ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST (1968)

7:45 PM, Saturday 30 April

Premiere: Introducced by Jane Mills

1:00 PM, Tuesday 03 May

Randwick Ritz

Director: Sergio Leone

Country: ITALY

Year: 1968

Runtime: 166 minutes

Rating: M

Language: English

TICKETS ⟶

“QUITE SIMPLY A MASTERPIECE, LEONE’S REVISIONIST WESTERN IS A MYTHIC SPECTACLE OF A FILM AND A LANDMARK IN CINEMA HISTORY” — FILM4

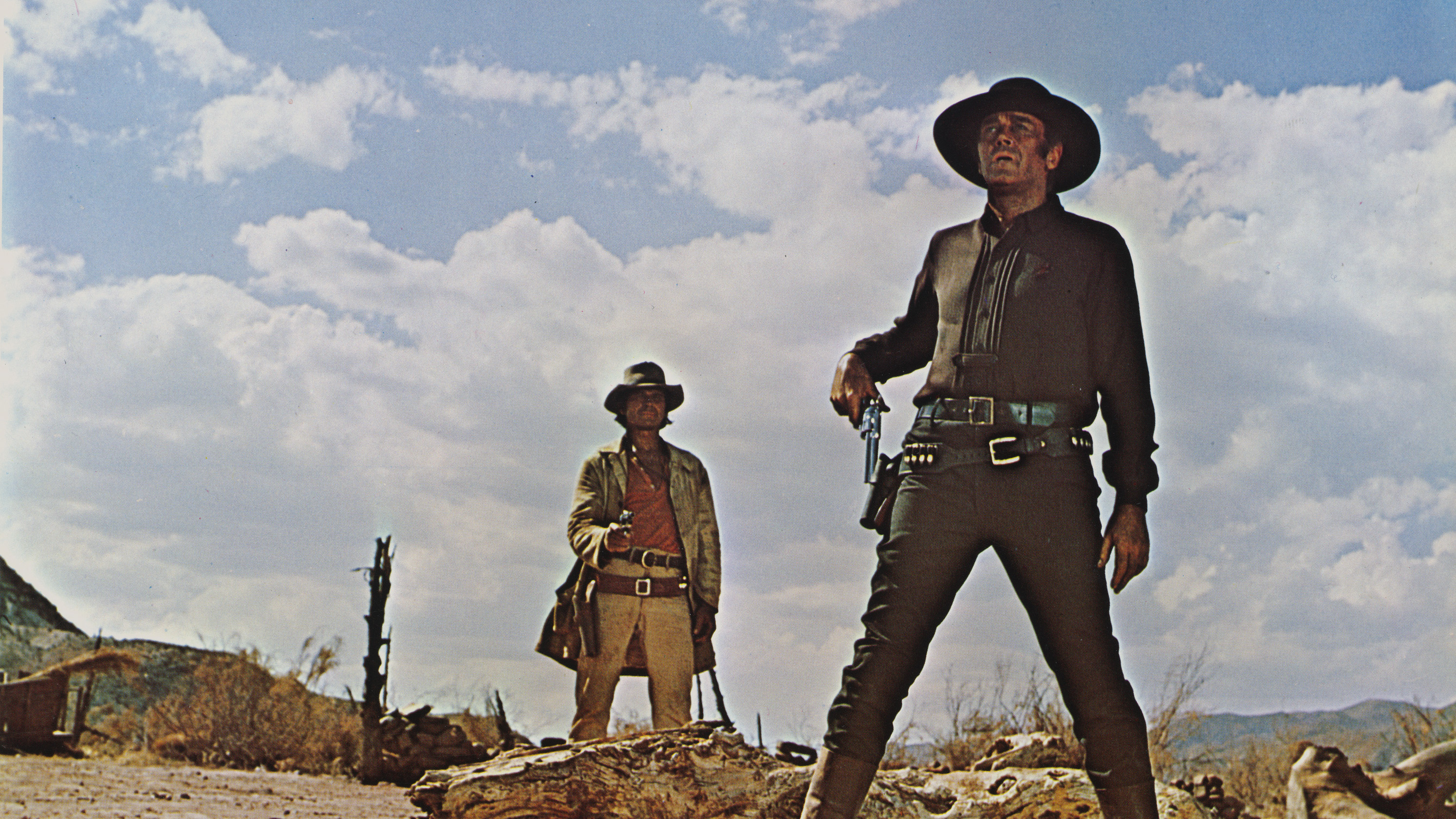

In hindsight, Sergio Leone’s earlier Westerns were mere warm-ups for this sprawling, operatic, epic about a mysterious stranger (Charles Bronson) and an ageing gunfighter (Jason Robards) joining forces to protect a widow (Claudia Cardinale) and her land from a gun-for-hire (Henry Fonda) and his gang of assassins who work for the railroad as it expands across the West.

It’s got everything – achingly beautiful music from the maestro Ennio Morricone; widescreen cinematography from Tonino Delli Colli; scriptwriters Bernardo Bertolucci, Dario Argento and Leone; perhaps the best pre-titles sequence ever made; Henry Fonda playing against type as a ruthless, vicious killer; and a story with all the frontier justice, frontier love, simmering revenge and lawless power you could wish for. A sumptuous, elegiac closing of an era.

The new 4K restoration includes scenes that were deleted for its first release.

“Long live Leone’s timeless monument to the death of the West itself…Critical tools needed are eyes and ears. This is Cinema.” — Paul Taylor, Time Out Film Guide

Introduced by Jane Mills, Film-maker, critic, Hon. Associate Professor, School of the Arts and Media, University of New South Wales.

Cinema Reborn is grateful for the support of the Instituto Italiano Di Cultura in the presentation of Once Upon a Time in the West.

FILM NOTES

By Adrian Danks

Sergio Leone:

Sergio Leone (1929-1969) was born into the cinema. The son of a prominent silent-era director and actress – Roberto Roberti (Vincenzo Leone) and Bice Valerian – Leone was destined to make movies. He entered the postwar Italian cinema in the late 1940s while still a teenager and, for over ten years, worked as an assistant or second unit director on at least 30 films. These included many undistinguished and generic movies – an equally important training ground for the budding director – as well as significant works of postwar Italian cinema and Hollywood offshore co-production. In one of his first assignments when still a teenager he worked as assistant director to Vittorio De Sica on Bicycle Thieves (1948), but he was also sought after on large-scale productions such as Quo Vadis (Mervyn LeRoy, 1951), Helen of Troy (Robert Wise, 1956), The Nun’s Story (Fred Zinnemann, 1959), Ben-Hur (William Wyler, 1959) and Sodom and Gomorrah (Robert Aldrich, 1962). This experience allowed Leone to learn from major directors of both neorealism and Hollywood genre cinema – particularly the western – and this emphasis on realistic detail and larger-than-life archetypes would go on to define his work as a filmmaker.

Although he contributed to several more productions as an assistant and second unit director, Leone’s breakthrough came on The Last of Days of Pompeii (1959). When the film’s director, Mario Bonnard, became ill, both he and fellow assistant Sergio Corbucci took over directorial duties. Leone had also started to contribute to screenplays within the vastly popular sword-and-sandal (peplum) cycle or genre, and it was inevitable that his first film as director would be within this familiar though increasingly exhausted form: The Colossus of Rhodes (1961). Although a relatively distinguished and stylish example of its type, going on to make a profit in Italy and the United States, it merely helped pave the way for Leone’s true calling as a commercial filmmaker who would bring together the traditions, forms and archetypes of American and Italian cinema through his baroque and often hyperbolic take on the western. His second film and first western, A Fistful of Dollars (1964), was initially released to an underwhelming critical response, but it would go on to become one of the most financially successful films ever released in Italy (it was also extremely popular in France and Germany). Although it was preceded by other, nascent examples of what came to be called the ‘spaghetti western’, Leone’s sophomore effort proved massively influential. Its emphasis upon and combination of gesture, the wide closeup, archetypes, black humour, aphoristic dialogue, violence, desolate landscapes and ramshackle buildings, Eisensteinian typologies, lived-in, macrocosmic faces, and Ennio Morricone’s dynamic, idiosyncratically distinctive, musique concrète-like soundscapes setting the tone and style for the spaghetti western boom of the next ten years. By the time of its wider international release by United Artists in early 1967 – after copyright issues around its borrowings from Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961) were “resolved” – it had already been joined by two ill-defined sequels, For a Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), in what came to be called the “Man with No Name” trilogy, each starring Clint Eastwood. It was with the release of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly that Leone became a truly prominent international filmmaker who could draw upon significant support for his outsized, highly Europeanised reimagination of Hollywood genre cinema.

After such a productive and successful start as a feature director, Leone would go on to complete only three further films over the next 20 years as the scope of his productions increased in scale and he moved between Europe and the United States. Both Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) and Once Upon a Time in America (1984) are often regarded as definitive, summary works of their particular genres, while Duck, You Sucker! (aka, A Fistful of Dynamite, 1971) remains Leone’s most underrated work, an extraordinarily playful and sometimes devastating take on the Mexican revolution. In the last 15 years of his career, Leone often thought big, worked as a producer and occasional “assistant” or “fixer” on productions that needed his particular genius, made advertisements, and tried to summon large-scale films out of an increasingly straitened and hard-headed filmmaking environment. His last film, the truly large-budget Once Upon a Time in America, was a project he had been trying to get up since the mid-1960s. Its mixed critical response – a fair amount of which focused on Leone’s questionable gender politics, an overall limitation of his work – and significant financial failure – the first of Leone’s career – making future productions of that scale increasingly difficult. Leone, of course, forged on, reportedly securing almost half of the vast $100 million budget for the planned Leningrad: The 900 Days before dying of a heart attack in late April 1989. Despite his small but still outsized filmography, Leone, a man of immense vision and voracious appetites, remains one of the great and most influential revisionists of international genre cinema, as well as one of its truly distinctive stylists.

Although he contributed to several more productions as an assistant and second unit director, Leone’s breakthrough came on The Last of Days of Pompeii (1959). When the film’s director, Mario Bonnard, became ill, both he and fellow assistant Sergio Corbucci took over directorial duties. Leone had also started to contribute to screenplays within the vastly popular sword-and-sandal (peplum) cycle or genre, and it was inevitable that his first film as director would be within this familiar though increasingly exhausted form: The Colossus of Rhodes (1961). Although a relatively distinguished and stylish example of its type, going on to make a profit in Italy and the United States, it merely helped pave the way for Leone’s true calling as a commercial filmmaker who would bring together the traditions, forms and archetypes of American and Italian cinema through his baroque and often hyperbolic take on the western. His second film and first western, A Fistful of Dollars (1964), was initially released to an underwhelming critical response, but it would go on to become one of the most financially successful films ever released in Italy (it was also extremely popular in France and Germany). Although it was preceded by other, nascent examples of what came to be called the ‘spaghetti western’, Leone’s sophomore effort proved massively influential. Its emphasis upon and combination of gesture, the wide closeup, archetypes, black humour, aphoristic dialogue, violence, desolate landscapes and ramshackle buildings, Eisensteinian typologies, lived-in, macrocosmic faces, and Ennio Morricone’s dynamic, idiosyncratically distinctive, musique concrète-like soundscapes setting the tone and style for the spaghetti western boom of the next ten years. By the time of its wider international release by United Artists in early 1967 – after copyright issues around its borrowings from Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961) were “resolved” – it had already been joined by two ill-defined sequels, For a Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), in what came to be called the “Man with No Name” trilogy, each starring Clint Eastwood. It was with the release of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly that Leone became a truly prominent international filmmaker who could draw upon significant support for his outsized, highly Europeanised reimagination of Hollywood genre cinema.

After such a productive and successful start as a feature director, Leone would go on to complete only three further films over the next 20 years as the scope of his productions increased in scale and he moved between Europe and the United States. Both Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) and Once Upon a Time in America (1984) are often regarded as definitive, summary works of their particular genres, while Duck, You Sucker! (aka, A Fistful of Dynamite, 1971) remains Leone’s most underrated work, an extraordinarily playful and sometimes devastating take on the Mexican revolution. In the last 15 years of his career, Leone often thought big, worked as a producer and occasional “assistant” or “fixer” on productions that needed his particular genius, made advertisements, and tried to summon large-scale films out of an increasingly straitened and hard-headed filmmaking environment. His last film, the truly large-budget Once Upon a Time in America, was a project he had been trying to get up since the mid-1960s. Its mixed critical response – a fair amount of which focused on Leone’s questionable gender politics, an overall limitation of his work – and significant financial failure – the first of Leone’s career – making future productions of that scale increasingly difficult. Leone, of course, forged on, reportedly securing almost half of the vast $100 million budget for the planned Leningrad: The 900 Days before dying of a heart attack in late April 1989. Despite his small but still outsized filmography, Leone, a man of immense vision and voracious appetites, remains one of the great and most influential revisionists of international genre cinema, as well as one of its truly distinctive stylists.

The Film:

Once Upon a Time in the West is now widely regarded as Leone’s masterpiece and a crucial gateway between the American and European western. Although deeply indebted to the history of the genre – it includes multiple direct references to such celebrated, auteur-driven westerns as The Searchers (John Ford, 1956), Run of the Arrow (Samuel Fuller, 1957), Western Union (Fritz Lang, 1941), High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1952), Man of the West (Anthony Mann, 1958), The Iron Horse (John Ford, 1924), Johnny Guitar (Nicholas Ray, 1954) – most extensively – and many others, it is as much an inventor or re-shaper of forms as it is a work of dutiful homage. Both Jean Baudrillard and Umberto Eco celebrated its postmodern assemblage of archetypes, conventions and intertextuality, seeing its overwhelming summation or pastiche of the genre as its great contribution. This common view of Leone’s film sees it as an overwhelming “hall of mirrors” whose only point of reference is other westerns. Filmmaker John Boorman, meanwhile, saw Leone’s film as a kind of endpoint, “making the texture and detail [of the genre] real, but ruthlessly shearing away the recent accretions of the ‘real’ West and its psychological motivations”. Boorman placed the film within the context of the genre’s wider fate in the late 1960s as an often exhausted and trail-sore form that was struggling to survive its endless television, international and revisionist variations: “In Once Upon a Time in the West, the Western reaches its apotheosis. Leone’s title is a declaration of intent and also his gift to America of its lost fairy stories. This is the kind of masterpiece that can occur outside trends and fashion. It is both the greatest and the last Western”. Although it is most definitely not the “last Western” – Sam Peckinpah would pick up many of the leads opened up by Leone – Once Upon a Time in the West certainly has a sense of the end of things. It stages an epic battle between core archetypes of the old West – as well as actors well associated with their previous roles across the genre – in a manner that is both epic, or god-like and that emphasises that the world around them has moved on. For example, the final showdown between Fonda’s Frank and Bronson’s Harmonica is staged to the side of a large homestead and suffers the complete indifference of the multitude of busy workers who are building a railway through the property.

Many commentators have claimed that Leone’s film continues the cynical, highly revisionist and deeply critical preoccupations of his earlier trilogy and of the broader spaghetti cycle, but it is equally a direct homage and celebration of the key works and themes of the wider genre. It also draws deeply on such revisionist Hollywood westerns as John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), Robert Aldrich’s Vera Cruz (1954; where Bronson first plays a harmonica!), and Howards Hawks’ Rio Bravo (1959). Its central place in the history of the western is based on this movement between critique and homage, comedy and drama, its drawing together of footage shot in the Almería region of Spain (predominantly in the Tabernas Desert), Cinecittà in Rome and Ford’s beloved Monument Valley on the Utah-Arizona border. It is obviously a film preoccupied with the history and the politics of the West – elements highlighted in the extended treatment initially completed by Leone and the more radical cineastes Dario Argento and Bernardo Bertolucci – but its true heart lies in how this history intertwines with its popular narrativisation in the cinema. Once Upon a Time in the West references well-worn narrative tropes, character types, and even roles played by the actors it uses – this ranges across dominant perceptions of Fonda’s upstanding star persona and how it is used and upended, as well as Cardinale’s earlier role in Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard (1963) – but Leone’s film remains utterly unique.

As mentioned earlier, the massive international success of the “Dollars trilogy” granted Leone significant access to international finance and stars. Paramount allowed Leone significant largesse in his choice of subject, and helped provide a budget that was three or four times higher than his previous film. Although Leone would go on to be remembered as a profligate filmmaker during the making of Once Upon a Time in America, his other films are remarkable for the scale and detail they achieve on relatively modest budgets. A significant proportion of the budget on Once Upon a Time in America was taken up by the hiring a prominent actors and stars like Fonda, Jason Robards, Cardinale and Bronson, but the epic economy of Leone’s approach can be seen in the careful movement between footage shot in the various locations as well as the way that Morricone’s extraordinary score is used to connect and bridge together the sometimes disparate set-piece sequences. Once Upon a Time in the West is commonly considered a financial failure due to its lack of audience support in the United States – where it only returned about $1,000,000 – and the relative decline in attendances in Italy in comparison to the three previous Leone films. In actuality, it appears to have been a much more divisive work – the critical response was generally negative in Italy, but the film was celebrated by figures such as Andrew Sarris and Graham Greene – that did amass significant support in particular countries. For example, it still stands as one of the top ten films of all-time at the box office in Germany and France, where its returns dwarfed that of Leone’s previous westerns. The mixed critical response to Once Upon a Time in the West also marks the point at which Leone fully emerges as an auteur completely self-aware of his own style and how it is perceived.

Once Upon a Time in the West presents a relatively coherent narrative that is driven by themes of revenge, the march of progress, the indifference of capitalism and the playing out of archetypes who no longer have a place in a changing world. As Robards’ fatally wounded Cheyenne proclaims towards the end of the film, it also “has something to do with death” (Robards is wonderful but gives little sense of his character’s supposed Mexican heritage it should be noted). There is nothing particularly startling or novel about the film’s focus on the end of the “old West”, a theme that dates back to the very early renditions of the western genre formed in the years before Frederick Jackson Turner would proclaim the “closing of the frontier” – during a paper delivered at 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The greatness of Leone’s film lies in its sense of scale. Not just of the extraordinary towns and sets built for the production and overseen by Carlo Simi – just look at the uneven surface, grain and expanse of the wood in the justly famous opening shoot-out sequence – but the geography of the bodies and faces it puts on display (Simi’s choice of costumes are also extraordinary). It is almost impossible – now – to see a widescreen closeup of a pair of eyes and not think of Leone. But it is the combination of minimalism and maximalism that best signifies the extraordinary contribution of both Leone and Morricone. The vast but simple opening sequence combines these qualities in their most refined iteration. Morricone, at one point, claimed that his greatest “score” was the combination of the isolated, concrete sounds of squeaking windmills, train whistles, harmonicas and buzzing flies – amongst many others – that provides the rhythm to this sequence. The combination of tension, space, brief, decisive action and elongated, epic time also prepares us for the “otherworldly” film that will follow. Leone played recordings of the score on set to help establish a particular mood and rhythm and grant a sense of operatic drama to the performances and amplified actions. Most commentators only discuss Once Upon a Time in the West and Leone’s other westerns in relation to their dominant genre, but they are also beholden to the ensemble forms of opera, commedia dell’arte, epic theatre and neorealism. In the end – and this is a film all about endings and one new beginning (Cardinale’s earth mother Jill carrying water to the railroad workers in the final moments) – this fusion of the modern and the ancient, the United States and Europe, the western and other forms, helped to redefine the genre. The mythic, almost fairy tale-like Once Upon a Time in the West is a truly landmark work that divides the genre.

Notes:

Many commentators have claimed that Leone’s film continues the cynical, highly revisionist and deeply critical preoccupations of his earlier trilogy and of the broader spaghetti cycle, but it is equally a direct homage and celebration of the key works and themes of the wider genre. It also draws deeply on such revisionist Hollywood westerns as John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), Robert Aldrich’s Vera Cruz (1954; where Bronson first plays a harmonica!), and Howards Hawks’ Rio Bravo (1959). Its central place in the history of the western is based on this movement between critique and homage, comedy and drama, its drawing together of footage shot in the Almería region of Spain (predominantly in the Tabernas Desert), Cinecittà in Rome and Ford’s beloved Monument Valley on the Utah-Arizona border. It is obviously a film preoccupied with the history and the politics of the West – elements highlighted in the extended treatment initially completed by Leone and the more radical cineastes Dario Argento and Bernardo Bertolucci – but its true heart lies in how this history intertwines with its popular narrativisation in the cinema. Once Upon a Time in the West references well-worn narrative tropes, character types, and even roles played by the actors it uses – this ranges across dominant perceptions of Fonda’s upstanding star persona and how it is used and upended, as well as Cardinale’s earlier role in Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard (1963) – but Leone’s film remains utterly unique.

As mentioned earlier, the massive international success of the “Dollars trilogy” granted Leone significant access to international finance and stars. Paramount allowed Leone significant largesse in his choice of subject, and helped provide a budget that was three or four times higher than his previous film. Although Leone would go on to be remembered as a profligate filmmaker during the making of Once Upon a Time in America, his other films are remarkable for the scale and detail they achieve on relatively modest budgets. A significant proportion of the budget on Once Upon a Time in America was taken up by the hiring a prominent actors and stars like Fonda, Jason Robards, Cardinale and Bronson, but the epic economy of Leone’s approach can be seen in the careful movement between footage shot in the various locations as well as the way that Morricone’s extraordinary score is used to connect and bridge together the sometimes disparate set-piece sequences. Once Upon a Time in the West is commonly considered a financial failure due to its lack of audience support in the United States – where it only returned about $1,000,000 – and the relative decline in attendances in Italy in comparison to the three previous Leone films. In actuality, it appears to have been a much more divisive work – the critical response was generally negative in Italy, but the film was celebrated by figures such as Andrew Sarris and Graham Greene – that did amass significant support in particular countries. For example, it still stands as one of the top ten films of all-time at the box office in Germany and France, where its returns dwarfed that of Leone’s previous westerns. The mixed critical response to Once Upon a Time in the West also marks the point at which Leone fully emerges as an auteur completely self-aware of his own style and how it is perceived.

Once Upon a Time in the West presents a relatively coherent narrative that is driven by themes of revenge, the march of progress, the indifference of capitalism and the playing out of archetypes who no longer have a place in a changing world. As Robards’ fatally wounded Cheyenne proclaims towards the end of the film, it also “has something to do with death” (Robards is wonderful but gives little sense of his character’s supposed Mexican heritage it should be noted). There is nothing particularly startling or novel about the film’s focus on the end of the “old West”, a theme that dates back to the very early renditions of the western genre formed in the years before Frederick Jackson Turner would proclaim the “closing of the frontier” – during a paper delivered at 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The greatness of Leone’s film lies in its sense of scale. Not just of the extraordinary towns and sets built for the production and overseen by Carlo Simi – just look at the uneven surface, grain and expanse of the wood in the justly famous opening shoot-out sequence – but the geography of the bodies and faces it puts on display (Simi’s choice of costumes are also extraordinary). It is almost impossible – now – to see a widescreen closeup of a pair of eyes and not think of Leone. But it is the combination of minimalism and maximalism that best signifies the extraordinary contribution of both Leone and Morricone. The vast but simple opening sequence combines these qualities in their most refined iteration. Morricone, at one point, claimed that his greatest “score” was the combination of the isolated, concrete sounds of squeaking windmills, train whistles, harmonicas and buzzing flies – amongst many others – that provides the rhythm to this sequence. The combination of tension, space, brief, decisive action and elongated, epic time also prepares us for the “otherworldly” film that will follow. Leone played recordings of the score on set to help establish a particular mood and rhythm and grant a sense of operatic drama to the performances and amplified actions. Most commentators only discuss Once Upon a Time in the West and Leone’s other westerns in relation to their dominant genre, but they are also beholden to the ensemble forms of opera, commedia dell’arte, epic theatre and neorealism. In the end – and this is a film all about endings and one new beginning (Cardinale’s earth mother Jill carrying water to the railroad workers in the final moments) – this fusion of the modern and the ancient, the United States and Europe, the western and other forms, helped to redefine the genre. The mythic, almost fairy tale-like Once Upon a Time in the West is a truly landmark work that divides the genre.

Notes:

- Boorman quoted in Christopher Frayling, Sergio Leone: Something to Do with Death (London and New York: Faber and Faber, 2000): 299.

The Restoration:

Screening will be the 166 min. ‘International’ cut of the

film, 10 mins shorter than the Italian ‘Director’s Cut’, but 20 minutes longer

than the original 1968 release in the US and Australia. 4K scan by L'Immagine Ritrovata, Bologna. Original

restoration made possible with support by The Film Foundation and The Rome Film

Festival, in association with Sergio Leone Productions and Paramount Pictures.

Credits:

C'era una volta il West aka Once Upon a Time in the West | Dir: Sergio LEONE | Italy, USA | 1968 | 166 mins | 4K DCP (orig. 35mm) | Colour | 2.35:1 | Mono Sound | English Version | (M)

Production Companies: Rafran Cinematografica, San Marco, Paramount Pictures | Producer: Fulvio MORSELLA | Script: Dario ARGENTO & Bernardo BERTOLUCCI, Sergio DONATI & Sergio LEONE | Photography: Tonino DELLI COLLI | Editor: Nino BARAGLI | Art Direction: Carlo SIMI| Sound: Fausto ANCILLAI, Luciano ANZILOTTI, Italo CAMERACANNA, Claudio MAILELLI, Elio PACELLA, | Music: Ennio MORRICONE | Costumes: Carlo SIMI.

Cast: Claudia CARDINALE (‘Jill McBain’), Henry FONDA (‘Frank’), Jason ROBARDS (‘Cheyenne Gutiérrez’),Charles BRONSON (‘Harmonica”), Gabriele FERZETTI (‘Morton’), Paolo STOPPA (‘Sam’), Frank WOLFF (‘Brett McBain’), Woody STRODE (‘Stony’), Jack ELAM (‘Snaky’), Keenan WYNN (‘Sherriff’), Lionel STANDER (‘Cantina Barman’).

Source: Park Circus.

Credits:

C'era una volta il West aka Once Upon a Time in the West | Dir: Sergio LEONE | Italy, USA | 1968 | 166 mins | 4K DCP (orig. 35mm) | Colour | 2.35:1 | Mono Sound | English Version | (M)

Production Companies: Rafran Cinematografica, San Marco, Paramount Pictures | Producer: Fulvio MORSELLA | Script: Dario ARGENTO & Bernardo BERTOLUCCI, Sergio DONATI & Sergio LEONE | Photography: Tonino DELLI COLLI | Editor: Nino BARAGLI | Art Direction: Carlo SIMI| Sound: Fausto ANCILLAI, Luciano ANZILOTTI, Italo CAMERACANNA, Claudio MAILELLI, Elio PACELLA, | Music: Ennio MORRICONE | Costumes: Carlo SIMI.

Cast: Claudia CARDINALE (‘Jill McBain’), Henry FONDA (‘Frank’), Jason ROBARDS (‘Cheyenne Gutiérrez’),Charles BRONSON (‘Harmonica”), Gabriele FERZETTI (‘Morton’), Paolo STOPPA (‘Sam’), Frank WOLFF (‘Brett McBain’), Woody STRODE (‘Stony’), Jack ELAM (‘Snaky’), Keenan WYNN (‘Sherriff’), Lionel STANDER (‘Cantina Barman’).

Source: Park Circus.