BREAD AND DRIPPING (1982) +

HOW THE WEST WAS LOST (1987)

Randwick Ritz, Sydney:

6:00 PM

Tuesday May 06

Lido Cinemas, Melbourne:

5:30 PM

Friday May 09

Rating: G

Duration: 72 minutes

Country: Australia

Language: Njangamarda, Wanmun, Injibandi and English with English subtitles

Director: David Noakes

SYDNEY TICKETS ⟶

MELBOURNE TICKETS ⟶

6:00 PM

Tuesday May 06

Lido Cinemas, Melbourne:

5:30 PM

Friday May 09

Rating: G

Duration: 72 minutes

Country: Australia

Language: Njangamarda, Wanmun, Injibandi and English with English subtitles

Director: David Noakes

SYDNEY TICKETS ⟶

MELBOURNE TICKETS ⟶

HOW THE WEST WAS LOST

"[It] will always be the best, most honest and most entertaining record of the 1946 Strike ... It is an exhilarating, inspirational documentary that shows what people can achieve when they have vision, courage and solidarity." – Jerry Roberts, Pearls and Irritations

On 1 May 1946, 800 Aboriginal station workers walked off sheep stations in the north-west of Western Australia, marking the beginning of a carefully organised strike that was to last for at least three years, but never officially ended.

The strike was more than a demand for better wages and conditions. It was, in the words of Keith Connolly in the Melbourne Herald, 'a well-considered statement by a grievously exploited people, standing up for their rights and dignity'.

How The West Was Lost tells the story of a shameful yet still largely unknown piece of Australia’s tangled history.

Screens with...

BREAD AND DRIPPING

A film by Vic Smith, Margot Nash, Elizabeth Schaffer, Wendy Brady and Donna Foster. Country: Australia, Rating: G, Run Time: 17 minutes, Language: English

Four women recount their lives during the bleak years of the Depression of the 1930s. Tibby Whalan, Eileen Pittman, Beryl Armstrong and Mary Wright describe their struggles to survive and maintain families when faced with widespread unemployment, evictions and hardship.

How The West Was Lost introduced by David Noakes and Rose Murray at Ritz Cinemas and Lido Cinemas. Bread and Dripping introduced by Vic Smith and Elizabeth Schaffer at Ritz Cinemas.

A discussion with David Noakes and Rose Murray will be held after the screening in the upstairs mezzanine at the Ritz in Sydney and in the discussion space off the foyer at the Lido in Melbourne.

This screening is dedicated to Heather Williams, producer, and to the great courage and determination of the Pilbara striker families.

![]()

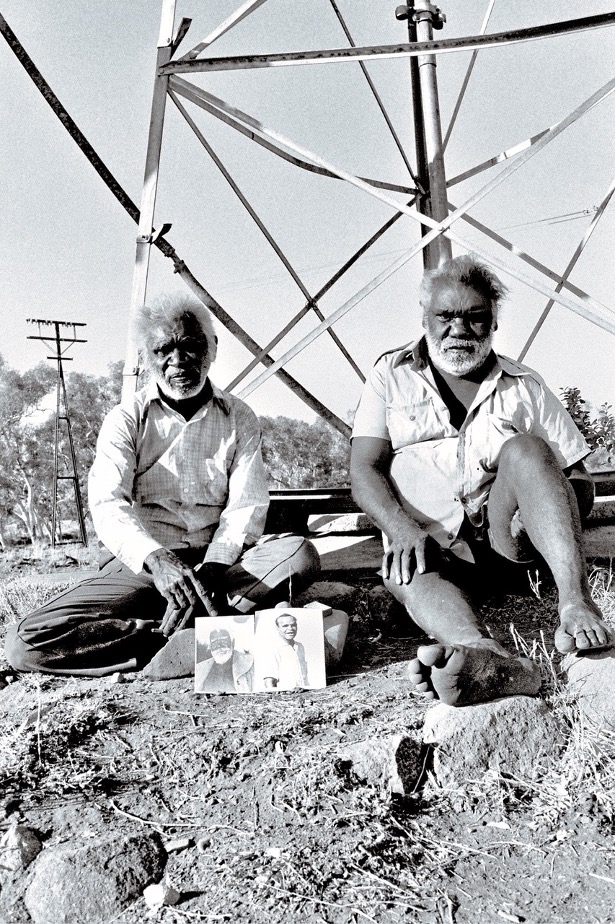

‘In 1942, the old ones gathered at Skull Springs. By there they discussed life under the white man. They selected Clancy and Dooley to spread the word of the strike.’ – Jacob Oberdoo –Striker (and Associate Producer)

‘This is Dooley Bin Bin and this is Clancy McKenna. These two men made a strike to help us out from under the white man. Like white man has Captain Cook – white fella, we have these two men, strong men, they helped us out from under the white man for better living.’ – Billy Thomas – Striker.

‘The story of how we treated the Blackfellas is really the story of a criminal act. And although we made all sorts of arrangements and promises we never intended to keep any of them, nor did we.’ – Don McLeod – white supporter and co-organiser of the strike.

"[It] will always be the best, most honest and most entertaining record of the 1946 Strike ... It is an exhilarating, inspirational documentary that shows what people can achieve when they have vision, courage and solidarity." – Jerry Roberts, Pearls and Irritations

On 1 May 1946, 800 Aboriginal station workers walked off sheep stations in the north-west of Western Australia, marking the beginning of a carefully organised strike that was to last for at least three years, but never officially ended.

The strike was more than a demand for better wages and conditions. It was, in the words of Keith Connolly in the Melbourne Herald, 'a well-considered statement by a grievously exploited people, standing up for their rights and dignity'.

How The West Was Lost tells the story of a shameful yet still largely unknown piece of Australia’s tangled history.

Screens with...

BREAD AND DRIPPING

A film by Vic Smith, Margot Nash, Elizabeth Schaffer, Wendy Brady and Donna Foster. Country: Australia, Rating: G, Run Time: 17 minutes, Language: English

Four women recount their lives during the bleak years of the Depression of the 1930s. Tibby Whalan, Eileen Pittman, Beryl Armstrong and Mary Wright describe their struggles to survive and maintain families when faced with widespread unemployment, evictions and hardship.

How The West Was Lost introduced by David Noakes and Rose Murray at Ritz Cinemas and Lido Cinemas. Bread and Dripping introduced by Vic Smith and Elizabeth Schaffer at Ritz Cinemas.

A discussion with David Noakes and Rose Murray will be held after the screening in the upstairs mezzanine at the Ritz in Sydney and in the discussion space off the foyer at the Lido in Melbourne.

This screening is dedicated to Heather Williams, producer, and to the great courage and determination of the Pilbara striker families.

‘In 1942, the old ones gathered at Skull Springs. By there they discussed life under the white man. They selected Clancy and Dooley to spread the word of the strike.’ – Jacob Oberdoo –Striker (and Associate Producer)

‘This is Dooley Bin Bin and this is Clancy McKenna. These two men made a strike to help us out from under the white man. Like white man has Captain Cook – white fella, we have these two men, strong men, they helped us out from under the white man for better living.’ – Billy Thomas – Striker.

‘The story of how we treated the Blackfellas is really the story of a criminal act. And although we made all sorts of arrangements and promises we never intended to keep any of them, nor did we.’ – Don McLeod – white supporter and co-organiser of the strike.

FILM NOTES ON HOW THE WEST WAS LOST

By Rose Murray and David Noakes

Rose Murray is a family member of the Pilbara striker families.

David Noakes is a documentary filmmaker, producer and executive producer.

THE FILMMAKERS

The documentary, How the West was Lost (1987), tells the story of the strike by Aboriginal station workers in the Pilbara that began in 1946.

The film was a collaborative process between filmmakers David Noakes (Director & Co-Producer), Heather Willams (Producer), Paul Roberts (Co-Writer and Associate Producer), Strelley Elder Jacob Oberdoo (Associate Producer), and Editor Frank Rijavec. It was shot by cinematographer Philip Bull. The Strelley Mob were also actively involved as collaborators in the making of the film.

** More information on the filmmakers below.

The film was a collaborative process between filmmakers David Noakes (Director & Co-Producer), Heather Willams (Producer), Paul Roberts (Co-Writer and Associate Producer), Strelley Elder Jacob Oberdoo (Associate Producer), and Editor Frank Rijavec. It was shot by cinematographer Philip Bull. The Strelley Mob were also actively involved as collaborators in the making of the film.

** More information on the filmmakers below.

THE FILM

I’m writing this in plain English. Many of the people who love this film don’t talk educated or flash English but they speak their own languages and Pilbara-style Aboriginal English. As a Nyangumarta woman I am responsible to my family and community when I talk about things that belong to us. This film, How the West was Lost, is very much part of us. It’s one of the ways we can share our history across communities to show how strong our people are. In today talk, we call it truth telling.

The importance of storytelling, song and dance in Aboriginal culture is well known. This is how we learn about caring for Country and our families. There are private stories meant for only a few and there are public ones meant for us all. This one is for everyone. Our culture really helped the Pilbara station workers take action. Getting the mob to agree to strike, through sitting down and talking is an important part of our old way. Marriage rules meant people could often speak two languages. Holding on to the Marrngu Law (Aboriginal Law) that’s shared across the Pilbara was most important. The strike involved many different language groups who had the same problems. To agree on walking off and working together, leaders and interpreters had to know how to talk and who to talk to.

Our way of life was smashed by the newcomers coming in from the coast looking for grazing land and coming in from the east making a stock route and searching for minerals. Our people were pushed away from water sources and grazing country. Children were being born from white fathers. New laws were put upon us. New animals with hard feet caused damage. The caretakers of Country no longer were free to do things, like using fire to keep the country healthy.

Stations needed workers for the animals, windmills and fencing. Work in the houses and gardens. Looking after babies and children was often done by Aboriginal girls and women. Some of those Aboriginal workers were valued by the non-Aboriginal families. But this didn’t mean it was shown in living conditions and pay, so they walked off.

Sometimes people just talk about the strike as 1946 to 1949. There’s a big push now to talk about those years because the offer was made about wages in 1949. I just remind them that the old people always said, ‘We’re still on strike’. A whole lot of our people never again worked for non-Aboriginal people under bad conditions.

How the West was Lost is a big film in many ways. I like the way the strikers told the story in song and acting out. You can tell that the filmmakers had no control sometimes. I loved that. I asked myself how did Marrngu (Aboriginal people) trust white people to do the right thing and show what happened “proper way”? The film was grown up by striker families at Strelley and Warralong stations, who first spent many hours sitting down with Paul Roberts, the Principal of their independent bilingual school. I don’t know how David Noakes and Paul got the final script together and the letters, telegrams, laws, poetry and newspaper articles to reach us English speakers. But I thank them, because we hear the story from all sides. The fact that the most senior Strelley leader signed off on the film and the community were satisfied was a very big deal and it shows.

Pilbara community mob watch the film with happiness and sadness. Many people on the film have passed away. Their strength, wisdom and love are sadly missed. The happiness comes from joining in and laughing at the funny bits. It’s a celebration of how we love acting out a good yarn. When I’ve sat down with family and friends to watch, I’ve often heard the word ‘japurtu’ and seen them shake their heads with sadness. This word is used when people are feeling sorry. A station worker’s life was rough and sometimes cruel but going on strike and working for a better future was hard work too.

When the old people in the film are telling the story, it’s the highlight of their life and they’re very proud of it. There was danger and they knew that standing up to the government and the coppers and the station that their children could be taken away. They knew that they lived under the harsh WA government laws. They knew that. They had seen my Mum, her niece and others stolen from them. Native welfare could send whole families far away. The film can only go for so long, it doesn’t show all of the leaders and all the stories. Some families will feel a bit left out. Many strikers worked with the filmmakers all the way through.

After watching the film, it stirs us up. Pilbara Aboriginal families start telling what our own family did during the strike or it makes us find out. Was your family helping the strikers when word came to the east coast? Did your family members work as Aboriginal “house girls”? I was brought up in Melbourne and took my Mum back, in 1978, to meet our family for the first time in forty years. I saw our mob running their own stations, holding big camp meetings and organising Law meetings. Old people were working hard to keep families together. Seeing the film for the first time really helped me understand this strength that old people showed in their changing world. We share the strike story to show our children the strength in standing up and working together.

This is a loved and valued film. We have always encouraged newcomers to the Pilbara to track it down. Having the strikers tell the story in their own way may not happen again. We’ve shown the film at a couple of big venues with David’s permission and it’s been just lovely. Pilbara mob have gotten up and told the story of their family being on strike. It’s really powerful. Perth people always say, ‘How come we weren’t told?’

I’m part of a group helping to share the story of the 1946 Strike in WA schools this year. The Strike and the How the West was Lost film will become better known in schools. I’m going to go to Cinema Reborn and support the Marrngu and other film makers who made it happen. All Australians need to know how important the strike is for today, not just yesterday.

Film note by Rose Murray

The importance of storytelling, song and dance in Aboriginal culture is well known. This is how we learn about caring for Country and our families. There are private stories meant for only a few and there are public ones meant for us all. This one is for everyone. Our culture really helped the Pilbara station workers take action. Getting the mob to agree to strike, through sitting down and talking is an important part of our old way. Marriage rules meant people could often speak two languages. Holding on to the Marrngu Law (Aboriginal Law) that’s shared across the Pilbara was most important. The strike involved many different language groups who had the same problems. To agree on walking off and working together, leaders and interpreters had to know how to talk and who to talk to.

Our way of life was smashed by the newcomers coming in from the coast looking for grazing land and coming in from the east making a stock route and searching for minerals. Our people were pushed away from water sources and grazing country. Children were being born from white fathers. New laws were put upon us. New animals with hard feet caused damage. The caretakers of Country no longer were free to do things, like using fire to keep the country healthy.

Stations needed workers for the animals, windmills and fencing. Work in the houses and gardens. Looking after babies and children was often done by Aboriginal girls and women. Some of those Aboriginal workers were valued by the non-Aboriginal families. But this didn’t mean it was shown in living conditions and pay, so they walked off.

Sometimes people just talk about the strike as 1946 to 1949. There’s a big push now to talk about those years because the offer was made about wages in 1949. I just remind them that the old people always said, ‘We’re still on strike’. A whole lot of our people never again worked for non-Aboriginal people under bad conditions.

How the West was Lost is a big film in many ways. I like the way the strikers told the story in song and acting out. You can tell that the filmmakers had no control sometimes. I loved that. I asked myself how did Marrngu (Aboriginal people) trust white people to do the right thing and show what happened “proper way”? The film was grown up by striker families at Strelley and Warralong stations, who first spent many hours sitting down with Paul Roberts, the Principal of their independent bilingual school. I don’t know how David Noakes and Paul got the final script together and the letters, telegrams, laws, poetry and newspaper articles to reach us English speakers. But I thank them, because we hear the story from all sides. The fact that the most senior Strelley leader signed off on the film and the community were satisfied was a very big deal and it shows.

Pilbara community mob watch the film with happiness and sadness. Many people on the film have passed away. Their strength, wisdom and love are sadly missed. The happiness comes from joining in and laughing at the funny bits. It’s a celebration of how we love acting out a good yarn. When I’ve sat down with family and friends to watch, I’ve often heard the word ‘japurtu’ and seen them shake their heads with sadness. This word is used when people are feeling sorry. A station worker’s life was rough and sometimes cruel but going on strike and working for a better future was hard work too.

When the old people in the film are telling the story, it’s the highlight of their life and they’re very proud of it. There was danger and they knew that standing up to the government and the coppers and the station that their children could be taken away. They knew that they lived under the harsh WA government laws. They knew that. They had seen my Mum, her niece and others stolen from them. Native welfare could send whole families far away. The film can only go for so long, it doesn’t show all of the leaders and all the stories. Some families will feel a bit left out. Many strikers worked with the filmmakers all the way through.

After watching the film, it stirs us up. Pilbara Aboriginal families start telling what our own family did during the strike or it makes us find out. Was your family helping the strikers when word came to the east coast? Did your family members work as Aboriginal “house girls”? I was brought up in Melbourne and took my Mum back, in 1978, to meet our family for the first time in forty years. I saw our mob running their own stations, holding big camp meetings and organising Law meetings. Old people were working hard to keep families together. Seeing the film for the first time really helped me understand this strength that old people showed in their changing world. We share the strike story to show our children the strength in standing up and working together.

This is a loved and valued film. We have always encouraged newcomers to the Pilbara to track it down. Having the strikers tell the story in their own way may not happen again. We’ve shown the film at a couple of big venues with David’s permission and it’s been just lovely. Pilbara mob have gotten up and told the story of their family being on strike. It’s really powerful. Perth people always say, ‘How come we weren’t told?’

I’m part of a group helping to share the story of the 1946 Strike in WA schools this year. The Strike and the How the West was Lost film will become better known in schools. I’m going to go to Cinema Reborn and support the Marrngu and other film makers who made it happen. All Australians need to know how important the strike is for today, not just yesterday.

Film note by Rose Murray

THE GENESIS AND MAKING OF THE FILM

On 1 May, 1946, station workers and their families in the Pilbara, Western Australia, took the audacious and brave decision to go on strike for better wages and living conditions, with hundreds joining from dozens of stations in the following months.

They were virtual slaves, receiving little or no pay and meagre rations for their long hours of work. They had no rights to land, to free movement, or to vote, and they were not counted as citizens in their own country. Workers described how they were forced to live no better than animals and were fed rotten meat on the woodheap.

The exploitation and abuse by white pastoralists, government agents, and legislators had gone on for decades. In the words of pastoralist and WA Premier (1890 – 1900), Sir John Forrest, in 1888, ‘many of us, including myself, would not be in the position we are in today without native labour on our sheep stations.’ (1)

Aboriginal leaders dreamed of a better life, and decided to strike after consulting Don McLeod, a white miner and fencing contractor, who was also disturbed by their entrenched inequality and mistreatment. He explained the actions open to the leaders to fight for their rights. They endured great hardship and physical danger, were harassed by the police, jailed and put in chains during their resistance, but stood firm and their bravery and determination finally forced changes that helped initiate the recognition of their rights.

While the strike is recognised by some as concluding in 1949, there was no official end and some old people claim still to be on strike today, as they never went back to work on the stations.

Today the community live on Strelley Station, one of the four they now own. At the time of filming, the story of the strike was little known. Unfortunately, that still remains the same.

Many of the filmmakers had read about the strike and were very honoured to be part of this important history telling. The film also followed the release of the book, How The West Was Lost (1984), written by Don McLeod, who was a white prospector who became a friend and confidant to those who would become the Strelley Mob.

The film was a collaborative filmmaking venture, which responded to a desire within the Strelley community for a film to be made about this significant – but often overlooked – event in the history of WA and Australia. In the 1980s when the film was made, the Strelley community of strikers and their families lived on a number of stations, running schools for their children where they taught their own languages and English. Paul Roberts was a teacher at the school, and he helped Don McLeod edit his book. Discussion around the book in the community led to the idea of making a film to at last tell the story of the strike.

Back in Perth, Paul talked with producer Heather Williams who approached David Noakes to direct the film. This filmmaking trio set about working with the community and seeking funding. Initial funding came from the Australian Film Commission (now Screen Australia) and the West Australian Film Council (now Screenwest) as well as the Strelley community. With some funding in place, Paul Roberts and David Noakes began the research stage of collecting stories and writing a script that carried the strikers’ stories. In May 1985, a crew, including director of photography, Phil Bull, began shooting the film.

It was always essential that the film would come about through close collaboration with the community, with Elders approving the script and confirming significant stories and locations where each story needed to be told.

In directing the film, David Noakes wanted to foreground the role of the Strelley community and also reflect the problematic issue of representing history. He wanted to intertwine the very raw and poignant re-enactments with the strikers telling their story of the strike, while foregrounding the present and the very act of storytelling. He had been struck by how an earlier film, Two Laws (Alessandro Cavadini and Carolyn Strachan, 1982), carried the power of oral history using re-enactment combined with history telling. Two Laws was shot in an ethnographic style, which allowed the essence of the oral tradition to be illustrated but left it with a narrow audience. The aim of How The West was Lost was to reach a wider audience and keep the power of the oral storytelling and authenticity of conscious re-enactment. This approach was more than met by the community, who were eager to step back in time and retell their stories using re-enactment and first-hand witness accounts by the surviving strikers.

Filming would occur in five-to-seven day blocks with the community deciding which sequences would be filmed next. In any block, the filmmakers and community would set off in trucks and four-wheel drives to the first location, which would be appropriate for a particular story. Often the filmmakers would arrive to find that the community were already dressing the set, lighting fires and creating the scenes that were required.

For this collaboration to be genuine, the stories and representation needed to be accurate. This made it imperative that early editing happen on site. The rushes – daily shot film – would be screened to the community every one to two weeks for further feedback. When shooting commenced, film editor Frank Rijavec joined the crew. He set up a film editing room at Strelley Station and the film began to take shape. The shoot lasted six weeks and Frank and David stayed on editing for a further five weeks, making sure the rough cut was correct and all translations accurate.

After the shoot and once the material was rough-cut, the filmmakers returned to Perth and began the task of raising the remainder of the funding. Editing continued over this time, along with the search for archival film and official correspondence from the original WA Department of Native Affairs. Early 16mm and some Super 8 footage from the ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s was sourced, adding a first-hand visual record of the work the station owners required of the Aboriginal workers.

In 1986, when completion money was confirmed, dramatisations of the government and church responses to the strike were shot in Perth, along with additional filming with the strikers in the Pilbara. By late 1986, the film was in the final stages of post-production. The producers worked with Perth musician, Ross Bolleter, to create music for the film that reflected the discord of the story. He was the perfect composer with the perfect instrument – the prepared piano (a piano that has had objects placed on or between its strings to change its sound). Bolleter’s fractured composition combines the melody of the double bass with the discord of the prepared piano to create a stark mood over the archival film of the 1929 One Hundred Year celebration of the “colonisation” of Western Australia. He is joined on the score by Phillip Kakulas (double bass) and Mark Kain (saxophone and percussion), creating an original and striking soundtrack.

The film juxtaposes the community’s oral history with the exactitude of bureaucratic speak from the era: the colonists stamping their ownership on the land and state. The human story of the strikers provides a sharp contrast: people telling their story from their Country. The strikers take charge of the film’s dramatisations, foregrounding their control of the story and their history.

The premiere screening was held in the creek bed where the Skull Springs scenes were shot. Everyone gathered there, fires were lit, damper and tea made and the film screened. Many people were speechless after… and the word came back they were happy. This screening was followed by a week’s run at the Festival of Perth in 1987.

The Festival of Perth was considered then to be a conservative festival, so the filmmakers were very pleased and surprised the film was chosen to screen at the Windsor Cinema in the suburb where former premier Charlie Court and many retired squatters lived. The audiences were very strong but there was a noticeable hush at the end of the film.

How The West Was Lost was released theatrically throughout Australia, and went on to win a number of prestigious awards, including the inaugural Human Rights Documentary Film Award, and the Special Jury Prize at the Hawaii International Film Festival. It received five nominations in the 1987 AFI, including Best Film and Best Cinematogrphy. It also screened at the following festivals: Nyon Film Festival, Leipzig International Film Festival, Edinburgh Film Festival and IFP Market 1987.

Notes

Film note by David Noakes

They were virtual slaves, receiving little or no pay and meagre rations for their long hours of work. They had no rights to land, to free movement, or to vote, and they were not counted as citizens in their own country. Workers described how they were forced to live no better than animals and were fed rotten meat on the woodheap.

The exploitation and abuse by white pastoralists, government agents, and legislators had gone on for decades. In the words of pastoralist and WA Premier (1890 – 1900), Sir John Forrest, in 1888, ‘many of us, including myself, would not be in the position we are in today without native labour on our sheep stations.’ (1)

Aboriginal leaders dreamed of a better life, and decided to strike after consulting Don McLeod, a white miner and fencing contractor, who was also disturbed by their entrenched inequality and mistreatment. He explained the actions open to the leaders to fight for their rights. They endured great hardship and physical danger, were harassed by the police, jailed and put in chains during their resistance, but stood firm and their bravery and determination finally forced changes that helped initiate the recognition of their rights.

While the strike is recognised by some as concluding in 1949, there was no official end and some old people claim still to be on strike today, as they never went back to work on the stations.

Today the community live on Strelley Station, one of the four they now own. At the time of filming, the story of the strike was little known. Unfortunately, that still remains the same.

Many of the filmmakers had read about the strike and were very honoured to be part of this important history telling. The film also followed the release of the book, How The West Was Lost (1984), written by Don McLeod, who was a white prospector who became a friend and confidant to those who would become the Strelley Mob.

The film was a collaborative filmmaking venture, which responded to a desire within the Strelley community for a film to be made about this significant – but often overlooked – event in the history of WA and Australia. In the 1980s when the film was made, the Strelley community of strikers and their families lived on a number of stations, running schools for their children where they taught their own languages and English. Paul Roberts was a teacher at the school, and he helped Don McLeod edit his book. Discussion around the book in the community led to the idea of making a film to at last tell the story of the strike.

Back in Perth, Paul talked with producer Heather Williams who approached David Noakes to direct the film. This filmmaking trio set about working with the community and seeking funding. Initial funding came from the Australian Film Commission (now Screen Australia) and the West Australian Film Council (now Screenwest) as well as the Strelley community. With some funding in place, Paul Roberts and David Noakes began the research stage of collecting stories and writing a script that carried the strikers’ stories. In May 1985, a crew, including director of photography, Phil Bull, began shooting the film.

It was always essential that the film would come about through close collaboration with the community, with Elders approving the script and confirming significant stories and locations where each story needed to be told.

In directing the film, David Noakes wanted to foreground the role of the Strelley community and also reflect the problematic issue of representing history. He wanted to intertwine the very raw and poignant re-enactments with the strikers telling their story of the strike, while foregrounding the present and the very act of storytelling. He had been struck by how an earlier film, Two Laws (Alessandro Cavadini and Carolyn Strachan, 1982), carried the power of oral history using re-enactment combined with history telling. Two Laws was shot in an ethnographic style, which allowed the essence of the oral tradition to be illustrated but left it with a narrow audience. The aim of How The West was Lost was to reach a wider audience and keep the power of the oral storytelling and authenticity of conscious re-enactment. This approach was more than met by the community, who were eager to step back in time and retell their stories using re-enactment and first-hand witness accounts by the surviving strikers.

Filming would occur in five-to-seven day blocks with the community deciding which sequences would be filmed next. In any block, the filmmakers and community would set off in trucks and four-wheel drives to the first location, which would be appropriate for a particular story. Often the filmmakers would arrive to find that the community were already dressing the set, lighting fires and creating the scenes that were required.

For this collaboration to be genuine, the stories and representation needed to be accurate. This made it imperative that early editing happen on site. The rushes – daily shot film – would be screened to the community every one to two weeks for further feedback. When shooting commenced, film editor Frank Rijavec joined the crew. He set up a film editing room at Strelley Station and the film began to take shape. The shoot lasted six weeks and Frank and David stayed on editing for a further five weeks, making sure the rough cut was correct and all translations accurate.

After the shoot and once the material was rough-cut, the filmmakers returned to Perth and began the task of raising the remainder of the funding. Editing continued over this time, along with the search for archival film and official correspondence from the original WA Department of Native Affairs. Early 16mm and some Super 8 footage from the ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s was sourced, adding a first-hand visual record of the work the station owners required of the Aboriginal workers.

In 1986, when completion money was confirmed, dramatisations of the government and church responses to the strike were shot in Perth, along with additional filming with the strikers in the Pilbara. By late 1986, the film was in the final stages of post-production. The producers worked with Perth musician, Ross Bolleter, to create music for the film that reflected the discord of the story. He was the perfect composer with the perfect instrument – the prepared piano (a piano that has had objects placed on or between its strings to change its sound). Bolleter’s fractured composition combines the melody of the double bass with the discord of the prepared piano to create a stark mood over the archival film of the 1929 One Hundred Year celebration of the “colonisation” of Western Australia. He is joined on the score by Phillip Kakulas (double bass) and Mark Kain (saxophone and percussion), creating an original and striking soundtrack.

The film juxtaposes the community’s oral history with the exactitude of bureaucratic speak from the era: the colonists stamping their ownership on the land and state. The human story of the strikers provides a sharp contrast: people telling their story from their Country. The strikers take charge of the film’s dramatisations, foregrounding their control of the story and their history.

The premiere screening was held in the creek bed where the Skull Springs scenes were shot. Everyone gathered there, fires were lit, damper and tea made and the film screened. Many people were speechless after… and the word came back they were happy. This screening was followed by a week’s run at the Festival of Perth in 1987.

The Festival of Perth was considered then to be a conservative festival, so the filmmakers were very pleased and surprised the film was chosen to screen at the Windsor Cinema in the suburb where former premier Charlie Court and many retired squatters lived. The audiences were very strong but there was a noticeable hush at the end of the film.

How The West Was Lost was released theatrically throughout Australia, and went on to win a number of prestigious awards, including the inaugural Human Rights Documentary Film Award, and the Special Jury Prize at the Hawaii International Film Festival. It received five nominations in the 1987 AFI, including Best Film and Best Cinematogrphy. It also screened at the following festivals: Nyon Film Festival, Leipzig International Film Festival, Edinburgh Film Festival and IFP Market 1987.

Notes

- Quote from Western Australian Parliamentary Debate (W.A.P.D), 19 November 1888, p. 322, Sir John Forrest, Pastoralist, WA Premier 1890 – 1900).

Film note by David Noakes

THE RESTORATION

Restored in 2024 by Piccolo Films from the

original 16mm camera negative and master audio components. Restoration by Ray

Argall in consultation with David Noakes.

Director: David Noakes; Production Company: Friends Film Productions and Market Street Films Ltd; Producers: Heather Williams, David Noakes; Script: David Noakes, Paul Roberts; Photography: Philip Bull; Editor: Frank Rijavek; Music Improvised and Performed by: Ross Bolleter, Phillip Kakulas, Mark Kain

Produced with financial assistance from the Creative Development Fund, Australian Film Commission, Aboriginal Arts Board, Australia Council, Nomads 1996 Pty Ltd, Western Australian Film Council, Aboriginal Affairs Planning Council (WA)

Made with production assistance from, and in consultation with, the Nomads Group, Pilbara Region, Western Australia

Australia | 1987 | 72 Mins | 4K DCP | Colour | English | G

The Filmmakers:

Heather Williams, Producer (1960 – 2023), was a huge force within the West Australian filmmaking community: a passionate and persistent worker who helped realise the creative visions of many, as producer, mentor and supporter. She also produced her own film projects, including Just Friends (1982), Steps of Light (1983), Wonderland (1986), A Little Life (1988), Tokyo Rose North (1987), and How The West was Lost.

David Noakes, Director, Co-Producer and Co-Writer, began making documentary films in the late 1970s through his company, Market Street Films, based in Fremantle. In 1987 he directed and co-produced How The West was Lost. In 1988 David was awarded an ABC/Australian Film Commission Documentary Fellowship, which provided the opportunity to make the film Bigger Than Texas (1992), a hybrid personal essay and documentary film about the history of WA. David’s other documentary producing credits include Shadow of the Shark (2002), The Trouble with Merle (2002), and Ted’s Evolution (2003). David held senior roles at the Australian Film Commission and later the Film Finance Corporation, and as Sydney Manager for the National Film and Sound Archive. He is currently a Committee Member of the ACT Government Film Investment Fund.

Since 2008 David has worked as Production Executive at First Australian Completion Bond Company on over 100 Australian film and television productions spanning drama, animation and documentary. He continues to work as an Executive Producer, most recently on the series Black As (2016-), and the documentary feature, I am No Bird (2019), and as Executive Producer for the WA feature film, End To End (2022).

Paul Roberts, Co-Writer and Associate Producer, has worked in film and television for over thirty years. His film life began with How the West was Lost. Prior to the film, Paul worked for three years as a teacher at the Strelley School. Paul’s knowledge and close relationship to the community made his contribution to the filmmaking process essential. His experience with How The West was Lost then led Paul to produce and direct a significant collection of films which focus on and examine the lives and intersection of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australia. His credits include Black Magic (1988), Something Close to Hell (1989), Mili Milli, Artists Up Front (1997), Buffalo Legends (1997), Surviving: Stories of Belonging, and the series Life of the Town (2009).

Jacob Oberdoo, Associate Producer (1910 – 1990) was, at the time of making How the West was Lost, one of the most senior lawmen amongst the Nyangumarta speakers and within the Strelley Mob, some of the strikers and their descendants who owned Strelley station. Jacob was a strong man who never wavered in his opposition to the notion that Aboriginal people had ceded control of their land. In 1972, when advised by the Queen that she intended to award him The British Empire Medal, he wrote back declining her offer, saying, ‘It is clear you are ignorant of the fact that I am a Law Carrier of the Rule of Law and as such I am unable to do business or accept favours with Law Carriers in Bad Standing.’

Jacob represented his people on many occasions, including at the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement conference in Brisbane in 1961. There, to a mainly stunned white audience, he shared the story of the strike and how it allowed them independence through mining and other ventures. Jacob was a significant driver behind the making of the film. He was a gentle giant with immense gravitas and an unwavering conviction to fight for his people.

Frank Rijavec, Film Editor, is an award-winning filmmaker and media/communications researcher whose work encompasses the development of community-based, participatory media, and documentary production for education and public television. Frank’s work on How the West was Lost received a nomination for Best Editing at the Australian Film Institute Awards. His film credits include the documentaries, The Last Stand, Skin of the Earth (1988), Black Magic (1988), Requiem for a Generation of Lost Souls (1996), and The Habits of New Norcia (2000). His landmark feature documentary, Exile and the Kingdom (1993), was made with the Yindjibarndi and Ngarluma people and won many awards.

Since 2004, Frank has worked in collaboration with Aboriginal organisations in the Pilbara and on WA’s south coast, training Indigenous media practitioners in cultural recording and documentary projects. In 2010, Frank was awarded a PhD for Sovereign Voices, his thesis on the Yindjibarndi fight for a dignified life amid the Pilbara resources boom. Most recently, Frank completed, as Director, Editor and Director of Photography, Genocide in the Wildflower State (2024).

Philip Bull, Cinematographer, started his long and accomplished career as a cinematographer and director in WA. He has shot many significant documentaries, including On the Edge of the Forest (1980); Backs to the Blast: An Australian Nuclear Story (1980); South of the Border, State of Shock (1989); Nazi SuperGrass (1993); Secrets of the Jury Room (2004); Besieged: The Ned Kelly Story (2004); Kindness of Strangers (2006); and How the West was Lost (1987). His work in television includes lead cinematographer on the long-running series Bondi Rescue, How to Grow a Planet andWanted. Philip’s work has taken him all over the world, to war zones and the remotest of places. The new restoration of How the West was Lost shows Bull’s fine photography: his eye never misses the important moments.

Notes compiled from How the West was Lost press kit

Director: David Noakes; Production Company: Friends Film Productions and Market Street Films Ltd; Producers: Heather Williams, David Noakes; Script: David Noakes, Paul Roberts; Photography: Philip Bull; Editor: Frank Rijavek; Music Improvised and Performed by: Ross Bolleter, Phillip Kakulas, Mark Kain

Produced with financial assistance from the Creative Development Fund, Australian Film Commission, Aboriginal Arts Board, Australia Council, Nomads 1996 Pty Ltd, Western Australian Film Council, Aboriginal Affairs Planning Council (WA)

Made with production assistance from, and in consultation with, the Nomads Group, Pilbara Region, Western Australia

Australia | 1987 | 72 Mins | 4K DCP | Colour | English | G

The Filmmakers:

Heather Williams, Producer (1960 – 2023), was a huge force within the West Australian filmmaking community: a passionate and persistent worker who helped realise the creative visions of many, as producer, mentor and supporter. She also produced her own film projects, including Just Friends (1982), Steps of Light (1983), Wonderland (1986), A Little Life (1988), Tokyo Rose North (1987), and How The West was Lost.

David Noakes, Director, Co-Producer and Co-Writer, began making documentary films in the late 1970s through his company, Market Street Films, based in Fremantle. In 1987 he directed and co-produced How The West was Lost. In 1988 David was awarded an ABC/Australian Film Commission Documentary Fellowship, which provided the opportunity to make the film Bigger Than Texas (1992), a hybrid personal essay and documentary film about the history of WA. David’s other documentary producing credits include Shadow of the Shark (2002), The Trouble with Merle (2002), and Ted’s Evolution (2003). David held senior roles at the Australian Film Commission and later the Film Finance Corporation, and as Sydney Manager for the National Film and Sound Archive. He is currently a Committee Member of the ACT Government Film Investment Fund.

Since 2008 David has worked as Production Executive at First Australian Completion Bond Company on over 100 Australian film and television productions spanning drama, animation and documentary. He continues to work as an Executive Producer, most recently on the series Black As (2016-), and the documentary feature, I am No Bird (2019), and as Executive Producer for the WA feature film, End To End (2022).

Paul Roberts, Co-Writer and Associate Producer, has worked in film and television for over thirty years. His film life began with How the West was Lost. Prior to the film, Paul worked for three years as a teacher at the Strelley School. Paul’s knowledge and close relationship to the community made his contribution to the filmmaking process essential. His experience with How The West was Lost then led Paul to produce and direct a significant collection of films which focus on and examine the lives and intersection of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australia. His credits include Black Magic (1988), Something Close to Hell (1989), Mili Milli, Artists Up Front (1997), Buffalo Legends (1997), Surviving: Stories of Belonging, and the series Life of the Town (2009).

Jacob Oberdoo, Associate Producer (1910 – 1990) was, at the time of making How the West was Lost, one of the most senior lawmen amongst the Nyangumarta speakers and within the Strelley Mob, some of the strikers and their descendants who owned Strelley station. Jacob was a strong man who never wavered in his opposition to the notion that Aboriginal people had ceded control of their land. In 1972, when advised by the Queen that she intended to award him The British Empire Medal, he wrote back declining her offer, saying, ‘It is clear you are ignorant of the fact that I am a Law Carrier of the Rule of Law and as such I am unable to do business or accept favours with Law Carriers in Bad Standing.’

Jacob represented his people on many occasions, including at the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement conference in Brisbane in 1961. There, to a mainly stunned white audience, he shared the story of the strike and how it allowed them independence through mining and other ventures. Jacob was a significant driver behind the making of the film. He was a gentle giant with immense gravitas and an unwavering conviction to fight for his people.

Frank Rijavec, Film Editor, is an award-winning filmmaker and media/communications researcher whose work encompasses the development of community-based, participatory media, and documentary production for education and public television. Frank’s work on How the West was Lost received a nomination for Best Editing at the Australian Film Institute Awards. His film credits include the documentaries, The Last Stand, Skin of the Earth (1988), Black Magic (1988), Requiem for a Generation of Lost Souls (1996), and The Habits of New Norcia (2000). His landmark feature documentary, Exile and the Kingdom (1993), was made with the Yindjibarndi and Ngarluma people and won many awards.

Since 2004, Frank has worked in collaboration with Aboriginal organisations in the Pilbara and on WA’s south coast, training Indigenous media practitioners in cultural recording and documentary projects. In 2010, Frank was awarded a PhD for Sovereign Voices, his thesis on the Yindjibarndi fight for a dignified life amid the Pilbara resources boom. Most recently, Frank completed, as Director, Editor and Director of Photography, Genocide in the Wildflower State (2024).

Philip Bull, Cinematographer, started his long and accomplished career as a cinematographer and director in WA. He has shot many significant documentaries, including On the Edge of the Forest (1980); Backs to the Blast: An Australian Nuclear Story (1980); South of the Border, State of Shock (1989); Nazi SuperGrass (1993); Secrets of the Jury Room (2004); Besieged: The Ned Kelly Story (2004); Kindness of Strangers (2006); and How the West was Lost (1987). His work in television includes lead cinematographer on the long-running series Bondi Rescue, How to Grow a Planet andWanted. Philip’s work has taken him all over the world, to war zones and the remotest of places. The new restoration of How the West was Lost shows Bull’s fine photography: his eye never misses the important moments.

Notes compiled from How the West was Lost press kit

FILM NOTES ON BREAD AND DRIPPING

By Vic Smith and Elizabeth Schaffer

By Vic Smith and Elizabeth Schaffer

Elizabeth Schaffer has a professional background in education and public history.

Vic Smith’s film credits include Editing Assistant, For Love or Money (1983) and Assistant Editor, On Guard (1984).

WIMMINSFILMS

Bread and Dripping was made by the collective, Wimminsfilms – Vic Smith, Margot Nash, Elizabeth Schaffer, Donna Foster and Wendy Brady.

The film was developed in the context of feminism and the increased activity of women in filmmaking in the 1970s and 80s. The Sydney Women’s Film Group, which operated out of the Sydney Filmmakers Co-op, was a focal point for discussion around feminism and film. Actively working to support the creation, distribution and exhibition of films made by women that gave voice to women’s stories, the group organised workshops that provided women with access to filmmaking skills. While attending a Women’s Film Workshop, four young women with little previous experience in filmmaking came together around an idea for a documentary exploring the experience of the Great Depression in Australia from the point of view of women who had lived through it. These women, Vic Smith, Elizabeth Schaffer, Donna Foster and Wendy Brady, formed a production company called Wimminsfilms and applied successfully to the Creative Development Branch of the Australian Film Commission and the Women’s Film Fund to develop the documentary that became Bread and Dripping.

At every stage in the development of Bread and Dripping, filmmaking tasks were shared, including the research, fundraising, production and post-production. During filming the roles of director, camera operator, sound recordist and interviewer were rotated across the collective. Many months were spent searching for images and archival footage of women's lives in the 1930s. Margot Nash, who was initially engaged as a professional advisor during filming, went on to take a major role in editing the documentary, becoming part of the Wimminsfilms collective during this period.

The film was developed in the context of feminism and the increased activity of women in filmmaking in the 1970s and 80s. The Sydney Women’s Film Group, which operated out of the Sydney Filmmakers Co-op, was a focal point for discussion around feminism and film. Actively working to support the creation, distribution and exhibition of films made by women that gave voice to women’s stories, the group organised workshops that provided women with access to filmmaking skills. While attending a Women’s Film Workshop, four young women with little previous experience in filmmaking came together around an idea for a documentary exploring the experience of the Great Depression in Australia from the point of view of women who had lived through it. These women, Vic Smith, Elizabeth Schaffer, Donna Foster and Wendy Brady, formed a production company called Wimminsfilms and applied successfully to the Creative Development Branch of the Australian Film Commission and the Women’s Film Fund to develop the documentary that became Bread and Dripping.

At every stage in the development of Bread and Dripping, filmmaking tasks were shared, including the research, fundraising, production and post-production. During filming the roles of director, camera operator, sound recordist and interviewer were rotated across the collective. Many months were spent searching for images and archival footage of women's lives in the 1930s. Margot Nash, who was initially engaged as a professional advisor during filming, went on to take a major role in editing the documentary, becoming part of the Wimminsfilms collective during this period.

THE FILM

In Bread and Dripping (released in 1982), four women recount their lives during the bleak years of the economic depression of the 1930s. Tibby Whalan, Eileen Pittman, Beryl Armstrong and Mary Wright describe their struggles to survive and maintain families when faced with widespread unemployment, evictions and hardship. The film makes extensive use of archival footage and photographs from the 1930s, presenting a unique insight into the lives of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous women in Australia. The title, Bread and Dripping, refers to a meal of leftover fat soaked in bread and eaten when no other food was available.

Taking the experience of women during the Great Depression as its focus, Bread and Dripping aimed to learn directly from women themselves, through their stories of survival and growth in extraordinary times. Through networks of family and friends; interviews conducted with writers and academics such as Kylie Tennant, Nadia Wheatley and Wendy Lowenstein; and in meetings with women who had been active in trade unions and women’s organisations from the 1930s, the filmmakers built up a rich picture of women’s lives at a time of major economic and social crisis. Eventually the stories shared by four women emerged as representative of the struggles of so many women during the period.

Bread and Dripping premiered at Melbourne Film Festival in 1982. It went on to be shown around the world at national and international film festivals, on television, in schools, trade unions and in community settings around Australia. It continues to be a rare and powerful insight into women’s lives. In the film, four women sharing their personal recollections of struggle and survival during the Great Depression. When viewed from the perspective of out current era of global economic and social crisis, the film gives a timely and powerful insight into ways that women experience and shoulder the impacts of social and economic upheaval.

Taking the experience of women during the Great Depression as its focus, Bread and Dripping aimed to learn directly from women themselves, through their stories of survival and growth in extraordinary times. Through networks of family and friends; interviews conducted with writers and academics such as Kylie Tennant, Nadia Wheatley and Wendy Lowenstein; and in meetings with women who had been active in trade unions and women’s organisations from the 1930s, the filmmakers built up a rich picture of women’s lives at a time of major economic and social crisis. Eventually the stories shared by four women emerged as representative of the struggles of so many women during the period.

Bread and Dripping premiered at Melbourne Film Festival in 1982. It went on to be shown around the world at national and international film festivals, on television, in schools, trade unions and in community settings around Australia. It continues to be a rare and powerful insight into women’s lives. In the film, four women sharing their personal recollections of struggle and survival during the Great Depression. When viewed from the perspective of out current era of global economic and social crisis, the film gives a timely and powerful insight into ways that women experience and shoulder the impacts of social and economic upheaval.

THE RESTORATION

Bread and Dripping was digitally restored in 2K from

the original 16mm A&B roll negatives and sound mix, by Ray Argall from

Piccolo Films in consultation with Margot Nash and Vic Smith. All the original

materials are held in the National Film and Sound Archive Australia.

A film by Vic Smith, Margot Nash, Elizabeth Schaffer, Donna Foster and Wendy Brady. Produced with the Assistance of the Australian Film Commission and the Women’s Film Fund,

Australia | 1982 | 17 Mins | 2K DCP | Colour | English | G

A film by Vic Smith, Margot Nash, Elizabeth Schaffer, Donna Foster and Wendy Brady. Produced with the Assistance of the Australian Film Commission and the Women’s Film Fund,

Australia | 1982 | 17 Mins | 2K DCP | Colour | English | G