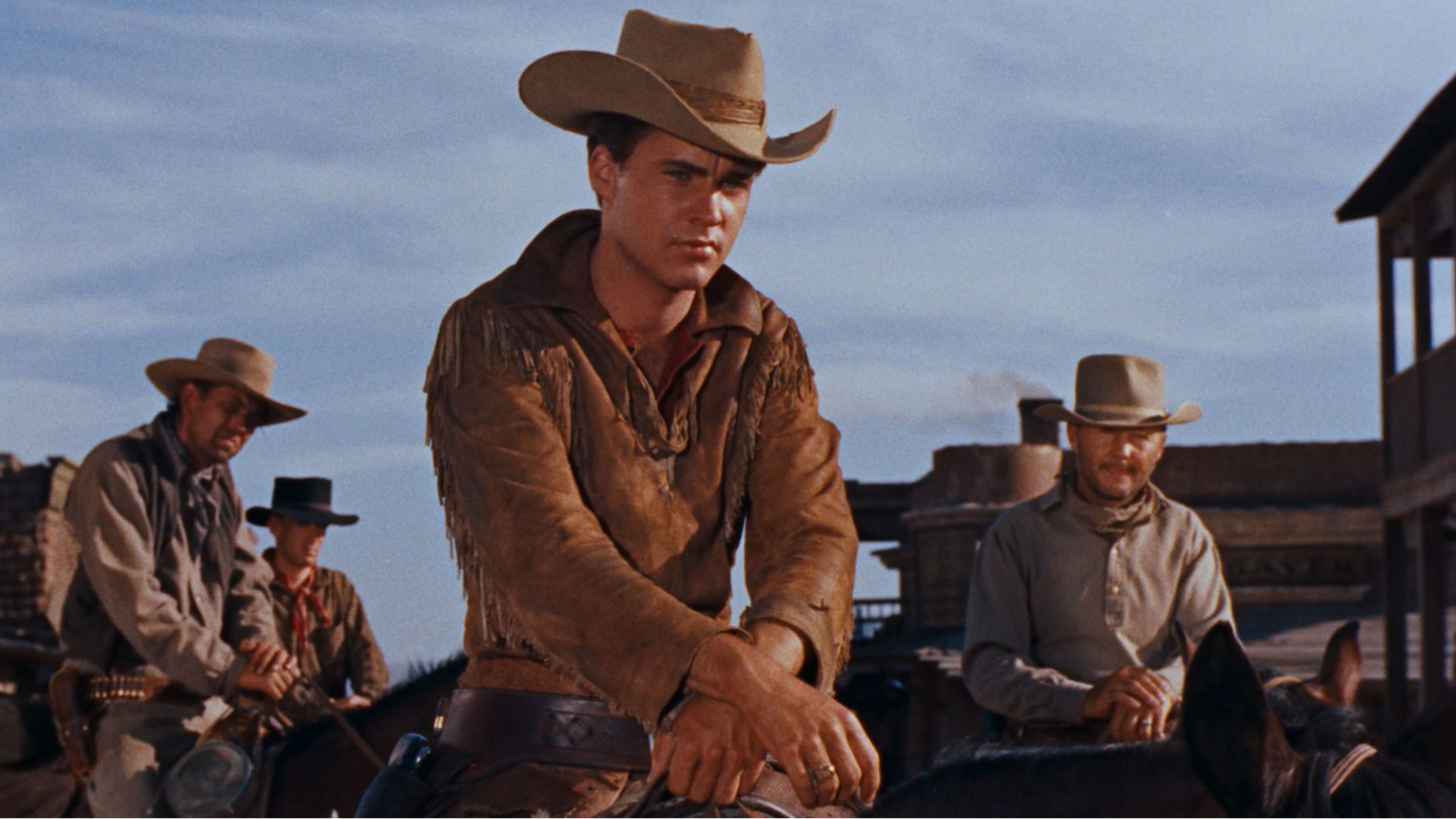

RIO BRAVO (1959)

![]()

Randwick Ritz, Sydney:

08:15 PM, Thursday

May 02

02:00PM, Friday

May 03

Lido Cinemas, Melbourne:

03:30 PM, Friday

May 10

08:10 PM, Tuesday

May 14

Rating: PG

Duration:141 minutes

Country: United States

Language: English

Cast: John Wayne, Dean Martin, Ricky Nelson, Walter Brennan, Angie Dickinson

Director: Howard Hawks

SYDNEY TICKETS ⟶

MELBOURNE TICKETS ⟶

08:15 PM, Thursday

May 02

02:00PM, Friday

May 03

Lido Cinemas, Melbourne:

03:30 PM, Friday

May 10

08:10 PM, Tuesday

May 14

Rating: PG

Duration:141 minutes

Country: United States

Language: English

Cast: John Wayne, Dean Martin, Ricky Nelson, Walter Brennan, Angie Dickinson

Director: Howard Hawks

SYDNEY TICKETS ⟶

MELBOURNE TICKETS ⟶

4K RESTORATION – AUSTRALIAN PREMIERE

“If I had to choose a film that would justify the existence of Hollywood, I think it would be Rio Bravo” – Robin Wood

“A masterpiece among Westerns”– Molly Haskell

Sheriff John Chance (John Wayne) holds a killer in jail and waits for a United States Marshal to come to his border-town of Rio Bravo. The prisoner’s family and hired guns start besieging the town and the jail. Chance’s helpers are his ex-deputy Dude (Dean Martin), now the town drunk; a cantankerous old cripple Stumpy (Walter Brennan); a young hotshot gunfighter Colorado (Ricky Nelson); and a passing gambler known as Feathers (Angie Dickinson). One of the most beloved of all Westerns, Rio Bravo was so successful at the box office, Howard Hawks directed two further revisions of the same story (El Dorado and Rio Lobo). It's based in a small town in the West after the pioneers have left – all stagecoaches, hotel owners, sheriffs, deputies, farmers, gamblers and hired guns. This 4K Ultra High-Definition restoration is from Warner Bros. in collaboration with The Film Foundation.

Introduced by Claude Gonzalez at Ritz Cinemas and Eloise Ross at Lido Cinemas.

“To watch Rio Bravo is to see a master craftsman at work. The film is seamless. There is not a shot that is wrong. It is uncommonly absorbing, and the 141 minutes running time flows past like running water.” – Roger Ebert

“The real revelation, however, is Dean Martin, in a part he obviously understood well. His role as the drunken deputy who redeems himself is crucial to the film and the singer-actor handles his part with skill.” – Virgin Film Guide

“It’s the sort of film, in David Thomson’s words, which reveals that ‘men are more expressive rolling a cigarette than saving the world.’” – Geoff Andrew

This programme is presented with the generous support of John and Hazel Sullivan.

“If I had to choose a film that would justify the existence of Hollywood, I think it would be Rio Bravo” – Robin Wood

“A masterpiece among Westerns”– Molly Haskell

Sheriff John Chance (John Wayne) holds a killer in jail and waits for a United States Marshal to come to his border-town of Rio Bravo. The prisoner’s family and hired guns start besieging the town and the jail. Chance’s helpers are his ex-deputy Dude (Dean Martin), now the town drunk; a cantankerous old cripple Stumpy (Walter Brennan); a young hotshot gunfighter Colorado (Ricky Nelson); and a passing gambler known as Feathers (Angie Dickinson). One of the most beloved of all Westerns, Rio Bravo was so successful at the box office, Howard Hawks directed two further revisions of the same story (El Dorado and Rio Lobo). It's based in a small town in the West after the pioneers have left – all stagecoaches, hotel owners, sheriffs, deputies, farmers, gamblers and hired guns. This 4K Ultra High-Definition restoration is from Warner Bros. in collaboration with The Film Foundation.

Introduced by Claude Gonzalez at Ritz Cinemas and Eloise Ross at Lido Cinemas.

“To watch Rio Bravo is to see a master craftsman at work. The film is seamless. There is not a shot that is wrong. It is uncommonly absorbing, and the 141 minutes running time flows past like running water.” – Roger Ebert

“The real revelation, however, is Dean Martin, in a part he obviously understood well. His role as the drunken deputy who redeems himself is crucial to the film and the singer-actor handles his part with skill.” – Virgin Film Guide

“It’s the sort of film, in David Thomson’s words, which reveals that ‘men are more expressive rolling a cigarette than saving the world.’” – Geoff Andrew

This programme is presented with the generous support of John and Hazel Sullivan.

FILM NOTES

HOWARD HAWKS

By Digby Houghton

By Digby Houghton

Howard Hawks (1896-1979) was a tough-knuckled American director who made movies centred on chivalry, masculinity and the moral binary of good and evil. Hawks studied mechanical engineering at Cornell University before serving as a lieutenant in the Aviation Section of the Army Air Corps during World War 1. This provided him first-hand experience of the horrors of war and the trappings of masculinity.

During the war Hawks began working as an assistant for the silent film legend, Cecil B. DeMille, on a romantic war film, The Little American (1917). This experience proved beneficial when he directed his own projects, like his directorial debut, The Road to Glory (1926). Hawks’ films often featured tough-talking women, leading people to use the term “Hawksian woman” for characters played by the likes of Lauren Bacall and Katherine Hepburn, who exerted confidence, speaking their mind and parlaying with their male counterparts in witty banter.

Hawks traversed genres with ease and ingenuity like a tight-rope walker, earning him the label of ‘auteur’ from his French counterparts. Hawks made 40 films, including westerns (Red River, 1948), war films (Air Force, 1943), films noirs (The Big Sleep, 1946), gangster films (Scarface, 1932) and screwball comedies (His Girl Friday, 1940), yet the imprint of his underlying stylistic traits were still present across this scattering of different genres. Throughout the 1960s Hawks’ name served as a hyphenate with Alfred Hitchcock, used synonymously with the group known as the “Young Turks.” This group consisted of film critics from Cahiers du Cinéma, like Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, who self-identified as the ‘Hitchcocko-Hawksians’ (in contrast with the critics of their left-leaning rivalry magazine in Lyon, Positif). The label served to demonstrate the group’s adoration of Hollywood and their focus on the director.

During the war Hawks began working as an assistant for the silent film legend, Cecil B. DeMille, on a romantic war film, The Little American (1917). This experience proved beneficial when he directed his own projects, like his directorial debut, The Road to Glory (1926). Hawks’ films often featured tough-talking women, leading people to use the term “Hawksian woman” for characters played by the likes of Lauren Bacall and Katherine Hepburn, who exerted confidence, speaking their mind and parlaying with their male counterparts in witty banter.

Hawks traversed genres with ease and ingenuity like a tight-rope walker, earning him the label of ‘auteur’ from his French counterparts. Hawks made 40 films, including westerns (Red River, 1948), war films (Air Force, 1943), films noirs (The Big Sleep, 1946), gangster films (Scarface, 1932) and screwball comedies (His Girl Friday, 1940), yet the imprint of his underlying stylistic traits were still present across this scattering of different genres. Throughout the 1960s Hawks’ name served as a hyphenate with Alfred Hitchcock, used synonymously with the group known as the “Young Turks.” This group consisted of film critics from Cahiers du Cinéma, like Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, who self-identified as the ‘Hitchcocko-Hawksians’ (in contrast with the critics of their left-leaning rivalry magazine in Lyon, Positif). The label served to demonstrate the group’s adoration of Hollywood and their focus on the director.

THE FILM

By Adrian Martin

By Adrian Martin

For a cinephile, there can be no sweeter or more glorious moment in recent memory than the scene in Víctor Erice’s Cerrar los ojos (2023) when an ageing filmmaker accepts the gift of an acoustic guitar and instantly serenades his friends with a near-faultless rendition of ‘My Rifle, My Pony and Me’ – a ritual they have obviously enjoyed many times previously. Just as they have, no doubt, together watched the movie it comes from, Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo, many times previously.

Nowadays, critics of film, literature and music love to evoke the concept of late style – that moment in an artist’s trajectory when he or she has nothing left to prove, when they can go for broke, or simply do whatever they like. Luis Buñuel, Manoel de Oliveira, Agnès Varda and Clint Eastwood are among those film directors who managed to arrive at such a pinnacle of insouciant creativity. But late style sometimes triumphed even at the heart of Hollywood’s studio system, and Rio Bravo is the proof of that. Hawks had enjoyed a long, illustrious and mostly commercially successful career since the 1920s. In 1959, he was 63 years old. His road was far from over – five further features followed, including two shameless variations on Rio Bravo, and he lived to the age of 81 – but ’59 marked the moment when he truly relaxed into enjoying himself as a filmmaker.

Rio Bravo is what is known today as a hangout movie. Tarantino and P.T. Anderson, among many others, have reached for this Nirvana, but few get even half-way there. What do the characters in Rio Bravo do? For long, precious passages (it’s 141 minutes long!), they just spend time with each other: talking, teasing, laughing, singing. They constitute (as the film itself proudly declares) a motley crew of law enforcers: an old guy with a limp (Walter Brennan), an alcoholic named Dude (Dean Martin), a rookie (Ricky Nelson), and the one incontrovertible hero-figure, John T. Chance (John Wayne). Along with, in a splendid plot tangent, a feisty woman (Angie Dickinson), able to flummox Chance in any situation. Rio Bravo is a film full of delightful tangents.

Of course, there is a plot pretext binding these characters together, enforcing (in a sense) their hanging out. And that pretext – the slow encroachment of a villainous gang upon the jail that houses one of their own, and that our heroes must guard – has its own filigree of tension and suspense, coaxed along by a superb degüello composed by Dimitri Tiomkin (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AR-KbvXvBd8). In the macho, homage-crazy hands of a John Carpenter (Assault on Precinct 13, 1976), that premise is turned into full-throttle, bloody action. Hawks’ instincts, however, go elsewhere: to the redemptive arc of Dude beating the bottle (‘Didn’t spill a drop’), to a jolly game of hurling dynamite at the bad guys … and to that immortal round of communal singing (which also features ‘Get Along Home, Cindy’).

Just like for those folks around the table in Cerrar los ojos, Rio Bravo is a classic that – across time, across many different viewings in diverse times and places – weaves its way into the sentimental memories of many cinephiles. It certainly has worked that way for me. It was among my early-teenage cinema revelations, first glimpsed on the family’s black-and-white TV set. Later, it became a tug-of-war token in the film theory wars of the 1970s: were you for or against the “classical Hollywood fantasy” of Rio Bravo? Mellower times allowed for its rediscovery. Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen placed it high on their lists of the Ten Best Westerns. Critics as different as Robin Wood and Serge Daney – both militantly gay – worshipped (and wrote copiously about) it. Young “video essayists” such as Will DiGravio today devote their rapt attention to its every detail.

And I have a special memory, tied to what must have been the final projection of the extant print of Rio Bravo in Melbourne – at an outer-suburban matinee for little kids! It was, to put it mildly, not an ideal condition for the contemplative appreciation of this masterpiece: the children who were there got bored and started racing around the theatre screaming within the first five minutes. And at intermission (remember, this is a long film), they simply cleared out for good. Except for one very gentle lad who came up to me and meekly asked: ‘Mister, do you like this film?’ ‘Yes’, I replied, ‘I sure do!’ And then, after not many more words, he quietly sat beside me for the second half of the screening – Rio Bravo in 35mm, just for the two of us! And when it ended, this boy bid me a courteous farewell, and duly rejoined his mother waiting at the entrance of the cinema.

I wonder: is that child today sitting around a table, strumming a guitar and singing ‘My Rifle, My Pony and Me’ to his grown-up companions?

Nowadays, critics of film, literature and music love to evoke the concept of late style – that moment in an artist’s trajectory when he or she has nothing left to prove, when they can go for broke, or simply do whatever they like. Luis Buñuel, Manoel de Oliveira, Agnès Varda and Clint Eastwood are among those film directors who managed to arrive at such a pinnacle of insouciant creativity. But late style sometimes triumphed even at the heart of Hollywood’s studio system, and Rio Bravo is the proof of that. Hawks had enjoyed a long, illustrious and mostly commercially successful career since the 1920s. In 1959, he was 63 years old. His road was far from over – five further features followed, including two shameless variations on Rio Bravo, and he lived to the age of 81 – but ’59 marked the moment when he truly relaxed into enjoying himself as a filmmaker.

Rio Bravo is what is known today as a hangout movie. Tarantino and P.T. Anderson, among many others, have reached for this Nirvana, but few get even half-way there. What do the characters in Rio Bravo do? For long, precious passages (it’s 141 minutes long!), they just spend time with each other: talking, teasing, laughing, singing. They constitute (as the film itself proudly declares) a motley crew of law enforcers: an old guy with a limp (Walter Brennan), an alcoholic named Dude (Dean Martin), a rookie (Ricky Nelson), and the one incontrovertible hero-figure, John T. Chance (John Wayne). Along with, in a splendid plot tangent, a feisty woman (Angie Dickinson), able to flummox Chance in any situation. Rio Bravo is a film full of delightful tangents.

Of course, there is a plot pretext binding these characters together, enforcing (in a sense) their hanging out. And that pretext – the slow encroachment of a villainous gang upon the jail that houses one of their own, and that our heroes must guard – has its own filigree of tension and suspense, coaxed along by a superb degüello composed by Dimitri Tiomkin (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AR-KbvXvBd8). In the macho, homage-crazy hands of a John Carpenter (Assault on Precinct 13, 1976), that premise is turned into full-throttle, bloody action. Hawks’ instincts, however, go elsewhere: to the redemptive arc of Dude beating the bottle (‘Didn’t spill a drop’), to a jolly game of hurling dynamite at the bad guys … and to that immortal round of communal singing (which also features ‘Get Along Home, Cindy’).

Just like for those folks around the table in Cerrar los ojos, Rio Bravo is a classic that – across time, across many different viewings in diverse times and places – weaves its way into the sentimental memories of many cinephiles. It certainly has worked that way for me. It was among my early-teenage cinema revelations, first glimpsed on the family’s black-and-white TV set. Later, it became a tug-of-war token in the film theory wars of the 1970s: were you for or against the “classical Hollywood fantasy” of Rio Bravo? Mellower times allowed for its rediscovery. Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen placed it high on their lists of the Ten Best Westerns. Critics as different as Robin Wood and Serge Daney – both militantly gay – worshipped (and wrote copiously about) it. Young “video essayists” such as Will DiGravio today devote their rapt attention to its every detail.

And I have a special memory, tied to what must have been the final projection of the extant print of Rio Bravo in Melbourne – at an outer-suburban matinee for little kids! It was, to put it mildly, not an ideal condition for the contemplative appreciation of this masterpiece: the children who were there got bored and started racing around the theatre screaming within the first five minutes. And at intermission (remember, this is a long film), they simply cleared out for good. Except for one very gentle lad who came up to me and meekly asked: ‘Mister, do you like this film?’ ‘Yes’, I replied, ‘I sure do!’ And then, after not many more words, he quietly sat beside me for the second half of the screening – Rio Bravo in 35mm, just for the two of us! And when it ended, this boy bid me a courteous farewell, and duly rejoined his mother waiting at the entrance of the cinema.

I wonder: is that child today sitting around a table, strumming a guitar and singing ‘My Rifle, My Pony and Me’ to his grown-up companions?

THE RESTORATION

Restored by Warner Bros. in collaboration with The Film Foundation.

Director, Producer: Howard Hawks; Production Company: Armada Productions; Script: Jules Furthman, Leigh Brackett, from the story ‘A Bull by the Tail’ by B H McCampbell ; Photography: Russell Harlan; Editor: Folmar Blangsted; Art Direction: Leo K Kuter; Set Decoration: Ralph S Hurst; Sound: Robert B Lee; Music: Dimitri Tiomkin; Costumes: Marjorie Best.

Cast: John Wayne (John T Chance), Dean Martin (Dude), Ricky Nelson (Colorado), Angie Dickinson (Feathers), Walter Brennan (Stumpy), Ward Bond (Pat Wheeler), John Russell (Nathan Burdette), Pedro Gonzalez Gonzalez (Carlos Robante), Estelita Rodriguez (Consuela Robante), Claude Akins (Joe Burdette).

USA | 1959 | 141 mins | 4K DCP | Colour | English| M

Director, Producer: Howard Hawks; Production Company: Armada Productions; Script: Jules Furthman, Leigh Brackett, from the story ‘A Bull by the Tail’ by B H McCampbell ; Photography: Russell Harlan; Editor: Folmar Blangsted; Art Direction: Leo K Kuter; Set Decoration: Ralph S Hurst; Sound: Robert B Lee; Music: Dimitri Tiomkin; Costumes: Marjorie Best.

Cast: John Wayne (John T Chance), Dean Martin (Dude), Ricky Nelson (Colorado), Angie Dickinson (Feathers), Walter Brennan (Stumpy), Ward Bond (Pat Wheeler), John Russell (Nathan Burdette), Pedro Gonzalez Gonzalez (Carlos Robante), Estelita Rodriguez (Consuela Robante), Claude Akins (Joe Burdette).

USA | 1959 | 141 mins | 4K DCP | Colour | English| M