valued for his skill in portraying illusion and disillusion and the relationship between them. We see it clearly in his melodrama masterpiece, Stella Dallas (1925). For many years it was compared unfavourably with the 1937 adaptation starring Barbara Stanwyck and became almost forgotten. Stanwyck is indeed brilliant, but in King’s wildly popular silent version, this compelling story of mother-daughter love and maternal sacrifice – ‘a subject all too familiar for Americans’, as Bagh writes – ‘was treated more maturely and courageously than in Vidor’s sound remake.’

THE FILM

US novelist and poet Olive Higgins Prouty (1882-1974) was bemused by the long and varied life of her character, Stella Dallas, writing in her memoir: ‘the feature of most interest about Stella Dallas is, I think, the number of its reincarnations.’ (10) Prouty didn’t live long enough to meet all the reincarnations but there were already seven by the time she died. She was right about Stella’s impressive number of afterlives but, for many, very wrong about what makes her so interesting.

Stella first emerged in a 1922 magazine serialisation; within a year she had stepped into a novel; the following year she found herself in a stage play; and in 1925 she appeared in her first film adaptation. There would be two more films – King Vidor’s Stella Dallas (1937), starring Barbara Stanwyck, and John Erman’s Stella (1990), starring Bette Midler. 1937 was a busy year for Stella: she also appeared in radio adaptation, again with Stanwyck, and she began an unbelievably long career in a radio soap opera that played for fifteen minutes every night for eighteen years (1937-1955).

Understanding Stella

Nowhere have Stella’s many and varied incarnations been lived and re-lived as vigorously as in the myriad articles by film historians, theorists and critics who have discussed, argued and disagreed over her. In these texts, she is variously subversive, conforming, transgressive, acquiescent, rebellious, compliant, resistant and resourceful. (11) For some, she is many, even all, of these simultaneously.

It’s not easy to unravel Stella’s story: her many reincarnations tend to form, re-form and inform each other. In short, this is a story about a mother-daughter relationship, mother-love and sacrifice, female agency (or not), gender and class oppression, and triumphant sisterliness. To appreciate more fully the many ways in which Stella has been understood (and perhaps misunderstood), a longer synopsis is needed.

Stella Dane (Belle Bennett) is the daughter of a mill worker with little education or “refinement” but a sparkle in her eye, and lots of gutsy determination (and not a little guile) to better herself. An intertitle tells us Stella ‘traps’ the handsome, wealthy and educated Stephen into marriage but struggles to adapt to her new station in life. Oh, how she tries! But in Stephen’s eyes, she gets it wrong every time. She’s big, blowsy and loud, has execrable dress sense and is far too fond of a good time for his refined taste.

Inevitably, the marriage fails. Exasperated by his young wife’s inability to live up to the social codes and conventions he expects of a wife, Stephen goes to work and live in New York where he bumps into the love of his life, the now-widowed Helen, who is everything Stella isn’t: slim, elegant, wealthy, restrained and refined.

Stella devotes her life to bringing up her daughter Laurel by herself and she encourages Laurel to love fine things, respectable books and noble thoughts. When Laurel is a teenager, Stephen invites her to stay with him at Helen’s classy mansion and the girl is smitten by Helen and the sophisticated lifestyle to which she’s introduced. When Laurel falls in love with the wealthy Dick Grosvenor, (the 16-year-old Douglas Fairbanks Jr with a saucy, if slightly creepy, moustache), Stella is faced by a dilemma of huge proportions.

Does Laurel stay with her mother and become a mill worker, or does she live with her father and Helen, now the new Mrs Dallas, and live the life of a “lady”? With a fierce love, Stella wants only the best for Laurel and is convinced that she, Stella, can only hold her back. Her daughter’s future is something she will protect at all costs. It is, of course, Stella who will pay the cost. With the tacit connivance and sisterly solidarity of Helen, Stella resorts to a tear-tugging deception to push Laurel away so that she might better herself in the upper-middle-class society that’s closed to Stella.

Critical tussles

The questions the critics and theorists tussle over and invite us to consider include:

As a maternal melodrama or ‘woman’s weepie,’ Stella Dallas squarely hits the spot. Grown men have been known to shed a tear watching Stella stand in the rain and dark watching her darling daughter definitively leave her and her working-class background as she is transported into upper-middle-class bliss. Stella is, like us the audience —so near and yet so far. Legend has it that producer Samuel Goldwyn cried every time he saw this final scene. It was a film he liked so much that he made it again in 1937, as Stella’s second film reincarnation.

Conclusion:

These notes start with the opening paragraph in C.S. Sewell’s contemporary review that possibly crosses the line from considered critique to adulation. His closing sentiments, however, I completely share:

‘There are few so blasé that they won’t feel a tug at the heart, a lump in the throat and moist eyelids while viewing “Stella Dallas”… Its appeal is elemental and universal, for the mother’s sacrifice can be understood and appreciated by all classes. Women will rave over it and men, too, will feel its tremendous force. “Stella Dallas” is truly a masterpiece.’

Notes

Stella first emerged in a 1922 magazine serialisation; within a year she had stepped into a novel; the following year she found herself in a stage play; and in 1925 she appeared in her first film adaptation. There would be two more films – King Vidor’s Stella Dallas (1937), starring Barbara Stanwyck, and John Erman’s Stella (1990), starring Bette Midler. 1937 was a busy year for Stella: she also appeared in radio adaptation, again with Stanwyck, and she began an unbelievably long career in a radio soap opera that played for fifteen minutes every night for eighteen years (1937-1955).

Understanding Stella

Nowhere have Stella’s many and varied incarnations been lived and re-lived as vigorously as in the myriad articles by film historians, theorists and critics who have discussed, argued and disagreed over her. In these texts, she is variously subversive, conforming, transgressive, acquiescent, rebellious, compliant, resistant and resourceful. (11) For some, she is many, even all, of these simultaneously.

It’s not easy to unravel Stella’s story: her many reincarnations tend to form, re-form and inform each other. In short, this is a story about a mother-daughter relationship, mother-love and sacrifice, female agency (or not), gender and class oppression, and triumphant sisterliness. To appreciate more fully the many ways in which Stella has been understood (and perhaps misunderstood), a longer synopsis is needed.

Stella Dane (Belle Bennett) is the daughter of a mill worker with little education or “refinement” but a sparkle in her eye, and lots of gutsy determination (and not a little guile) to better herself. An intertitle tells us Stella ‘traps’ the handsome, wealthy and educated Stephen into marriage but struggles to adapt to her new station in life. Oh, how she tries! But in Stephen’s eyes, she gets it wrong every time. She’s big, blowsy and loud, has execrable dress sense and is far too fond of a good time for his refined taste.

Inevitably, the marriage fails. Exasperated by his young wife’s inability to live up to the social codes and conventions he expects of a wife, Stephen goes to work and live in New York where he bumps into the love of his life, the now-widowed Helen, who is everything Stella isn’t: slim, elegant, wealthy, restrained and refined.

Stella devotes her life to bringing up her daughter Laurel by herself and she encourages Laurel to love fine things, respectable books and noble thoughts. When Laurel is a teenager, Stephen invites her to stay with him at Helen’s classy mansion and the girl is smitten by Helen and the sophisticated lifestyle to which she’s introduced. When Laurel falls in love with the wealthy Dick Grosvenor, (the 16-year-old Douglas Fairbanks Jr with a saucy, if slightly creepy, moustache), Stella is faced by a dilemma of huge proportions.

Does Laurel stay with her mother and become a mill worker, or does she live with her father and Helen, now the new Mrs Dallas, and live the life of a “lady”? With a fierce love, Stella wants only the best for Laurel and is convinced that she, Stella, can only hold her back. Her daughter’s future is something she will protect at all costs. It is, of course, Stella who will pay the cost. With the tacit connivance and sisterly solidarity of Helen, Stella resorts to a tear-tugging deception to push Laurel away so that she might better herself in the upper-middle-class society that’s closed to Stella.

Critical tussles

The questions the critics and theorists tussle over and invite us to consider include:

- Is Stella a good, bad or even a “good enough” mother?

- Does Stella want to be “something else besides a mother” – and does she achieve this? (12)

- Does she “become” a mother only when she loses her daughter? (13)

- By her act of maternal sacrifice, is Stella challenging patriarchal norms for the role of women or is she simply conforming?

- What does the covenant of solidarity between the big, blowsy, Stella (Belle Bennett reportedly gained several pounds for the part) and the slender, refined and restrained Helen tell us about attitudes towards social class, taste and feminism in 1920s America?

- Is Stella’s taste in clothes and books (she prefers Elinor Glyn to George Bernard Shaw) a sign of innate “ill-breeding,” or Stella’s way of telling bourgeois society to get stuffed?

- Is the film a powerful indictment of the rigid class barriers in prosperous, postwar 1920s America or does it endorse the inevitability of such barriers?

- To what extent did the categorisation of the film as a “women’s weepie” (a term critic Molly Haskell described as one of ‘critical opprobrium’, carrying the ‘implication that women, and therefore women’s emotional problems, are of minor significance’) damage the film and King’s reputation? (14)

- Does the final shot of Stella function to efface Stella even as it glorifies her sacrificial act of motherly love?

- Is Stella finally cowed or triumphant?

As a maternal melodrama or ‘woman’s weepie,’ Stella Dallas squarely hits the spot. Grown men have been known to shed a tear watching Stella stand in the rain and dark watching her darling daughter definitively leave her and her working-class background as she is transported into upper-middle-class bliss. Stella is, like us the audience —so near and yet so far. Legend has it that producer Samuel Goldwyn cried every time he saw this final scene. It was a film he liked so much that he made it again in 1937, as Stella’s second film reincarnation.

Conclusion:

These notes start with the opening paragraph in C.S. Sewell’s contemporary review that possibly crosses the line from considered critique to adulation. His closing sentiments, however, I completely share:

‘There are few so blasé that they won’t feel a tug at the heart, a lump in the throat and moist eyelids while viewing “Stella Dallas”… Its appeal is elemental and universal, for the mother’s sacrifice can be understood and appreciated by all classes. Women will rave over it and men, too, will feel its tremendous force. “Stella Dallas” is truly a masterpiece.’

Notes

- C.S. Sewell, ‘Through the Box Office Window: Stella Dallas; Samuel Goldwyn Picture One of Finest Ever Made, is Truly a Dramatic and Emotional Masterpiece.’ The Moving Picture World. 77 (4), Nov 28, 1925.

- Peter von Bagh, ‘Beyond the American Dream’, https://mubi.com/en/notebook/posts/henry-king-beyond-the-american-dream

- https://chicagoreader.com/film-tv/tolable-david/

- David Thomson, A Biographical Dictionary of Film (Welbeck Publishing Group, 1994).

- Andrew Sarris, American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968 (Da Capo Press, 1969.

- Edward Buscombe, in Steven Jay Schneider (Ed.) 501 Movie Directors, (B.E.S. Pub & Co.), (2007).

- https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/press_archives/5626/releases/MOMA_1978_0062_57.pdf

- Mario Reading, The Movie Companion (Constable & Robinson, 2006).

- https://mubi.com/en/notebook/posts/henry-king-beyond-the-american-dream

- Pencil Shavings (Riverside Press, 1961). T https://openlibrary.org/authors/OL405101A/Olive_Higgins_Prouty

- I am indebted to feminist and other film theorists who have participated in discussion of the various Stella Dallas incarnations, including: Molly Haskell, Linda Williams, E. Ann Kaplan, Stanley Cavell, Patrice Petro and Carol Flinn, Christine Gledhill, Lucy Fisher, Jennifer Parchesky, Kristy Branham, Kathleen McHugh, Jeanine Basinger, Joan Copjec.

- The phrase is that of Linda Williams, ‘“Something Else Besides a Mother”. Stella Dallas and the Maternal Melodrama’, In Christine Gledhill, (ed.), Home is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama and the Woman's Film, (British Film Institute, 1987).

- Stanley Cavell, The Hollywood Drama of the Unknown Woman (University of Chicago Press, 1997).

- Molly Haskell, From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies, (University of Chicago Press, 1974).

- For complete screenplay: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Stella_Dallas_(1925_film)#bodyContent

THE RESTORATION

Source: DCP Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art New York

Digital restoration by the Museum of Modern Art and the Film Foundation, from a 35mm print held by MoMA, with support from The George Lucas Family Foundation. Accompanied by a new orchestral score composed by Stephen Horne and recorded at the film’s 2021 restoration premiere at the Venice Biennale.

Director: Henry King; Production Company: Samuel Goldwyn Productions; Producer: Samuel Goldwyn; Script: Frances Marion based on the novel by Olive Higgins Prouty; Photography: Arthur Edeson; Editor: Stuart Heisler; Wardrobe: Sophie Wachner; Original music: Herman Rosen; Restoration music: Stephen Horne.

Cast: Belle Bennett (Stella Martin/Dallas); Ronald Colman (Stephen Dallas); Jean Hersholt, (Ed Munn); Lois Moran (Laurel Dallas); Alice Joyce Helen Dane/Morrison/Dallas); Douglas Fairbanks Jr (Richard Grosvenor); Vera Lewis (Miss Philiburn); Beatrix Prior (Mrs Grosvenor).

USA | 1925 | 110 mins | B&W tinted | Silent with English intertitles and recorded score | PG

Digital restoration by the Museum of Modern Art and the Film Foundation, from a 35mm print held by MoMA, with support from The George Lucas Family Foundation. Accompanied by a new orchestral score composed by Stephen Horne and recorded at the film’s 2021 restoration premiere at the Venice Biennale.

Director: Henry King; Production Company: Samuel Goldwyn Productions; Producer: Samuel Goldwyn; Script: Frances Marion based on the novel by Olive Higgins Prouty; Photography: Arthur Edeson; Editor: Stuart Heisler; Wardrobe: Sophie Wachner; Original music: Herman Rosen; Restoration music: Stephen Horne.

Cast: Belle Bennett (Stella Martin/Dallas); Ronald Colman (Stephen Dallas); Jean Hersholt, (Ed Munn); Lois Moran (Laurel Dallas); Alice Joyce Helen Dane/Morrison/Dallas); Douglas Fairbanks Jr (Richard Grosvenor); Vera Lewis (Miss Philiburn); Beatrix Prior (Mrs Grosvenor).

USA | 1925 | 110 mins | B&W tinted | Silent with English intertitles and recorded score | PG