LA PISCINE (1969)

6:00 PM, Friday April 28

Australian Premiere: Introduced by John Duigan

10:00 AM, Sunday April 30

Randwick Ritz

Director: Jacques Deray

Country: France

Year: 1969

Runtime: 122 minutes

Rating: U15+

Language: French, English subtitles

TICKETS ⟶

Australian Premiere: Introduced by John Duigan

10:00 AM, Sunday April 30

Randwick Ritz

Director: Jacques Deray

Country: France

Year: 1969

Runtime: 122 minutes

Rating: U15+

Language: French, English subtitles

TICKETS ⟶

LA PISCINE/ THE SWIMMING POOL

AUSTRALIAN PREMIERE OF THE 4K RESTORATION

"A tour de force of sexual longing and controlled suspense." — Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian

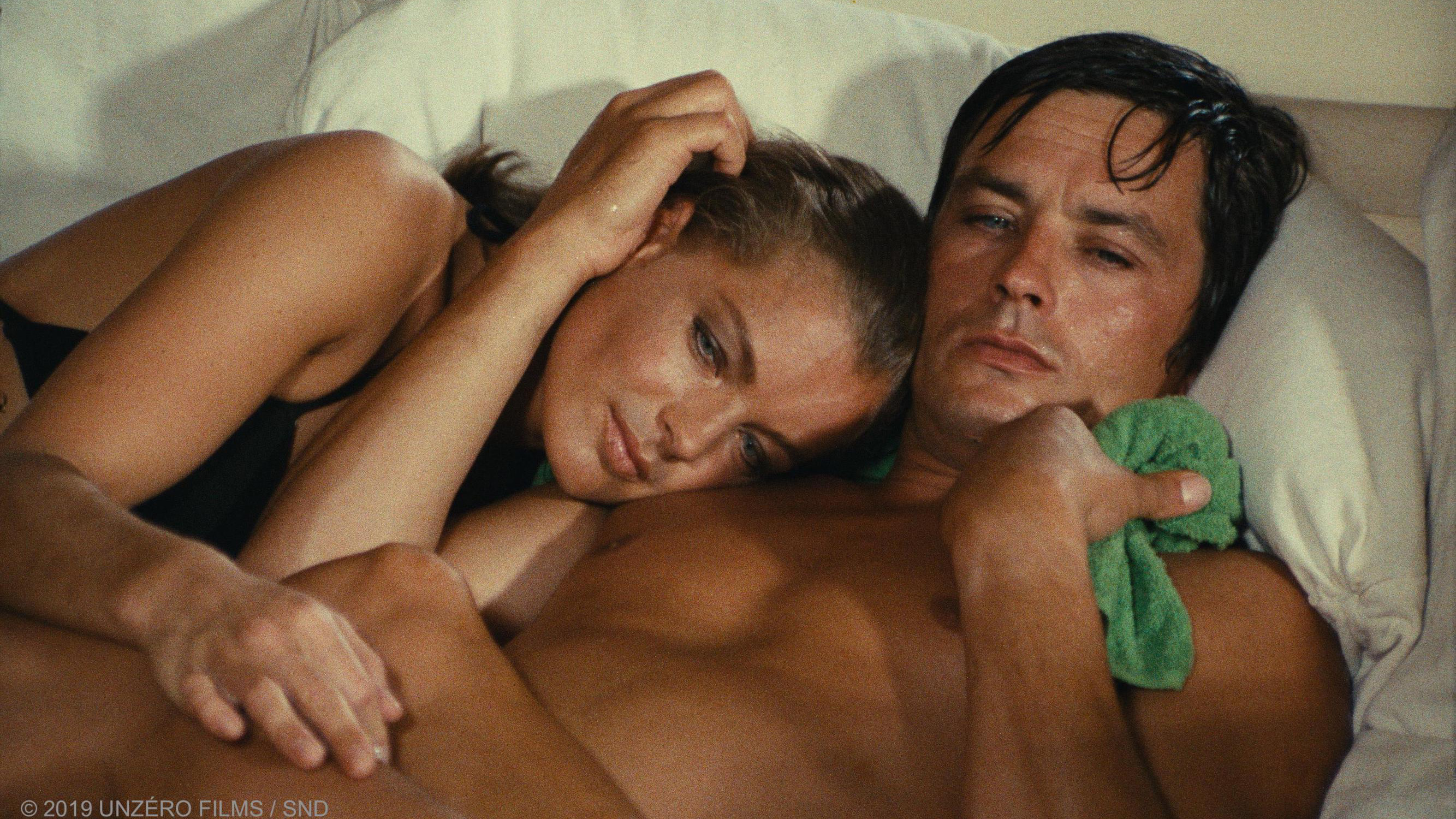

A sensual, sexy, psychological drama that takes a surprising turn into a police procedural. Lovers Jean-Paul (Alain Delon) and Marianne (Romy Schneider) are on an apparently happy holiday in a villa in the south of France when Marianne’s ex-lover Harry (Maurice Ronet) turns up hoping to rekindle his old romance. Jean-Paul starts taking more than a passing interest in Harry’s teenage daughter (Jane Birkin). Stunning 4K restoration with cinematography from Jean-Jacques Tarbès and music by Michel Legrand.

“The boiling point for simmering jealousy, male-female possessiveness and the hint of violence…” — Michael Calleri

“Witnessing toxic masculinity taken to its logical extreme has never been this satisfying.” — Ruben Rosario

The 6pm session on Friday 28 April will be introduced by John Duigan, a writer/director and obscure novelist.

AUSTRALIAN PREMIERE OF THE 4K RESTORATION

"A tour de force of sexual longing and controlled suspense." — Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian

A sensual, sexy, psychological drama that takes a surprising turn into a police procedural. Lovers Jean-Paul (Alain Delon) and Marianne (Romy Schneider) are on an apparently happy holiday in a villa in the south of France when Marianne’s ex-lover Harry (Maurice Ronet) turns up hoping to rekindle his old romance. Jean-Paul starts taking more than a passing interest in Harry’s teenage daughter (Jane Birkin). Stunning 4K restoration with cinematography from Jean-Jacques Tarbès and music by Michel Legrand.

“The boiling point for simmering jealousy, male-female possessiveness and the hint of violence…” — Michael Calleri

“Witnessing toxic masculinity taken to its logical extreme has never been this satisfying.” — Ruben Rosario

The 6pm session on Friday 28 April will be introduced by John Duigan, a writer/director and obscure novelist.

FILM NOTES

By Scott Murray

Jacques Deray

Born Jacques Desrayaud in Lyon in 1929, Jacques Deray became one of France’s most successful directors, particularly of films noir and crime stories (including 1970’s international box-office smash Borsalino). He was also one of its most underrated filmmakers. Box-office success can be poison for one’s critical reputation in France. Just ask Claude Lelouch.

Deray worked with the biggest French stars, including Alain Delon (9 films) and Jean-Paul Belmondo (4). He was brilliant at capturing tension between Alpha males, no matter whether they were played by Delon and Jean-Louis Trintignant; Delon and Belmondo; or Delon and Maurice Ronet.

If Deray had a flaw as a director, he was sometimes too trendily stylish in his décors and costumes, which could date quickly. But he was a master stylist who has often been compared to Jean-Pierre Melville. Deray tends to suffer in the comparison, but Melville’s genius was always on display, sometimes a little showily, whereas Deray hid his prodigious skill and intelligence behind a workmanlike façade.

For many Deray fans, La Piscine (1969) is the masterpiece, but other of his movies to seek out include 1963’s Rififi in Tokyo (an homage to Jules Dassin’s Rififi), that same year’s Symphonie pour Un Massacre (a drug deal goes very wrong), 1971’s Un Peu de Soleil dans l’Eau Froide (based on the Françoise Sagan novel about a threesome) and 1975’s Flic Story (the nine-year pursuit of a serial killer played chillingly by Trintignant). However, all of Deray’s œuvre deserves scrutiny and celebration.

The Film

When writer-director Jacques Deray was preparing La Piscine, which is based on “scenario original” by Jean-Emmanuel Conil (a pseudonym of British writer Alain Page,) the intention of Deray and his co-writer Jean-Claude Carrière was that the ending be changed. La Piscine may seem a deceptively simple story about desire and conflict amongst a foursome, but the film’s amorality unsettled more than a few, and particularly Franco’s Spanish government, which demanded for local release a closing shot be added of the police arriving to arrest the villain.

The setting is a villa (Domaine de l’Oumède) in Ramatuelle, the idyllic Provençal village to which British photographer David Hamilton had already moved to live and take photographs of young women for books that sold millions in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and also make highly commercial films such as Bilitis(scripted by Catherine Breillat, no less). Hamilton’s celebration of “innocence” precisely captured the zeitgeist (though it has been the subject of much negative re-evaluation since).

La Piscine equally set out to capture the times, but does so across a wider age spectrum, its hermetic world the antithesis of innocent.

The film begins with Michel Legrand’s bouncy title song (booming out with what seems deliberate incongruity) as the camera glides above a pristine swimming pool to Jean-Paul (Alain Delon), who is lying in blissful self-adoration on the pool’s edge. He turns his head towards camera but we can’t see his eyes because of the dark-lensed sunglasses. He has been called from offscreen by Marianne (Romy Schneider) and Jean-Paul is no doubt looking at her, but it feels like he is looking at us, and it is uncomfortable.

This is a Delon characterisation that is as alarming as it is sexually exciting, with a disdain and threat in almost everything he does. But has any male star looked so beautiful, his skin so perfectly bronzed, his physique and movement as lithe as a tiger’s?

“Approach at own risk” would be an appropriate warning, and we fear for Marianne as she joins him poolside for one of the most unsettling physical encounters in cinema. Against our better judgement, we are attracted by the animal-like intensity of their desire, but recoil from what feels like its exhibitionism, even though there is no one there except us, the complicit viewers.

Marianne lies on top of Jean-Paul in a black bikini (the top of which he will soon tear away) and she asks him to scratch her back. He does so in a claw-like manner, as if he could rip away her skin at any moment, should he wish (prefiguring Walerian Borowczyk’s gender-reversedCérémonie d’Amour, 1987).

The edginess is intensified when what should be a playful tossing of a beloved into a pool is filled with menace.

Into this sexual cauldron come Harry (Maurice Ronet) and his 18-year-old daughter, Pénélope (Jane Birkin). There is a vibrant bonhomie between old mates Harry and Jean-Paul, but also a sense that this could just be playacting. The audience unconsciously shifts into armchair detective mode, wondering which of the foursome will pair off with whom, and whether that relationship will be loving or dangerous or both.

Even young Pénélope, with her awkward innocence, may be a viper in their midst.

After Marianne invites Harry and Pénélope to stay (which Harry’s reaction makes feel both intended and sinister), Jean-Paul ushers them towards a villa entrance. Surprisingly, Jean-Paul does not wait for Pénélope to go in ahead of him (the custom of the day), but then suddenly stops to let Pénélope pass. Has he noticed his ungentlemanly act? But, if so, why did he leave so little space for her to move through?

This tiny moment, ambiguous and unsettling, is brilliantly staged, with no over-stressed change of camera position or lens. Deray’s restraint is always a virtue.

If ever a film were about its casting and the handsomeness and offscreen lives of its actors, this is it. It is not aroman à clef, but it does play off the audience’s knowledge of – and often insatiable interest in – the private lives of stars.

The press was obsessed with Delon and Schneider, who became a couple while starring in an Italian stage version of John Ford’s ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore, directed by Luchino Visconti in Paris in 1961. They broke up in December 1963, but remained close friends.

Schneider was already world-famous for playing as a teenager Empress Elisabeth of Austria in three Sissi films (1955-7), a role she reprised decades later in Visconti’sLudwig (1973). Schneider also famously had an unrequited love for Visconti, who had an unrequited love for Delon, a seemingly ice-cool Casanova whose every affair hit the front pages and who cast his amours du jour (often explicitly) in films he produced and/or directed.

Apart from Burton and Taylor (who had no need of Christian names back then), it would be hard to imagine a more super-charged Sixties cinematic coupling than Schneider and Delon, or a more stellar accompanying cast than Maurice Ronet and Jane Birkin.

Ronet, who was discovered by Jacques Becker at age 22 (for 1949’s Rendez-vous de Juillet, which Becker wrote for him), was a darkly brooding and hypnotic presence in many wonderful films, including several by Claude Chabrol and François Truffaut.

As for Birkin, she was a hip 18-year old British model who was discovered by film audiences in Richard Lester’s The Knack … and how to get it (1965), and whose often-censored nude scene with Gillian Hills in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup (1970), private and working relationship with singer-composer Serge Gainsbourg, a naked lesbian moment with Brigitte Bardot in Roger Vadim’s Don Juan ou Don Juan Était Une Femme … (1973) and countless other contributions to the counter culture kept the presses spinning, and saw Hermès’ create “The Birkin” bag, still one of the world’s most sought-after luxury artefacts.

These were not shy, quiet-living, self-denying thespians, but screen icons known internationally for their sex appeal and scandals, and whose lives and careers interlaced in many pop-culture ways.

Deray knows all this and uses it well in La Piscine, which is obsessed with objectification, iconography and physical beauty: of the landscape, the eerie tree by the pool, the Edenic view down the Ramatuelle hill to the Mediterranean, the beguiling villa and the pretty humans staying there, the camera forever honing in on their perfect skin, just as a mosquito might as it gets ready to feast on unsuspecting blood, and leave, perhaps, a poison that will eat away at its host until death.

La Piscineis a searingly beautiful film, shot in a Provençal paradise with actors already immortalised on bedroom posters across the globe, but at its narrative heart it is virulent and deadly.

The Restoration

The

film was first restored in 2007 using the original negative. The technology of

the day had its limits and compromises had to be made. In order to capture

details in the strong light without losingbin the middle and dark ranges, the

compromises had their effect in the details on the paving round the pool and

the sheens of the skin. Still it was a substantial improvement in returning the

film to its original 35mm look.

Twelve years later for the film’s fiftieth anniversary the opportunity was taken to re-examine the inevitable compromises of the earlier restoration work and go much further towards rec-creating a copy as near as possible to the original for a 4K restoration. This involved extensive work on the image, the sound recording, Michel Legrand’s music and the original titles which were entirely re-shot

Twelve years later for the film’s fiftieth anniversary the opportunity was taken to re-examine the inevitable compromises of the earlier restoration work and go much further towards rec-creating a copy as near as possible to the original for a 4K restoration. This involved extensive work on the image, the sound recording, Michel Legrand’s music and the original titles which were entirely re-shot

Credits

Director: Jacques DERAY | France, Italy | 1969 | 122

mins. | 4K Flat DCP (orig. 35mm, 1.66:1) | Colour | Mono Sd. | French with Eng.

Subtitles | U/C15+.

Production Companies: Société Nouvelle de Cinématographie (SNC), Tritone Cinematografica | Producer: Gérard BEYTOUT | Script: Jean-Claude CARRIÈRE, Jacques DERAY, Jean-Emmanuel CONIL | Photography: Jean-Jacques TARBÈS | Editor: Paul CAYATTE | Production Design: Paul LAFFARGUE | Music: Michel LEGRAND | Costumes: André COURRÈGES.

Cast: Alain DELON (‘Jean-Paul’), Romy SCHEINDER (‘Marianne’), Maurice RONET (‘Harry’), Jane BIRKIN (‘Penelope’), Paul CRAUCHET (‘L'inspecteur Lévêque’).

Production Companies: Société Nouvelle de Cinématographie (SNC), Tritone Cinematografica | Producer: Gérard BEYTOUT | Script: Jean-Claude CARRIÈRE, Jacques DERAY, Jean-Emmanuel CONIL | Photography: Jean-Jacques TARBÈS | Editor: Paul CAYATTE | Production Design: Paul LAFFARGUE | Music: Michel LEGRAND | Costumes: André COURRÈGES.

Cast: Alain DELON (‘Jean-Paul’), Romy SCHEINDER (‘Marianne’), Maurice RONET (‘Harry’), Jane BIRKIN (‘Penelope’), Paul CRAUCHET (‘L'inspecteur Lévêque’).

|

|

|