BLACK GIRL (1966)

12:45PM, Saturday April 29

12:30PM, Monday May 01

Randwick Ritz

Director: Ousmane Sembène

Country: France, Senegal

Year: 1966

Runtime (Black Girl): 65 minutes

Full Runtime including shorts: 107 minutes

Rating: U15+

Language: French, Wolof, English subtitles

TICKETS ⟶

12:30PM, Monday May 01

Randwick Ritz

Director: Ousmane Sembène

Country: France, Senegal

Year: 1966

Runtime (Black Girl): 65 minutes

Full Runtime including shorts: 107 minutes

Rating: U15+

Language: French, Wolof, English subtitles

TICKETS ⟶

BLACK GIRL/ LA NOIRE DE

AUSTRALIAN PREMIERE OF THE 4K RESTORATION

SCREENS WITH THE SHORT FILMS BOROM SARRET (1963) & CONTRAS CITY (1969) (4K)

"As Westerners, we begin the movie thinking we're watching Africans, but we realise Africans like Sembène have been watching us, too, and know us far better than we know them.” – John Powers, National Public Radio

A Senegalese woman is working for a French colonial couple in a villa in Dakar, when they offer to take her to Antibes, on the French Riviera. She is distressed to find herself isolated in a high-rise apartment, cooking and cleaning and being treated as both an exotic trophy and a slave. Often referred to as the ‘father of African cinema’ Ousmane Sembène – who was also a celebrated novelist - made nine feature films during his forty-year career, most of them dealing with colonialism, religion and African women. 4K restoration.

“A razor-sharp dissection of colonialist condescension and dehumanization.” — Emmet Sweeney

“Black Girl has also proved prophetic. With the rise of globalization, millions of women from poor countries have migrated to the global north to become domestic workers.” — Girish Shambu. Film Comment

Screens with Sembène’s restored short film The Wagoner/Borom Sarret (1963) and with Djibril Diop Mambety’s remarkable short documentary on life in the Senegalese capital Dakar Contras City (1969, 4K).

Contras City | Djibril Diop MAMBÉTY | Senegal | 1968 | 18 mins. | 2K Flat DCP (orig. 35mm, 1.37:1) | B&W | Mono Sd. | Wolof withEng. subtitles | U/C15+

A fictional documentary that portrays the city of Dakar, Senegal, as we hear th conversation between a Senegalese man (the director, Djibril Diop Mambéty) an a French woman, Inge Hirschnitz.

Borom Sarret | Ousmane SEMBÈNE | Senegal, France | 1963 | 18 mins. | 2K Flat DCP (orig. 35mm, 1.37:1) | B&W | Mono Sd. | French, Wolof with Eng. subtitles | U/C15+.

A young cart driver in Dakar is robbed by a succession of dishonest passengers. When his cart is confiscated by the police, he loses not only his means of livelihood but his sole claim to self-respect in an exploited and poverty-ridden community.

The 12:45pm screening on Saturday 29 April will be introduced by video introduction by Samba Gadjigo. Samba Gadjigo is Helen Day Gould Professor of French at Mount Holyoke College, Massachusetts. His research focuses on French-speaking Africa, particularly the work of filmmaker Ousmane Sembene. His 2015 documentary, Sembene!, co-directed by Jason Silverman, is a biopic focusing on Sembene’s life and work, exploring the themes developed in the biography through interviews and extensive footage from Senegal, Burkina Faso, and France. In 2016, Samba received the Faculty Award for Scholarship in recognition of his “international, multi-disciplinary career—a career throughout which his own story-telling has merged with that of Sembene’s, interweaving African literature, film, history, politics, and indeed these with language and with life itself.” His writing has appeared in African Cinema and Human Rights, Research in African Literatures, and Contributions in Black Studies.

Watch a superb video essay about Ousmane Sembène and Black Girl here.

AUSTRALIAN PREMIERE OF THE 4K RESTORATION

SCREENS WITH THE SHORT FILMS BOROM SARRET (1963) & CONTRAS CITY (1969) (4K)

"As Westerners, we begin the movie thinking we're watching Africans, but we realise Africans like Sembène have been watching us, too, and know us far better than we know them.” – John Powers, National Public Radio

A Senegalese woman is working for a French colonial couple in a villa in Dakar, when they offer to take her to Antibes, on the French Riviera. She is distressed to find herself isolated in a high-rise apartment, cooking and cleaning and being treated as both an exotic trophy and a slave. Often referred to as the ‘father of African cinema’ Ousmane Sembène – who was also a celebrated novelist - made nine feature films during his forty-year career, most of them dealing with colonialism, religion and African women. 4K restoration.

“A razor-sharp dissection of colonialist condescension and dehumanization.” — Emmet Sweeney

“Black Girl has also proved prophetic. With the rise of globalization, millions of women from poor countries have migrated to the global north to become domestic workers.” — Girish Shambu. Film Comment

Screens with Sembène’s restored short film The Wagoner/Borom Sarret (1963) and with Djibril Diop Mambety’s remarkable short documentary on life in the Senegalese capital Dakar Contras City (1969, 4K).

Contras City | Djibril Diop MAMBÉTY | Senegal | 1968 | 18 mins. | 2K Flat DCP (orig. 35mm, 1.37:1) | B&W | Mono Sd. | Wolof withEng. subtitles | U/C15+

A fictional documentary that portrays the city of Dakar, Senegal, as we hear th conversation between a Senegalese man (the director, Djibril Diop Mambéty) an a French woman, Inge Hirschnitz.

Borom Sarret | Ousmane SEMBÈNE | Senegal, France | 1963 | 18 mins. | 2K Flat DCP (orig. 35mm, 1.37:1) | B&W | Mono Sd. | French, Wolof with Eng. subtitles | U/C15+.

A young cart driver in Dakar is robbed by a succession of dishonest passengers. When his cart is confiscated by the police, he loses not only his means of livelihood but his sole claim to self-respect in an exploited and poverty-ridden community.

The 12:45pm screening on Saturday 29 April will be introduced by video introduction by Samba Gadjigo. Samba Gadjigo is Helen Day Gould Professor of French at Mount Holyoke College, Massachusetts. His research focuses on French-speaking Africa, particularly the work of filmmaker Ousmane Sembene. His 2015 documentary, Sembene!, co-directed by Jason Silverman, is a biopic focusing on Sembene’s life and work, exploring the themes developed in the biography through interviews and extensive footage from Senegal, Burkina Faso, and France. In 2016, Samba received the Faculty Award for Scholarship in recognition of his “international, multi-disciplinary career—a career throughout which his own story-telling has merged with that of Sembene’s, interweaving African literature, film, history, politics, and indeed these with language and with life itself.” His writing has appeared in African Cinema and Human Rights, Research in African Literatures, and Contributions in Black Studies.

Watch a superb video essay about Ousmane Sembène and Black Girl here.

FILM NOTES

By Hamish Ford

Ousmane Sembène

The great Senegalese writer and director Ousmane Sembène (1923-2007) is the most important and discussed of all African filmmakers, commonly credited with being the first director from the continent to make both a feature, La Noire de…/Black Girl (1966), and perhaps even any film, the 19-minute Borom Sarret (1963). Initially coming to prominence within Francophone culture as a novelist in 1960 with the celebrated Les bouts de bois de Dieu/God’s Bits of Wood, an anti-colonial story based on a 1947 Senegal railway strike in which he had participated, Sembène was well aware that by writing in French and unable to use his home country’s local Wolof (a non-tonal language without standardised or indigenous written forms), he was speaking only to Francophone European and bourgeois colonial African audiences – a reality that did not sit well with the author’s communist politics. This motivated an extended trip to Moscow in 1962-3 to learn filmmaking at the Gorky Film Studio under Mark Donskoy, so that his characters and work could communicate to local audiences via the spoken word. The result was a stunningly original and influential mode of filmmaking spanning ten features plus shorts combining self-conscious realist, expressionist, and modernist tendencies, powered by a Marxist vision and generative anger at colonial and postcolonial realities.

La Noire de… is one of the founding gems of a genuine world cinema’s initial post-colonial chapter, a series of films by directors from recently independent former colonies (or working from Europe as exiles) and other typically poor non-Western countries that essay the ongoing effects of such history. If European cinema of the early-mid 1960s is justly celebrated for its modernist aesthetics and formal consolidation, throughout the second half of the decade Sembène and these other non-Western directors from the ‘second’ (communist bloc) or ‘third’ worlds offered fresh formal-stylistic approaches and entirely new perspectives often marked by radically internationalist visions and Marxist critique. The result was not only a substantive deepening of cinema’s already glorious 1960s story, but a first rush of what film scholars now call ‘political modernism’ that both predates more famous (to Western centric eyes and minds) leftist European films of the 1968–‘75 period while also forcing into being the very concept, reality, and unfinished challenge of ‘world cinema’. No-one is more central to both this history and, even more obviously, filmmaking on his home continent than Ousmane Sembène. While much has been written on his life and work over a long period of time, especially in France – considering the frequent Euro-centric nature of film commentary in the West – Sembène’s achievements and contribution to cinema history are only just starting to be reckoned with beyond the filmmaker’s long-dedicated following.

Black Girl (1966)

Commentators have long cited Sembène’s

filmmaking as a cinematic version of the griot(a kind of traditional West African bard or troubadour). In this understanding,

a precise historical reality is rendered on screen – providing a realist

materiality – accompanied by inherently ‘reflexive’ commentary that analyses

any such reality via a loose, self-conscious narration via a voice-over by one

of the characters at the centre or edge of the story, or more subtly Sembène’s own authorial voice, avoiding the well-known pitfalls of ‘objectivity’.

Closely connected to this idea is the role and importance of linguistic

specificity, diversity, and enunciation. Following La Noire de…, Sembène would

insist – in keeping with his founding motivation to become a filmmaker – on

using appropriate language, so

that his stories and political essaying could be narrated in a proper (local)

tongue. That his debut feature does not follow this principle is

important to note. Co-production realities were likely such that La Noire de… could only be made if

spoken in French. Nevertheless, the apparent compromising of such a key

principle for his first film can appear to undermine its purpose. Viewers may indeed

be easily confused when the protagonist, Diouana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop), is

described by her new French employers during a lunch with friends as not

speaking French when we have heard her do exactly this in her extensive ‘interior’

voice-over narration both in France and during flashbacks to her life in

Senegal, not to mention that she appears to understand their instructions.

The on-paper flaw of its French soundtrack ultimately gives La Noire de… a generative, reflexive touch, a kind of ‘scar’ marking the material and thereby also ideological reality of an African director making a film part-set in Africa. Offering in the process a basic point of political economy and how the market operates by way of a gravitational pull born of colonial history and its ongoing impacts (while this film was made half a decade into Senegal’s official independence, Sembène would later mount a merciless satirical attack on the postcolonial regime’s subservience of France and the capitalist West in his 1975 black comedy, Xala), the frequently glaring inappropriateness of its dubbed French-language soundtrack works to further problematise any ‘realist’ aesthetics that may be assumed in light of the director’s training and politics. To make the effect even more striking, not only is Diouana’s voice dubbed (by Haitian singer Toto Bissainthe) but so are those of the actors playing her French employers. This linguistic aspect only reinforces the film’s other stylistic elements to suggest a presentational, elliptical, and loose modernist sensibility rather than a more representational or realist one.

The original French title of the film, La noire de… refers to a subject as owned or bought by somebody, making clear in three words and suggestive ellipses that this film is about fundamental connections between colonial history, race, gender, and capital. Discussing his political radicalisation, Sembène often cited working as a labourer on the Marseilles docks in the late 1940s – following a stint at the Paris Citroën factory, after initially stowing away on a ship to France – where he met left-wing unionists, many of them Parti communiste français activists. The anti-colonial Marxist internationalism that so marks the future novelist and filmmaker’s work can also be traced to his membership of the Senegalese Tirailleurs, African soldiers who fought as part of the Free France Army in World War II, many of them (after fighting the Nazis and in multiple cases concentration camp survivors) later mistreated and, in one notorious 1943 incident, mass-murdered at the behest of the white commanders after demanding to be paid their wages in French francs (a story told in the devastating 1988 film Camp de Thiaroye, co-directed by Sembène and Thierno Faty Sow).

Considering such a space’s significance for the filmmaker, it is notable that La Noire de… starts on the Mediterranean docks with a long establishing shot under the credits showing the working waterfront and its large ships, a scene that comes across as both material reality and a kind of theatrical stage or crucial background against which the film’s almost ‘chamber’ version of a trans-continental story will be set. In addition to being the site where the filmmaker came to political maturity, here the fraught, intertwined cultures and economies of Europe and Africa meet – a nexus-point without which colonial history and its ongoing reverberations and renovations would be impossible. While such a border space is marked by gross inequality and exploitation at the macro level, when it comes to real people doing actual work it potentially provides a different kind of intermixing with far more radical outcomes, as Sembène’s own personal story attests.

If the film’s portrayal of the docks and other material spaces, most notably apartments, frequently features a bringing together of material reality, the ideological and the figurative, the latter sometimes takes centre stage but only as first given content by the former. Noticing an African mask hung on the wall of her employers’ living room after Diouana’s arrival in France from the docks, a subsequent flashback shows us her giving it to the new ‘mistress’ as a gift – or we may later wonder, perhaps a warning – after first being hired in Dakar. (When the wife shows her husband the mask with a confused expression, he inspects the gift and says approvingly: “Looks like the real thing”.) By film’s end, the mask has become symbolic of a much larger struggle not just between two women but spanning an entire continent, colonial history, and ongoing economic system. La Noire de…‘s devastating and masterful final sequence will feature this same mask as once more donned by its original Dakar owner, our protagonist’s kid brother – but less now a plaything than an object enabling a new gaze upon colonialism’s ‘liberal’ agent seeking to ‘do the right thing’.

If Sembène’s own politics and investments are never in doubt, La Noire de… avoids easy clichés. The French couple are at first portrayed as relatively friendly in their dealings with Diouana. The husband comes across throughout the film as feckless yet also making occasional comments to his increasingly angry wife that suggest the need to try and understand Diouana’s position. Thanks to the filmmaker’s elliptical approach to the ordering of scenes, we first hear our protagonist complain via voiceover about her mistress shouting at and mistreating her before we have seen any such behaviour take place. This initially risks the viewer thinking the film may have an ‘unreliable narrator’, potentially undermining its political impetus. While the mistress’ interactions with her new maid soon enough match Diouana’s early description, this behaviour mainly post-dates her gradual rebellion by refusing to get out of bed and failing to perform a maid’s duties. Through the wife and husband characters’ differing responses to the unfolding situation, Sembène shows in miniature how colonial and ‘post-colonial’ power structures are sustained with remarkable continuity through different iterations of the same ideology, both explicit and more ‘liberal’ or reluctant.

One of the many striking things about the film is that, despite its very short running time we see extensive scenes of work, here traditionally gendered domestic labour – a subject that narrative cinema, especially in the West, often strikingly avoids. Throughout La Noire de… are peppered scenes showing Diouana engaged in the sheer drudgery and claustrophobic nature of such work, but with a catch. This reluctant maid wears very glamorous clothes and heels. Initially a curious, unexplained fact, the wife becomes increasingly annoyed at such inappropriate attire (“You’re not going to a party”, and “remember, you’re a maid”, she tells her maid), and we gradually realise that – consciously or otherwise – this is part of the young woman’s protean, gradual rebellion from the start. It also suggests, along with later snippets of voice-over and flashback dialogue, that far from a firebrand revolutionary, the glamorous-looking Diouana appears to have been initially rather seduced by the idea of consumerist France and longs to see the fashionable boutiques initially described by her employer. The film is in part about how someone not especially political can become radicalised when material reality so sharply undermines received myth and ideology.

Another effect of La Noire de…’s elliptical ordering of scenes is felt with the Dakar flashbacks, bringing about some generative confusion between France and Senegal through the presence of similar architecture. Colonial reality is both alive in the former colony and in the motherland as represented by the best synecdoche for atomisation: anonymous white apartment complexes. Expressing initial frustration in voiceover that having assumed her job was to look after the couple’s children in France she has instead become a cleaning woman, Diouana describes the atomised reality of Western lifestyle and culture, noting how everyone is shut away in box-like dwellings with “the doors always shut”. If atomisation has often been a familiar theme for left-wing Western discourse, here it is seen and evoked with truly fresh eyes. And this reality is portrayed as in nobody’s interests. When the husband announces he’s going for a nap after lunch with friends, the basic vacuousness and ennui of the couple’s lives becomes apparent when the wife cries out: “Of course you are!”, before complaining: “I’m sick of this life”. In the following voice-over, Diouana then comments: “She wasn’t like that in Dakar. Nor was he.” In the film’s final minutes, the husband suggests that they return to Senegal, with the implication that things will be better back in the former colony.

The lunch scene, an event for which the wife has advertised Diouana as providing “authentic African cooking” (subsequently admired by the visitors, despite being “very spicy”), is the film’s most over-set piece. Complaining via voiceover as she sits alone in the kitchen that “they eat like pigs and jabber away”, Diouana is even more affronted when an older male guest says: “I’ve never kissed a black woman” and proceeds to take the liberty of doing so as she serves the food. By way of an explanation for her apparent disquiet and return to the kitchen, we hear from the dining room: “Their independence has made them less natural.” If the white characters suggests that Africans are more relaxed in their home country, it seems that the French are somewhat the other way around, as if they don’t truly exist out of their overtly colonial (no matter its official ‘post-prefix) context.

In the lunch scene and throughout, the film evokes the relationship between powerful and subaltern colonial subjects (or nations) becoming mutually, regressively co-dependant. In the process, we see play out the psychopathology of colonialism, the retarding impact on both parties. Sembène also thereby emphasises a theme that goes right back to Hegel’s famous notion of the master-slave dialectic radically adapted by Marx, and later writers such as Edward Said and Gayatri Spivak: While the violence, economic exploitation and personal suffering is experienced by the ‘other’, the (European, colonial) ‘subject’ is in another sense the truly imprisoned party because desperately in need of the relationship’s continuation so that a very sense of self – or its illusion – can be sustained. Without it, these people are nothing, with no home to return to. The film makes this clear at every turn, most powerfully of all in its concurrently devastating, radically foreboding yet somehow hopeful final scene, emphasising that such one-way desire has inevitable and potentially world-shaking consequences.

The last piece of the film’s political puzzle emerges with the late arrival of money as a visual motif driving La Noire de…’s final movement: An image just as resonant and important as the mask, together making up the twin – ultimately fused – rails of Sembène’s critique: colonialism and capitalism. Following the two women’s circular tussle over the mask by way of striking cuts between point-of-view shots, the husband seeks to pay Diouana for what may be the first time after his wife retreats. The complex and intuitive nature of this one-woman revolution is then performed in miniature, first falling to her feet upon the appearance of the bank notes (prompting the husband to call his wife so she may witness this reaction, before they return to the living room) and almost immediately giving it back, thereby rejecting a radically unequal business arrangement. This theme of money’s white offer and black refusal – no matter how deserved it might be as payment for work done – achieves a whole new level of pathos and political significance in the film’s masterful final minutes, featuring the return of Sembène himself in the role of Diouana’s school-teacher older brother. The filmmaker’s very brief look to camera after their mother’s refusing the husband’s offer of money is powerful indeed.

Both the debut film of a consistently brilliant career and central tenet in world cinema’s first and most radical chapter,La Noire de… exemplifies perfect political cinema: Forceful, direct, polemical, but never simple, overly didactic, or prosaic, featuring a formal approach and aesthetic style seamlessly matched to its purpose, eschewing representational transparency while insistently showing and analysing a precise material reality. Tied at number 95 in the 2022 BFI Sight and Sound international critics’ poll, Sembène’s first feature – like those of most great filmmakers – is not his best work (I would nominate Xala, Camp de Thiaroye, or his final film, 2004’s Moolaadé). That it snuck into the BFI’s top 100 reflects La Noire de…’s historical importance and obvious quality, while also reflecting the commercial vagaries of film restoration and digital distribution. (More particularly, the undue canon ‘gatekeeper’ influence enjoyed by The Criterion Collection, having recently released the film on Blu-ray/DVD and which pays highly belated and limited attention even to world cinema’s core heritage.) A terse, succinct masterpiece,La Noire de… provides an entrée for even greater things to come, which together comprise one of the great, radical, and for many film-lovers still undiscovered glories of cinema history when taken in its proper sense: as encompassing filmmaking across the world.

The on-paper flaw of its French soundtrack ultimately gives La Noire de… a generative, reflexive touch, a kind of ‘scar’ marking the material and thereby also ideological reality of an African director making a film part-set in Africa. Offering in the process a basic point of political economy and how the market operates by way of a gravitational pull born of colonial history and its ongoing impacts (while this film was made half a decade into Senegal’s official independence, Sembène would later mount a merciless satirical attack on the postcolonial regime’s subservience of France and the capitalist West in his 1975 black comedy, Xala), the frequently glaring inappropriateness of its dubbed French-language soundtrack works to further problematise any ‘realist’ aesthetics that may be assumed in light of the director’s training and politics. To make the effect even more striking, not only is Diouana’s voice dubbed (by Haitian singer Toto Bissainthe) but so are those of the actors playing her French employers. This linguistic aspect only reinforces the film’s other stylistic elements to suggest a presentational, elliptical, and loose modernist sensibility rather than a more representational or realist one.

The original French title of the film, La noire de… refers to a subject as owned or bought by somebody, making clear in three words and suggestive ellipses that this film is about fundamental connections between colonial history, race, gender, and capital. Discussing his political radicalisation, Sembène often cited working as a labourer on the Marseilles docks in the late 1940s – following a stint at the Paris Citroën factory, after initially stowing away on a ship to France – where he met left-wing unionists, many of them Parti communiste français activists. The anti-colonial Marxist internationalism that so marks the future novelist and filmmaker’s work can also be traced to his membership of the Senegalese Tirailleurs, African soldiers who fought as part of the Free France Army in World War II, many of them (after fighting the Nazis and in multiple cases concentration camp survivors) later mistreated and, in one notorious 1943 incident, mass-murdered at the behest of the white commanders after demanding to be paid their wages in French francs (a story told in the devastating 1988 film Camp de Thiaroye, co-directed by Sembène and Thierno Faty Sow).

Considering such a space’s significance for the filmmaker, it is notable that La Noire de… starts on the Mediterranean docks with a long establishing shot under the credits showing the working waterfront and its large ships, a scene that comes across as both material reality and a kind of theatrical stage or crucial background against which the film’s almost ‘chamber’ version of a trans-continental story will be set. In addition to being the site where the filmmaker came to political maturity, here the fraught, intertwined cultures and economies of Europe and Africa meet – a nexus-point without which colonial history and its ongoing reverberations and renovations would be impossible. While such a border space is marked by gross inequality and exploitation at the macro level, when it comes to real people doing actual work it potentially provides a different kind of intermixing with far more radical outcomes, as Sembène’s own personal story attests.

If the film’s portrayal of the docks and other material spaces, most notably apartments, frequently features a bringing together of material reality, the ideological and the figurative, the latter sometimes takes centre stage but only as first given content by the former. Noticing an African mask hung on the wall of her employers’ living room after Diouana’s arrival in France from the docks, a subsequent flashback shows us her giving it to the new ‘mistress’ as a gift – or we may later wonder, perhaps a warning – after first being hired in Dakar. (When the wife shows her husband the mask with a confused expression, he inspects the gift and says approvingly: “Looks like the real thing”.) By film’s end, the mask has become symbolic of a much larger struggle not just between two women but spanning an entire continent, colonial history, and ongoing economic system. La Noire de…‘s devastating and masterful final sequence will feature this same mask as once more donned by its original Dakar owner, our protagonist’s kid brother – but less now a plaything than an object enabling a new gaze upon colonialism’s ‘liberal’ agent seeking to ‘do the right thing’.

If Sembène’s own politics and investments are never in doubt, La Noire de… avoids easy clichés. The French couple are at first portrayed as relatively friendly in their dealings with Diouana. The husband comes across throughout the film as feckless yet also making occasional comments to his increasingly angry wife that suggest the need to try and understand Diouana’s position. Thanks to the filmmaker’s elliptical approach to the ordering of scenes, we first hear our protagonist complain via voiceover about her mistress shouting at and mistreating her before we have seen any such behaviour take place. This initially risks the viewer thinking the film may have an ‘unreliable narrator’, potentially undermining its political impetus. While the mistress’ interactions with her new maid soon enough match Diouana’s early description, this behaviour mainly post-dates her gradual rebellion by refusing to get out of bed and failing to perform a maid’s duties. Through the wife and husband characters’ differing responses to the unfolding situation, Sembène shows in miniature how colonial and ‘post-colonial’ power structures are sustained with remarkable continuity through different iterations of the same ideology, both explicit and more ‘liberal’ or reluctant.

One of the many striking things about the film is that, despite its very short running time we see extensive scenes of work, here traditionally gendered domestic labour – a subject that narrative cinema, especially in the West, often strikingly avoids. Throughout La Noire de… are peppered scenes showing Diouana engaged in the sheer drudgery and claustrophobic nature of such work, but with a catch. This reluctant maid wears very glamorous clothes and heels. Initially a curious, unexplained fact, the wife becomes increasingly annoyed at such inappropriate attire (“You’re not going to a party”, and “remember, you’re a maid”, she tells her maid), and we gradually realise that – consciously or otherwise – this is part of the young woman’s protean, gradual rebellion from the start. It also suggests, along with later snippets of voice-over and flashback dialogue, that far from a firebrand revolutionary, the glamorous-looking Diouana appears to have been initially rather seduced by the idea of consumerist France and longs to see the fashionable boutiques initially described by her employer. The film is in part about how someone not especially political can become radicalised when material reality so sharply undermines received myth and ideology.

Another effect of La Noire de…’s elliptical ordering of scenes is felt with the Dakar flashbacks, bringing about some generative confusion between France and Senegal through the presence of similar architecture. Colonial reality is both alive in the former colony and in the motherland as represented by the best synecdoche for atomisation: anonymous white apartment complexes. Expressing initial frustration in voiceover that having assumed her job was to look after the couple’s children in France she has instead become a cleaning woman, Diouana describes the atomised reality of Western lifestyle and culture, noting how everyone is shut away in box-like dwellings with “the doors always shut”. If atomisation has often been a familiar theme for left-wing Western discourse, here it is seen and evoked with truly fresh eyes. And this reality is portrayed as in nobody’s interests. When the husband announces he’s going for a nap after lunch with friends, the basic vacuousness and ennui of the couple’s lives becomes apparent when the wife cries out: “Of course you are!”, before complaining: “I’m sick of this life”. In the following voice-over, Diouana then comments: “She wasn’t like that in Dakar. Nor was he.” In the film’s final minutes, the husband suggests that they return to Senegal, with the implication that things will be better back in the former colony.

The lunch scene, an event for which the wife has advertised Diouana as providing “authentic African cooking” (subsequently admired by the visitors, despite being “very spicy”), is the film’s most over-set piece. Complaining via voiceover as she sits alone in the kitchen that “they eat like pigs and jabber away”, Diouana is even more affronted when an older male guest says: “I’ve never kissed a black woman” and proceeds to take the liberty of doing so as she serves the food. By way of an explanation for her apparent disquiet and return to the kitchen, we hear from the dining room: “Their independence has made them less natural.” If the white characters suggests that Africans are more relaxed in their home country, it seems that the French are somewhat the other way around, as if they don’t truly exist out of their overtly colonial (no matter its official ‘post-prefix) context.

In the lunch scene and throughout, the film evokes the relationship between powerful and subaltern colonial subjects (or nations) becoming mutually, regressively co-dependant. In the process, we see play out the psychopathology of colonialism, the retarding impact on both parties. Sembène also thereby emphasises a theme that goes right back to Hegel’s famous notion of the master-slave dialectic radically adapted by Marx, and later writers such as Edward Said and Gayatri Spivak: While the violence, economic exploitation and personal suffering is experienced by the ‘other’, the (European, colonial) ‘subject’ is in another sense the truly imprisoned party because desperately in need of the relationship’s continuation so that a very sense of self – or its illusion – can be sustained. Without it, these people are nothing, with no home to return to. The film makes this clear at every turn, most powerfully of all in its concurrently devastating, radically foreboding yet somehow hopeful final scene, emphasising that such one-way desire has inevitable and potentially world-shaking consequences.

The last piece of the film’s political puzzle emerges with the late arrival of money as a visual motif driving La Noire de…’s final movement: An image just as resonant and important as the mask, together making up the twin – ultimately fused – rails of Sembène’s critique: colonialism and capitalism. Following the two women’s circular tussle over the mask by way of striking cuts between point-of-view shots, the husband seeks to pay Diouana for what may be the first time after his wife retreats. The complex and intuitive nature of this one-woman revolution is then performed in miniature, first falling to her feet upon the appearance of the bank notes (prompting the husband to call his wife so she may witness this reaction, before they return to the living room) and almost immediately giving it back, thereby rejecting a radically unequal business arrangement. This theme of money’s white offer and black refusal – no matter how deserved it might be as payment for work done – achieves a whole new level of pathos and political significance in the film’s masterful final minutes, featuring the return of Sembène himself in the role of Diouana’s school-teacher older brother. The filmmaker’s very brief look to camera after their mother’s refusing the husband’s offer of money is powerful indeed.

Both the debut film of a consistently brilliant career and central tenet in world cinema’s first and most radical chapter,La Noire de… exemplifies perfect political cinema: Forceful, direct, polemical, but never simple, overly didactic, or prosaic, featuring a formal approach and aesthetic style seamlessly matched to its purpose, eschewing representational transparency while insistently showing and analysing a precise material reality. Tied at number 95 in the 2022 BFI Sight and Sound international critics’ poll, Sembène’s first feature – like those of most great filmmakers – is not his best work (I would nominate Xala, Camp de Thiaroye, or his final film, 2004’s Moolaadé). That it snuck into the BFI’s top 100 reflects La Noire de…’s historical importance and obvious quality, while also reflecting the commercial vagaries of film restoration and digital distribution. (More particularly, the undue canon ‘gatekeeper’ influence enjoyed by The Criterion Collection, having recently released the film on Blu-ray/DVD and which pays highly belated and limited attention even to world cinema’s core heritage.) A terse, succinct masterpiece,La Noire de… provides an entrée for even greater things to come, which together comprise one of the great, radical, and for many film-lovers still undiscovered glories of cinema history when taken in its proper sense: as encompassing filmmaking across the world.

Borom Sarret (1963)

With Borom Sarret – ‘The Wagoner’ in English – Ousmane Sembène sets

out many of the key themes that will mark his major work, highlighting the

inherent inequalities of colonialism’s heritage and modern capitalism, enunciated

via a style that carefully avoids representational claims to realism.

Predicting La Noire de, this 19-minute film’s

dialogue is presented in voice-over from the start. Notably, it is Sembène’s own

voice we hear articulating thoughts and observations attributed to his protagonist,

the titular wagoner, but that take on a dimension later in the film more

suggestive of the author himself as literally announcing his core concerns directly

to the viewer.

The main character’s lips, it turns out, never move throughout the film. And when secondary figures speak, the words we hear on the soundtrack do not match the movements of their mouths (where it can be detected), Sembène making no effort to mask the dubbing and instead emphasising it as central plank of his deliberate, reflexive strategy. This highlighting of dubbed sound already in train from the first scene (when we hear his wife offer him luck for the day, her mouth remains closed), upon the arrival of an aerial shot of their Dakar neighbourhood the effect is of a carefully demarcated and framed space or ‘set’ rendered via a self-consciously heightened camera position. This approach to would-be establishing shots will recur at the very start of La Noire de… and as key moments punctuating later Sembène films right up to his final masterpiece, Moolaadé, providing for a ‘presentational’ effect.

As with La Noire de..., Sembène doesn’t strain to initially offer us especially reliable, likeable, or sympathetic characters. Here his protagonist comes across as irritable and rather self-pitying from the start (and one suspects, a little hopeless), likens crippled beggars to flies, and complains about a pregnant client putting her head on his shoulder while resting on the way to hospital (and tells the viewer: “These modern women! Impossible to understand”). When he reluctantly takes a fare going uptown after first telling the suited client that wagoners are not allowed there due presumably to their ‘backward’ appearance in a space dominated by nice cars and sleek architecture, the film cuts to the same environment seen extensively in La Noire de… in both its French and Dakar scenes, dominated by white apartment blocks and here accompanied by light classical music. This is a film about stark demarcations of different yet connected spaces, classes, worlds.

After the wagoner is ripped off by his uptown client while being interrogated by a security guard – a fear motivating his initial refusal of the job – Sembène voices the following lament on the soundtrack: “That guy said he had contacts. Thieves, most likely. Who: Who can we trust? It’s the same everywhere in the world. They know how to read, and they know how to lie. … Yesterday it was the same thing. The day before, too. … This jail. This is modern life. This is life in this country.“ As we hear these lines, the camera shows rows of impersonal, matching apartment building windows while the wagoner/Sembène homes in on the very issue of space and radically unequal development, but also – a theme taken up with some real penetration in La Noire de… –the void at the heart of such fundamentally unequal modern life itself: “These houses… That’s it. These houses.”

The film ends with the defeated wagoner returning home upon which his wife hands him their baby and leaves the house to seek food, without complaint. Prefacing his many feature films with female protagonists, Borom Serrat’s final scene thereby strongly suggests a theme Sembène emphasised in multiple interviews. Men having effectively failed, or too much the agents of ongoing regression, any future hope of improvement, let alone revolutionary change, lies with women. Exactly how the wagoner’s wife will procure money for food, the personal cost and risks she and other women pay every day to enable their own survival and often that of their families, let alone becoming potential agents of revolutionary change, is and remains a lingering question.

The main character’s lips, it turns out, never move throughout the film. And when secondary figures speak, the words we hear on the soundtrack do not match the movements of their mouths (where it can be detected), Sembène making no effort to mask the dubbing and instead emphasising it as central plank of his deliberate, reflexive strategy. This highlighting of dubbed sound already in train from the first scene (when we hear his wife offer him luck for the day, her mouth remains closed), upon the arrival of an aerial shot of their Dakar neighbourhood the effect is of a carefully demarcated and framed space or ‘set’ rendered via a self-consciously heightened camera position. This approach to would-be establishing shots will recur at the very start of La Noire de… and as key moments punctuating later Sembène films right up to his final masterpiece, Moolaadé, providing for a ‘presentational’ effect.

As with La Noire de..., Sembène doesn’t strain to initially offer us especially reliable, likeable, or sympathetic characters. Here his protagonist comes across as irritable and rather self-pitying from the start (and one suspects, a little hopeless), likens crippled beggars to flies, and complains about a pregnant client putting her head on his shoulder while resting on the way to hospital (and tells the viewer: “These modern women! Impossible to understand”). When he reluctantly takes a fare going uptown after first telling the suited client that wagoners are not allowed there due presumably to their ‘backward’ appearance in a space dominated by nice cars and sleek architecture, the film cuts to the same environment seen extensively in La Noire de… in both its French and Dakar scenes, dominated by white apartment blocks and here accompanied by light classical music. This is a film about stark demarcations of different yet connected spaces, classes, worlds.

After the wagoner is ripped off by his uptown client while being interrogated by a security guard – a fear motivating his initial refusal of the job – Sembène voices the following lament on the soundtrack: “That guy said he had contacts. Thieves, most likely. Who: Who can we trust? It’s the same everywhere in the world. They know how to read, and they know how to lie. … Yesterday it was the same thing. The day before, too. … This jail. This is modern life. This is life in this country.“ As we hear these lines, the camera shows rows of impersonal, matching apartment building windows while the wagoner/Sembène homes in on the very issue of space and radically unequal development, but also – a theme taken up with some real penetration in La Noire de… –the void at the heart of such fundamentally unequal modern life itself: “These houses… That’s it. These houses.”

The film ends with the defeated wagoner returning home upon which his wife hands him their baby and leaves the house to seek food, without complaint. Prefacing his many feature films with female protagonists, Borom Serrat’s final scene thereby strongly suggests a theme Sembène emphasised in multiple interviews. Men having effectively failed, or too much the agents of ongoing regression, any future hope of improvement, let alone revolutionary change, lies with women. Exactly how the wagoner’s wife will procure money for food, the personal cost and risks she and other women pay every day to enable their own survival and often that of their families, let alone becoming potential agents of revolutionary change, is and remains a lingering question.

Djibril Diop Mambety

Mambéty (1945, Senegal − 1998, France) was a Senegalese filmmaker, actor, orator composer and poet. Despite his small oeuvre, he holds a legendary status withi African Cinema. Besides being trained as an actor at the National Daniel Aoran Theatre in Dakar, he had no formal training in filmmaking. In 1969, at age 23, Mambéty directed and produced

his first short film, Contras’ City (City of Contrasts). The following year Mambéty

made another short, Badou Boy, which won the Silver Tanit award at the 197 Carthage Film Festival in Tunisia.

his first short film, Contras’ City (City of Contrasts). The following year Mambéty

made another short, Badou Boy, which won the Silver Tanit award at the 197 Carthage Film Festival in Tunisia.

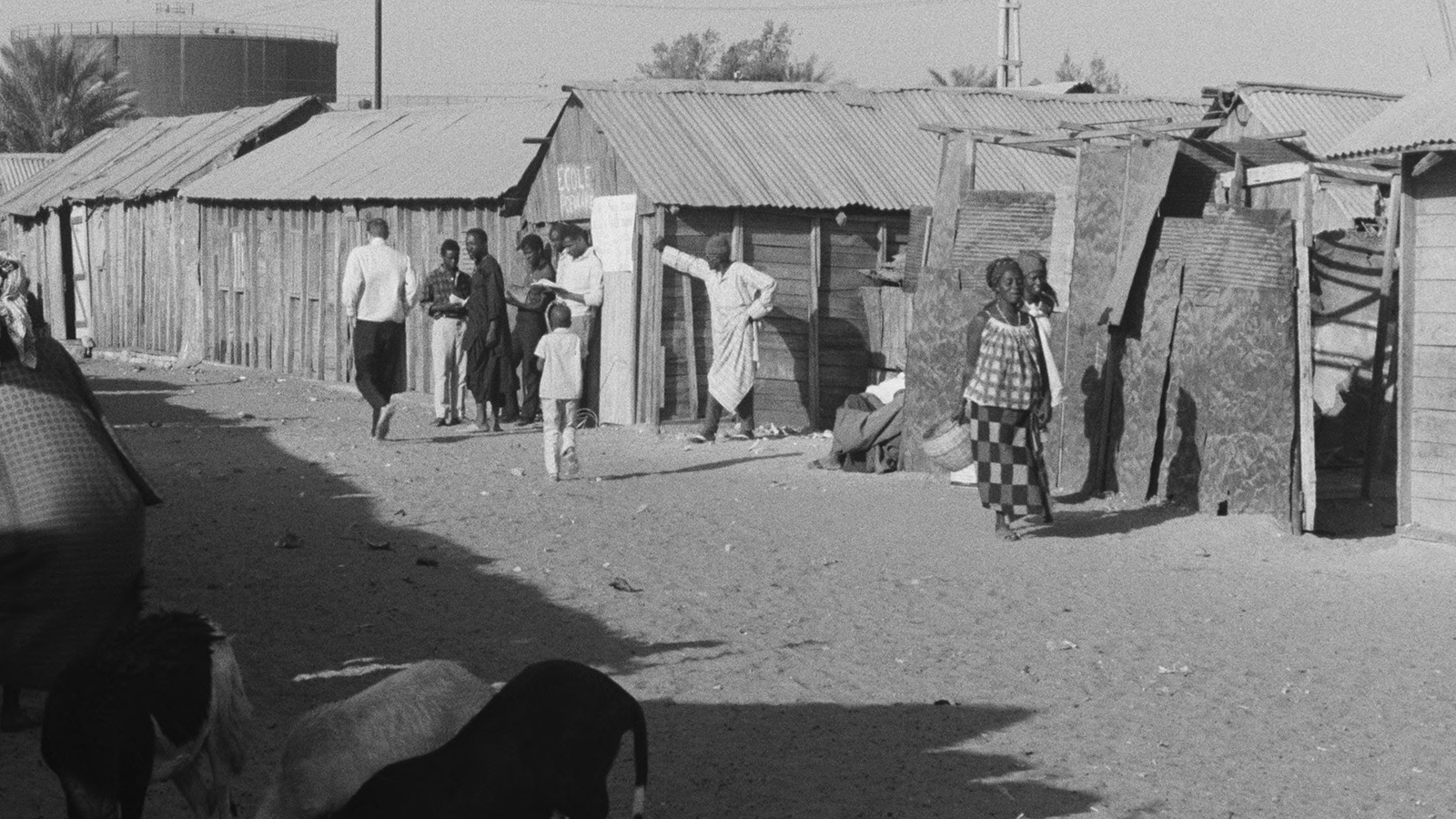

Contras City (1969)

A fictional documentary that portrays the city of Dakar, Senegal, as we hear th conversation between a Senegalese man (the director, Djibril Diop Mambéty) an a French woman, Inge Hirschnitz. As we travel through the city in a picturesqu horse-drawn wagon, we chaotically rush into this and that popular neighborhood of the capital, discovering contrast after

contrast: A small African community waiting at the Church’s door, Muslim praying on the sidewalk, the Rococo architecture of the Government buildings, the modest stores of the

craftsmen near the main market.

contrast: A small African community waiting at the Church’s door, Muslim praying on the sidewalk, the Rococo architecture of the Government buildings, the modest stores of the

craftsmen near the main market.

The Restorations

Black

Girl was

restored by Cineteca di Bologna/ L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in

association with the Sembène Estate, Institut National de

l’Audiovisuel, INA, Eclair laboratories and the Centre National de

Cinématographie. Restoration funded by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema

Project. The restoration of La Noire

de… was made possible through the use of the original camera and

sound negative provided by INA and the Sembène Estate and preserved at the

CNC – Archives Françaises du Film. A vintage print preserved at the

Cinémathèque Française was used as reference.

Borom Sarret was restored by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory and Laboratoires Éclair, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Institut National de l’Audiovisuel, and the Sembène Estate. Restoration funded by Doha Film Institute. The restoration of was made possible through the use of the original camera and sound negatives provided by INA and preserved at Éclair Laboratories.

Contras City was restored in 2020 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata an The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project in association with The Criterio Collection. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. This restoration is part of the African Film Heritage Project, an initiative created by The Film Foundation’ World Cinema Project, the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers and UNESCO– in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna – to help locate, restore, and disseminate African cinema. The 4K restoration of Contras’ City was made from the inter-negative as well as the original sound negative provided by Teemour Mambéty and preserve at LTC Patrimoine. A vintage print of the film was used as reference for color grading.

Borom Sarret was restored by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory and Laboratoires Éclair, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Institut National de l’Audiovisuel, and the Sembène Estate. Restoration funded by Doha Film Institute. The restoration of was made possible through the use of the original camera and sound negatives provided by INA and preserved at Éclair Laboratories.

Contras City was restored in 2020 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata an The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project in association with The Criterio Collection. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. This restoration is part of the African Film Heritage Project, an initiative created by The Film Foundation’ World Cinema Project, the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers and UNESCO– in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna – to help locate, restore, and disseminate African cinema. The 4K restoration of Contras’ City was made from the inter-negative as well as the original sound negative provided by Teemour Mambéty and preserve at LTC Patrimoine. A vintage print of the film was used as reference for color grading.

Credits

Black Girl

La noire de… | Director: Ousmane SEMBÈNE | Senegal, France | 1966 | 55 mins. | 2K Flat DCP (orig. 35mm, 1.37:1) | B&W | Mono Sd. | French, Wolof with Eng. subtitles | U/C15+.

Production Companies: Filmi Doomireew, Actualités Françaises | Producer: André ZWOBADA | Script: Ousmane SEMBÈNE, from his short story La noire de… | Photography: Christian LACOSTE | Editor: André GAUDIER.

Cast: N'bissine Thérèse DIOP (‘Diouana; dubbed by Toto BISSAINTHE), Anne-Marie JELINEK (‘Madame’; dubbed by Sophie LECLERC), Robert FONTAINE (‘Monsieur’; dubbed by Robert MACEY), Momar Nar SENE (‘The Young Man’), Toto BISSAINTHE (Narrator).

Borom Sarret

Le charretier, The Wagoner | Director: Ousmane SEMBÈNE | Senegal, France | 1963 | 18 mins. | 2K Flat DCP (orig. 35mm, 1.37:1) | B&W | Mono Sd. | French, Wolof with Eng. subtitles | U/C15+.

Production Companies: Filmi Doomireew, Actualités Françaises | Producer: Ousmane SEMBÈNE | Script: Ousmane SEMBÈNE | Photography: Christian LACOSTE | Editor: André GAUDIER.

Cast: Ly ABDOULAY (‘The Wagonier’), ALBOURAH (‘The Wife’).

Contras City

Director/Script. Djibril Diop MAMBÉTY | Production Company: Studio Kankourama Director of Photography: Georges BRACHER |Editors: Jean-Bernard BONIS, Marino

RIO // Cast: Djibril Diop MAMBÉTY; Inge HIRSCHNIT Senegal | 1968 | 18 mins. | 2K Flat DCP (orig. 35mm, 1.37:1) | B&W | Mono Sd. | Wolof withEng. subtitles | U/C15+

La noire de… | Director: Ousmane SEMBÈNE | Senegal, France | 1966 | 55 mins. | 2K Flat DCP (orig. 35mm, 1.37:1) | B&W | Mono Sd. | French, Wolof with Eng. subtitles | U/C15+.

Production Companies: Filmi Doomireew, Actualités Françaises | Producer: André ZWOBADA | Script: Ousmane SEMBÈNE, from his short story La noire de… | Photography: Christian LACOSTE | Editor: André GAUDIER.

Cast: N'bissine Thérèse DIOP (‘Diouana; dubbed by Toto BISSAINTHE), Anne-Marie JELINEK (‘Madame’; dubbed by Sophie LECLERC), Robert FONTAINE (‘Monsieur’; dubbed by Robert MACEY), Momar Nar SENE (‘The Young Man’), Toto BISSAINTHE (Narrator).

Borom Sarret

Le charretier, The Wagoner | Director: Ousmane SEMBÈNE | Senegal, France | 1963 | 18 mins. | 2K Flat DCP (orig. 35mm, 1.37:1) | B&W | Mono Sd. | French, Wolof with Eng. subtitles | U/C15+.

Production Companies: Filmi Doomireew, Actualités Françaises | Producer: Ousmane SEMBÈNE | Script: Ousmane SEMBÈNE | Photography: Christian LACOSTE | Editor: André GAUDIER.

Cast: Ly ABDOULAY (‘The Wagonier’), ALBOURAH (‘The Wife’).

Contras City

Director/Script. Djibril Diop MAMBÉTY | Production Company: Studio Kankourama Director of Photography: Georges BRACHER |Editors: Jean-Bernard BONIS, Marino

RIO // Cast: Djibril Diop MAMBÉTY; Inge HIRSCHNIT Senegal | 1968 | 18 mins. | 2K Flat DCP (orig. 35mm, 1.37:1) | B&W | Mono Sd. | Wolof withEng. subtitles | U/C15+