BATCH 81 (1982)

8:30 PM, Thursday April 28

Introduced by Quentin Turnour

Randwick Ritz

Director: Mike De Leon

Country: Philippines

Year: 1982

Runtime: 100 minutes

Rating: UC15+

Language: Tagalog, Filipino/ English subtitles

TICKETS ⟶

“A MARVEL OF A FILM, A MASTERPIECE OF PHILLIPINE CINEMA” – TIMOTHY ONG

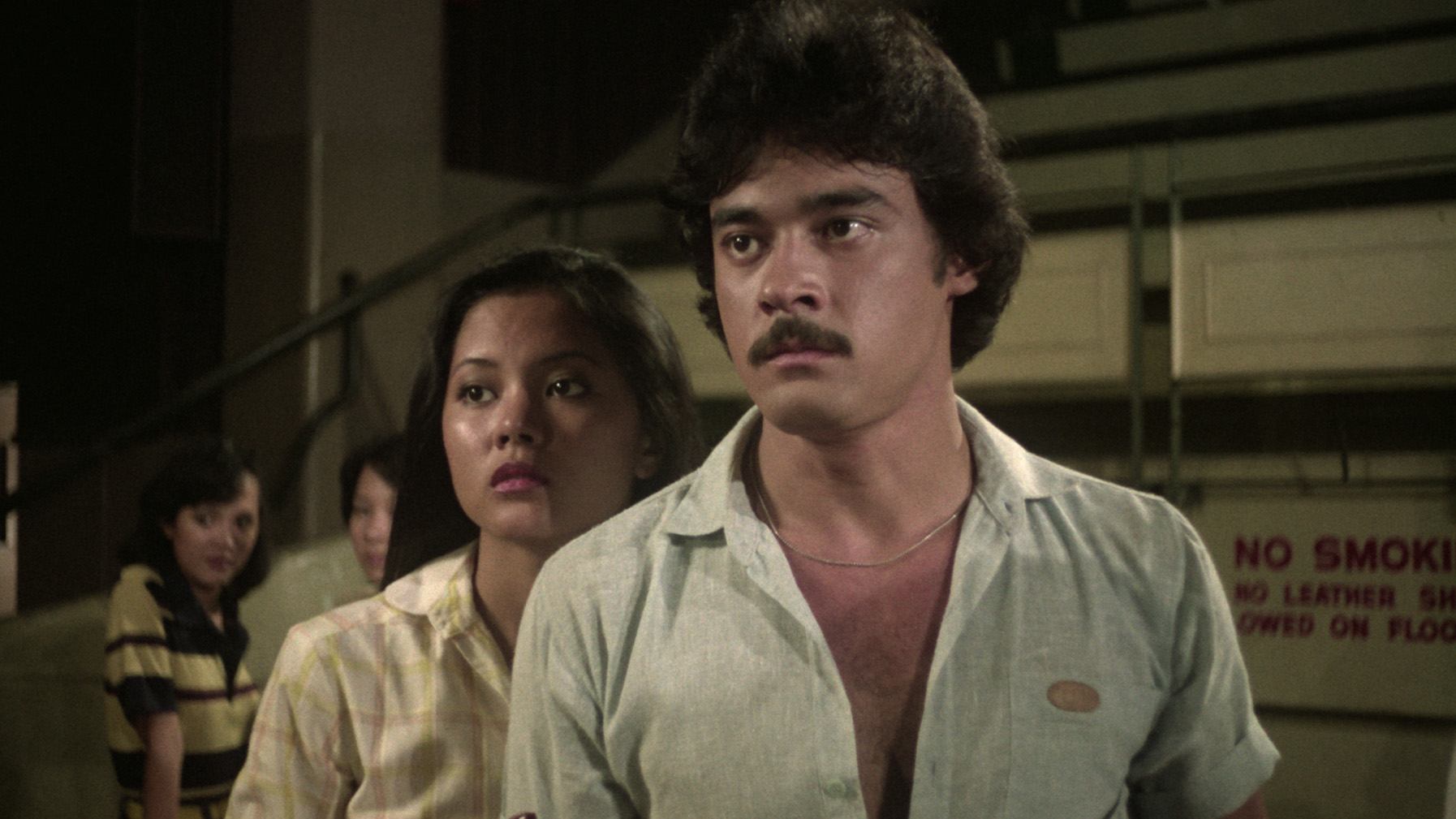

Often described as a Philippines’ Clockwork Orange, Mike De Leon’s drama, set in an unnamed university follows new student Sid Lucero through his initiation into the Alpha Kappa Omega fraternity.

The “hazing” initiations take place over six months and become increasingly sadistic and humiliating. The totalitarian - even fascistic - metaphor is impossible to miss as the progressive loss of individual liberty starts to mirror the oppressive martial law of the Marcos regime.

“Rich with symbolism…the chanting alone resembles a fascist anthem and echoes the New Society theme of the Marcos dictatorship, which was four years away from its downfall when this film was released”.

– Ricky Torre

Watch the Trailer

Introduced by Quentin Turnour, Film Archivist, Curator, Cinema Reborn programming consultant and Project Officer at the Audiovisual Preservation Section of the National Archives of Australia.

FILM NOTES

Two or Three Things I Know About Mike de Leon

By Tony Rayns

By Tony Rayns

He has competition from a few dead

masters – Gerardo de Leon, Lino Brocka, Mario O’Hara and Ishmael Bernal head

the list – but I suspect Mike De Leon is the foremost of all Filipino

filmmakers. He’s an intensely private man: he has always shied away from

interviews and self-promotion, but at the time of writing he is putting the

finishing touches to an autobiographical scrapbook called Last Look Back. It may be out by the time you read this. He

invited me to write the preface for it, so I had the chance to read an early

draft of the text. He frames it as mini-essays or commentaries on a series of

evocative photos, film stills and other images. I learned a lot from his draft

text.

Of course, I already knew the basic biography. He was born in 1947, read humanities at the Ateneo de Manila, studied art history at the University of Heidelberg and got involved with cinema only when he returned to the Philippines. But he came from a filmmaking family: his grandmother Narcisa (known as Doña Sisang) had founded the major studio LVN in 1938, and his father Manuel ran the company until it ended regular production in 1961. LVN continued as a facilities house for other producers, and Mike took over running it in 1970, devoting his attention to its processing lab from 1972. In 1975 he founded the company Cinema Artists, made his experimental short Monologue, and produced and photographed Brocka’s Manila, in the Claws of Light. He directed his debut feature The Rites of May (Itim, literally ‘Black’) the following year. Since then, sometimes with long gaps between films, he has made eight more features (one shot on video for TV), plus an episode for a portmanteau film; he also photographed Eddie Romero’s epic Aguila(1980) and took a steering role in the agit-prop short Omens (Signos, 1984), made to protest the assassination of Benigno Aquino, signed by eight members of the Concerned Artists group. He has very recently released the tiny short Babuyan (2021), which shows that he would like his great 1981 feature about coercive control Kisapmata to be read politically, and warns that cronies of the late corrupt dictator Marcos are staging their come-back.

The bare facts tell little of the real story. The first thing to note is that he came into filmmaking with no grounding in – and little interest in – the traditional, generic Filipino film culture. An interest in European art cinema picked up during his time in Germany, combined with an innate technical perfectionism, gave him an ‘outsider’ perspective on film language and visual style. From the start, his films didn’t follow the ‘rules’ of Pinoy melodrama: his storytelling and sense of micro and macro structures were different. Even on the two occasions he tried for commercial success with romantic melodramas, in 1977 and 1985, his emphases were unusual. He has never been a ‘mainstream’ director in Filipino film culture.

Second, his impulse to attack the ruthless and immoral patriarchy was already obvious in his debut feature, but it took him a few years to acknowledge that these attacks were fundamentally political. Kisapmata and Batch ’81, made in rapid succession in 1981/82 and screened side by side in the Directors Fortnight in Cannes, both identified the patriarchy as essentially fascistic. Two subsequent collaborations with the left-wing writer Jose ‘Pete’ Lacaba – on Omensand the feature Sister Stella L – confirmed a newly political orientation, pointing towards the popular uprising that overthrew Marcos. His latest feature Citizen Jake (2019; I’d say his masterpiece) continues this line of attack while reflecting ruefully on the compromises and limitations of politicised art.

Third, he has become the Philippines’ answer to Martin Scorsese in his latter-day dedication to film preservation and restoration. He started down this road when he supervised the restoration of Manila, In the Claws of Light for Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation, published on Blu-ray by Criterion in the US and the BFI in Britain. He’s been vocally critical of the failure to preserve the LVN back-catalogue, much of which is lost, and he took a very active role in restoring and rereleasing his late father’s prestige production of Nick Joaquin’s Portrait of the Artist as Filipino (1965, directed by Lamberto Avellana). In the last few years, while battling health issues, he has supervised restorations and new hi-res scans of his own key works. They will be published on Blu-ray by Carlotta Films in Paris during 2022, and it seems safe to assume that discriminating labels in the English-speaking world will follow suit.

In 2015, Mike De Leon published his first book, a handsome monograph on the restoration of Nick Joaquin’s Portrait of the Artist as Filipino, which doubles as a pictorial history of LVN Pictures. He wrote a foreword for the book, which ends with these words:

“This commemorative book – my first as a publisher – contains images and recollections from half a century ago and brings back many memories of my father and the world he lived in, and the world he brought to the movies. One of those memories is of my father telling me many times before he died: ‘Mike, whatever I leave you, do not spend it making movies.’

Well, he didn’t say anything about making books, or about restoring his movies.”

Since then, the Asian Film Archive in Singapore has published an equally handsome monograph on the restoration of Batch ’81 (like the Portrait book, designed by De Leon’s close collaborator, the late production designer Cesar Hernando), which contains a detailed history of the production, the original script and information about scenes deleted from the final cut. As we noted in our first paragraph, Mike De Leon’s second volume as publisher, Last Look Back, is due out this year.

Of course, I already knew the basic biography. He was born in 1947, read humanities at the Ateneo de Manila, studied art history at the University of Heidelberg and got involved with cinema only when he returned to the Philippines. But he came from a filmmaking family: his grandmother Narcisa (known as Doña Sisang) had founded the major studio LVN in 1938, and his father Manuel ran the company until it ended regular production in 1961. LVN continued as a facilities house for other producers, and Mike took over running it in 1970, devoting his attention to its processing lab from 1972. In 1975 he founded the company Cinema Artists, made his experimental short Monologue, and produced and photographed Brocka’s Manila, in the Claws of Light. He directed his debut feature The Rites of May (Itim, literally ‘Black’) the following year. Since then, sometimes with long gaps between films, he has made eight more features (one shot on video for TV), plus an episode for a portmanteau film; he also photographed Eddie Romero’s epic Aguila(1980) and took a steering role in the agit-prop short Omens (Signos, 1984), made to protest the assassination of Benigno Aquino, signed by eight members of the Concerned Artists group. He has very recently released the tiny short Babuyan (2021), which shows that he would like his great 1981 feature about coercive control Kisapmata to be read politically, and warns that cronies of the late corrupt dictator Marcos are staging their come-back.

The bare facts tell little of the real story. The first thing to note is that he came into filmmaking with no grounding in – and little interest in – the traditional, generic Filipino film culture. An interest in European art cinema picked up during his time in Germany, combined with an innate technical perfectionism, gave him an ‘outsider’ perspective on film language and visual style. From the start, his films didn’t follow the ‘rules’ of Pinoy melodrama: his storytelling and sense of micro and macro structures were different. Even on the two occasions he tried for commercial success with romantic melodramas, in 1977 and 1985, his emphases were unusual. He has never been a ‘mainstream’ director in Filipino film culture.

Second, his impulse to attack the ruthless and immoral patriarchy was already obvious in his debut feature, but it took him a few years to acknowledge that these attacks were fundamentally political. Kisapmata and Batch ’81, made in rapid succession in 1981/82 and screened side by side in the Directors Fortnight in Cannes, both identified the patriarchy as essentially fascistic. Two subsequent collaborations with the left-wing writer Jose ‘Pete’ Lacaba – on Omensand the feature Sister Stella L – confirmed a newly political orientation, pointing towards the popular uprising that overthrew Marcos. His latest feature Citizen Jake (2019; I’d say his masterpiece) continues this line of attack while reflecting ruefully on the compromises and limitations of politicised art.

Third, he has become the Philippines’ answer to Martin Scorsese in his latter-day dedication to film preservation and restoration. He started down this road when he supervised the restoration of Manila, In the Claws of Light for Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation, published on Blu-ray by Criterion in the US and the BFI in Britain. He’s been vocally critical of the failure to preserve the LVN back-catalogue, much of which is lost, and he took a very active role in restoring and rereleasing his late father’s prestige production of Nick Joaquin’s Portrait of the Artist as Filipino (1965, directed by Lamberto Avellana). In the last few years, while battling health issues, he has supervised restorations and new hi-res scans of his own key works. They will be published on Blu-ray by Carlotta Films in Paris during 2022, and it seems safe to assume that discriminating labels in the English-speaking world will follow suit.

In 2015, Mike De Leon published his first book, a handsome monograph on the restoration of Nick Joaquin’s Portrait of the Artist as Filipino, which doubles as a pictorial history of LVN Pictures. He wrote a foreword for the book, which ends with these words:

“This commemorative book – my first as a publisher – contains images and recollections from half a century ago and brings back many memories of my father and the world he lived in, and the world he brought to the movies. One of those memories is of my father telling me many times before he died: ‘Mike, whatever I leave you, do not spend it making movies.’

Well, he didn’t say anything about making books, or about restoring his movies.”

Since then, the Asian Film Archive in Singapore has published an equally handsome monograph on the restoration of Batch ’81 (like the Portrait book, designed by De Leon’s close collaborator, the late production designer Cesar Hernando), which contains a detailed history of the production, the original script and information about scenes deleted from the final cut. As we noted in our first paragraph, Mike De Leon’s second volume as publisher, Last Look Back, is due out this year.

The FilmBy Noel Vera

Call

it his fascist masterpiece. Mike de Leon's Batch

‘81 is an allegorical treatise on the nature of

fascism, specifically that of the Marcos Administration, in a film that makes

its argument (I submit) largely through fascist means.

De Leon's reputation as a control freak is legendary and, to be honest, not entirely unfounded. Here he tells the story of one Sid Lucero, aspiring to enter the frat Alpha Kappa Omega: through Sid's eyes we see the initiation process, through his ears we hear the rules and philosophy of the fraternity, through his thoughts (done in voiceover) we learn of his reaction to the frat's unfolding nature. Oh, Sid spends onscreen time with his fellow pledges, who function as distinct supporting players (strangely the frat masters remain mostly undifferentiated walking ciphers), but it's only Sid's thoughts we hear, only Sid's consciousness that absorbs the film's narrative, even the corollary narratives of his brothers.

De Leon has rarely been shy about his admiration for legendary filmmaker Stanley Kubrick; if anything you can see Kubrick's influence on De Leon's geometrically meticulous visual style, his distant emotional tone, his tendency to subject characters to forces beyond their control. If Kisapmata is De Leon's tribute to Kubrick's The Shining (the former in my opinion being the superior film), Batch '81 would arguably be De Leon's Clockwork Orange, and not merely because of an overt Clockwork-style rock-music number, where a mannequin is eviscerated onscreen: specific events are mirrored (a head dunked in a tank of filthy water; a man strapped to a chair; one film beginning with a gang rumble, the other ending with same), crucial themes echoed ("Anong desisyon mo?" (What's your decision?) recalling Clockwork's onscreen query: "What's it going to be then, eh?"--both films focusing on the primacy and degradation of free will).

If there's a difference between the two I'd say it's one borne of circumstance: Kubrick was a well-funded filmmaker, with a healthy commercial relationship tangential if not completely dependent on mainstream Hollywood. De Leon is not without resources (he is the grandson of film matriarch Narcisa De Leon, of LVN Pictures) but his budgets, if not starvation poor, are modest, and he scales his ambitions accordingly. Where Kubrick's films are elaborately constructed and obsessively detailed mindscapes, the extravagant sets used eccentrically (the vast hotel in The Shining, the unending ship in 2001, the decadent mansions in Paths of Glory, Lolita, Barry Lyndon, and Eyes Wide Shut) De Leon goes the other direction, employing naturalistic environments (a family home, a frat house basement) expressionistically, transforming them into psychic traps where his characters gnaw desperately at each other and at themselves, seeking escape.

Hence the frat house in Batch '81, where much of the action takes place. As designed by longtime De Leon collaborator Cesar Hernando the rooms are claustrophobic spaces where people can scream freely unheard, too small for those confined (seven freshly hatched pledges) to avoid notice, too narrow for them to do anything other than ask "more please!" The rooms eliminate any notion of freedom, any possible lifestyle alternative (a frat-free college career, for one), any thoughts outside of the moment: you are in a world of pain, and endurance of that pain is the sum total meaning of your life (past and future--other than your pending membership--having been beaten out of your skull).

De Leon's cinematography has always been functional almost to the point of unimpressive at least on first viewing, though they do have a crispness of image and precision of effect few other filmmakers, Filipino or otherwise, can touch. For this production De Leon (with cinematographer Rody Lacap) lights the sets with brutal frankness, the sole source of light often apparently being an incandescent bulb or two. Kubrick employs similar lighting in several of his films (the prison stage show in Clockwork; the lunar excavation in 2001), but where Kubrick uses the harsh glare to herald a spectacular revelation--the results of a mind experiment, the climax of an alien civilization's patient manipulations--De Leon employs them for a more quotidian reason: to illuminate the truth without flinching, without evasion. To show physical and psychological violence unadorned.

Need to mention one of De Leon's most important collaborators--don't usually like to discuss acting as I subscribe to Robert Bresson's theory on the subject (no actors, no parts, no staging; being as opposed to seeming) but even I have to admit much of the force of the film is due to the performance of the late great Mark Gil as Sid. If Al Pacino does volatile like no other actor, and Robert De Niro intense interiority, Gil seems to do both well, flipping effortlessly from one (yelling as his friend is being killed before him) to the other (meditating on his batchmates' faithlessness). And where De Niro practiced Method to the point of eating his way to obesity for Raging Bull, I doubt if even he is capable of enduring what Gil endures in one particularly harrowing scene, involving surgical clamps. No CGI, no apparent prosthetics--prosthetics do not gradually turn red onscreen.

Finally, the script, by industry veterans Clodualdo del Mundo, Jr., Raquel Villavicencio, and De Leon himself: a clean, linear storyline that traces Sid's transformation from trembling neophyte to full frat brother. Aphorisms (presumably recorded by the writers from actual frat language) are constantly flung about during the rituals: "Ang simula at wakas ay kapatiran" (Brotherhood is the beginning and the end)--a statement that soundsprofound but is essentially meaningless, the kind of exciting, easy-to-remember slogan extolling unity and obedience the Soviet Union used to crank out by the thousands. Sid repeats many of these himself, with less and less conviction as adversity raises doubt in the pledges' minds--a condition that the frat eventually addresses, in the film's key scene.

An elaborately designed electric chair straps and all with a remote button is introduced, and the pledges are literally pushed to their physical and mental limits. A frat master (actor Chito Ponce Enrile, brother of Marcos' Defense Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile) explains: "Trust your frat. Hindi naman hinihingi ng frat ang hindi n'yo kaya (The frat doesn't ask for more than you can give)...ang importante ay makapagdesisyon kayo. Kailangan makipagdesisyon ang bawat isa sa inyo...(...what's important is that you decide. Each of you need to decide for yourself...)." The frat makes its case to the pledges in a reasonable, measured (but nevertheless authoritative) voice, not demanding but asking them to willingly put their faith in the group, put their faith in something bigger than themselves. As Anthony Burgess in his novel repeatedly asks to the reader (the repetitiveness--and urgency, in my view--markedly reduced in Kubrick's film): "What's it going to be then, eh?" It's I submit the hook with which a fascist organization or government wins undying loyalty from its followers: the carefully presented moment when a man is asked, pen poised in hand, to sign away above the dotted line.

But that's the plea; what seals the deal is sacrifice, preferably involving blood. We see hints of that in the contusions covering one pledge's chest, as he reveals he was coerced into participating in the electric-chair stunt; we see it more prominently later on when another pledge is killed by a rival gang and a full-fledged rumble takes place, literally an orgy of gore. Any breath or whisper of skepticism, of protest, of defiance is silenced--now and forever--once blood has been spilled; there's nothing like the (as Burgess put it) "red red krovvy on tap" to validate an idea beyond any possible doubt.

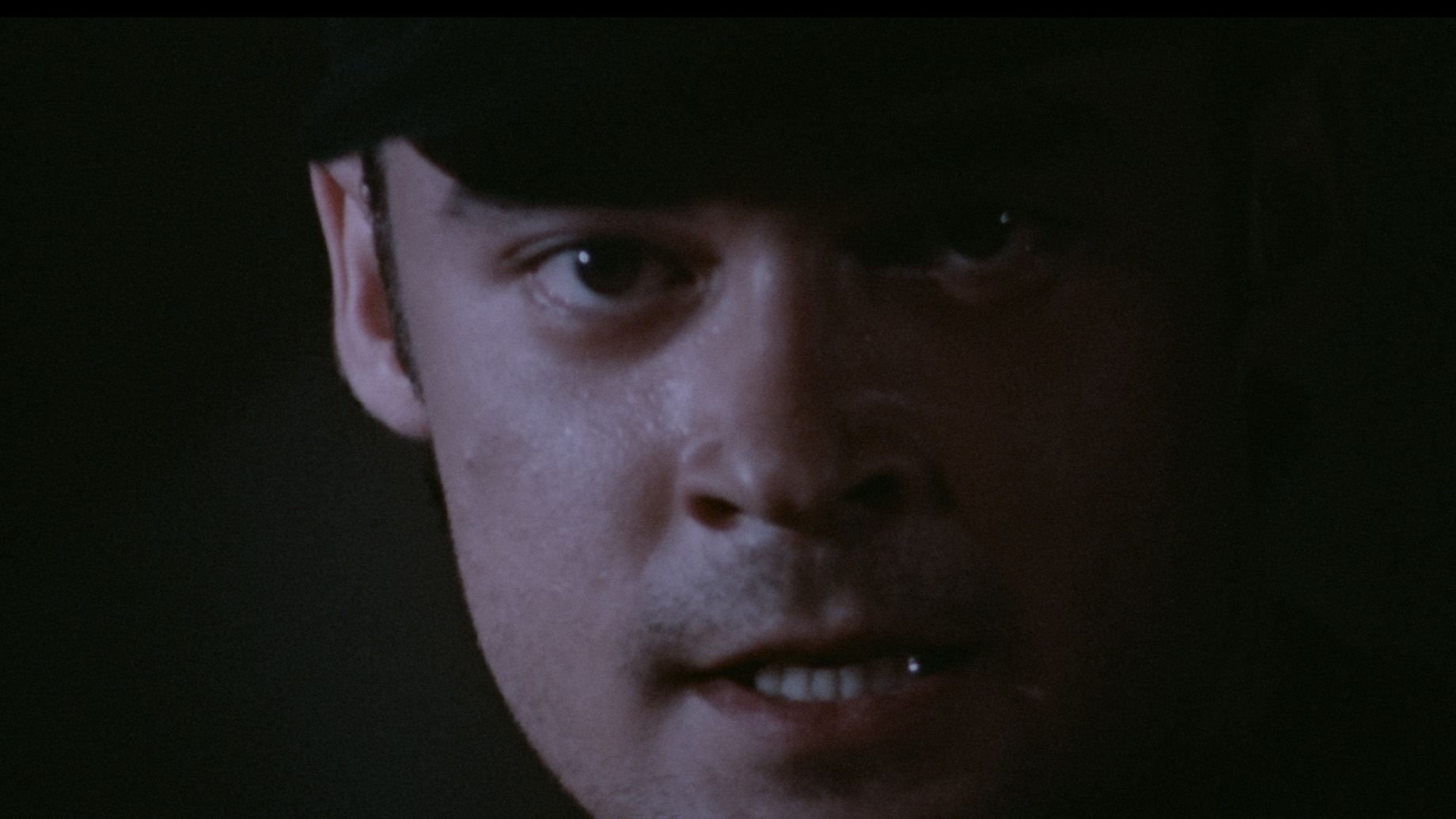

De Leon ends the film the way Kubrick ended his 2001, with the Star Child gazing straight through the screen at us, only where the Star Child radiates an air of serene transcendence, Sid Lucero's face--head slightly lowered, eyes level and direct--seems utterly drained of emotion, his lips mouthing the frat's principles with mechanized fluency ("Ang simula at wakas ay kapatiran!"). He is cured all right--of all reason, all intelligent thought, all sign or taint of humanity. He has evolved in opposite direction from the Star Child, towards total obedience, and has done so of his own free will.

Kubrick ends Clockwork on a joyous note, but it's a cynical joy, a passive despairing acceptance of the way things are--in effect, terrible. I much prefer Burgess' original novel, where an additional unfilmed chapter whispered the hint of a bizarre and bitter redemption, of the possibility of change. De Leon despite being (I suspect) every bit as misanthropic as Kubrick doesn't end his film the same way; that final shot of soulless Sid is his way of asking us to contemplate the entire trajectory of the man's character, from God-made fruit capable of sweetness to clockwork automaton, giving us a moment--on confronting this monstrous thing with the swinging paddle and mechanical moving lips--to mourn the irreplaceable, irrevocable loss.

Notes by Noel Vera republished by permission of the author

First published in Businessworld, 9/4/14. Reproduced on the Critic After Dark blog 9/4/14.

De Leon's reputation as a control freak is legendary and, to be honest, not entirely unfounded. Here he tells the story of one Sid Lucero, aspiring to enter the frat Alpha Kappa Omega: through Sid's eyes we see the initiation process, through his ears we hear the rules and philosophy of the fraternity, through his thoughts (done in voiceover) we learn of his reaction to the frat's unfolding nature. Oh, Sid spends onscreen time with his fellow pledges, who function as distinct supporting players (strangely the frat masters remain mostly undifferentiated walking ciphers), but it's only Sid's thoughts we hear, only Sid's consciousness that absorbs the film's narrative, even the corollary narratives of his brothers.

De Leon has rarely been shy about his admiration for legendary filmmaker Stanley Kubrick; if anything you can see Kubrick's influence on De Leon's geometrically meticulous visual style, his distant emotional tone, his tendency to subject characters to forces beyond their control. If Kisapmata is De Leon's tribute to Kubrick's The Shining (the former in my opinion being the superior film), Batch '81 would arguably be De Leon's Clockwork Orange, and not merely because of an overt Clockwork-style rock-music number, where a mannequin is eviscerated onscreen: specific events are mirrored (a head dunked in a tank of filthy water; a man strapped to a chair; one film beginning with a gang rumble, the other ending with same), crucial themes echoed ("Anong desisyon mo?" (What's your decision?) recalling Clockwork's onscreen query: "What's it going to be then, eh?"--both films focusing on the primacy and degradation of free will).

If there's a difference between the two I'd say it's one borne of circumstance: Kubrick was a well-funded filmmaker, with a healthy commercial relationship tangential if not completely dependent on mainstream Hollywood. De Leon is not without resources (he is the grandson of film matriarch Narcisa De Leon, of LVN Pictures) but his budgets, if not starvation poor, are modest, and he scales his ambitions accordingly. Where Kubrick's films are elaborately constructed and obsessively detailed mindscapes, the extravagant sets used eccentrically (the vast hotel in The Shining, the unending ship in 2001, the decadent mansions in Paths of Glory, Lolita, Barry Lyndon, and Eyes Wide Shut) De Leon goes the other direction, employing naturalistic environments (a family home, a frat house basement) expressionistically, transforming them into psychic traps where his characters gnaw desperately at each other and at themselves, seeking escape.

Hence the frat house in Batch '81, where much of the action takes place. As designed by longtime De Leon collaborator Cesar Hernando the rooms are claustrophobic spaces where people can scream freely unheard, too small for those confined (seven freshly hatched pledges) to avoid notice, too narrow for them to do anything other than ask "more please!" The rooms eliminate any notion of freedom, any possible lifestyle alternative (a frat-free college career, for one), any thoughts outside of the moment: you are in a world of pain, and endurance of that pain is the sum total meaning of your life (past and future--other than your pending membership--having been beaten out of your skull).

De Leon's cinematography has always been functional almost to the point of unimpressive at least on first viewing, though they do have a crispness of image and precision of effect few other filmmakers, Filipino or otherwise, can touch. For this production De Leon (with cinematographer Rody Lacap) lights the sets with brutal frankness, the sole source of light often apparently being an incandescent bulb or two. Kubrick employs similar lighting in several of his films (the prison stage show in Clockwork; the lunar excavation in 2001), but where Kubrick uses the harsh glare to herald a spectacular revelation--the results of a mind experiment, the climax of an alien civilization's patient manipulations--De Leon employs them for a more quotidian reason: to illuminate the truth without flinching, without evasion. To show physical and psychological violence unadorned.

Need to mention one of De Leon's most important collaborators--don't usually like to discuss acting as I subscribe to Robert Bresson's theory on the subject (no actors, no parts, no staging; being as opposed to seeming) but even I have to admit much of the force of the film is due to the performance of the late great Mark Gil as Sid. If Al Pacino does volatile like no other actor, and Robert De Niro intense interiority, Gil seems to do both well, flipping effortlessly from one (yelling as his friend is being killed before him) to the other (meditating on his batchmates' faithlessness). And where De Niro practiced Method to the point of eating his way to obesity for Raging Bull, I doubt if even he is capable of enduring what Gil endures in one particularly harrowing scene, involving surgical clamps. No CGI, no apparent prosthetics--prosthetics do not gradually turn red onscreen.

Finally, the script, by industry veterans Clodualdo del Mundo, Jr., Raquel Villavicencio, and De Leon himself: a clean, linear storyline that traces Sid's transformation from trembling neophyte to full frat brother. Aphorisms (presumably recorded by the writers from actual frat language) are constantly flung about during the rituals: "Ang simula at wakas ay kapatiran" (Brotherhood is the beginning and the end)--a statement that soundsprofound but is essentially meaningless, the kind of exciting, easy-to-remember slogan extolling unity and obedience the Soviet Union used to crank out by the thousands. Sid repeats many of these himself, with less and less conviction as adversity raises doubt in the pledges' minds--a condition that the frat eventually addresses, in the film's key scene.

An elaborately designed electric chair straps and all with a remote button is introduced, and the pledges are literally pushed to their physical and mental limits. A frat master (actor Chito Ponce Enrile, brother of Marcos' Defense Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile) explains: "Trust your frat. Hindi naman hinihingi ng frat ang hindi n'yo kaya (The frat doesn't ask for more than you can give)...ang importante ay makapagdesisyon kayo. Kailangan makipagdesisyon ang bawat isa sa inyo...(...what's important is that you decide. Each of you need to decide for yourself...)." The frat makes its case to the pledges in a reasonable, measured (but nevertheless authoritative) voice, not demanding but asking them to willingly put their faith in the group, put their faith in something bigger than themselves. As Anthony Burgess in his novel repeatedly asks to the reader (the repetitiveness--and urgency, in my view--markedly reduced in Kubrick's film): "What's it going to be then, eh?" It's I submit the hook with which a fascist organization or government wins undying loyalty from its followers: the carefully presented moment when a man is asked, pen poised in hand, to sign away above the dotted line.

But that's the plea; what seals the deal is sacrifice, preferably involving blood. We see hints of that in the contusions covering one pledge's chest, as he reveals he was coerced into participating in the electric-chair stunt; we see it more prominently later on when another pledge is killed by a rival gang and a full-fledged rumble takes place, literally an orgy of gore. Any breath or whisper of skepticism, of protest, of defiance is silenced--now and forever--once blood has been spilled; there's nothing like the (as Burgess put it) "red red krovvy on tap" to validate an idea beyond any possible doubt.

De Leon ends the film the way Kubrick ended his 2001, with the Star Child gazing straight through the screen at us, only where the Star Child radiates an air of serene transcendence, Sid Lucero's face--head slightly lowered, eyes level and direct--seems utterly drained of emotion, his lips mouthing the frat's principles with mechanized fluency ("Ang simula at wakas ay kapatiran!"). He is cured all right--of all reason, all intelligent thought, all sign or taint of humanity. He has evolved in opposite direction from the Star Child, towards total obedience, and has done so of his own free will.

Kubrick ends Clockwork on a joyous note, but it's a cynical joy, a passive despairing acceptance of the way things are--in effect, terrible. I much prefer Burgess' original novel, where an additional unfilmed chapter whispered the hint of a bizarre and bitter redemption, of the possibility of change. De Leon despite being (I suspect) every bit as misanthropic as Kubrick doesn't end his film the same way; that final shot of soulless Sid is his way of asking us to contemplate the entire trajectory of the man's character, from God-made fruit capable of sweetness to clockwork automaton, giving us a moment--on confronting this monstrous thing with the swinging paddle and mechanical moving lips--to mourn the irreplaceable, irrevocable loss.

Notes by Noel Vera republished by permission of the author

First published in Businessworld, 9/4/14. Reproduced on the Critic After Dark blog 9/4/14.

The Restoration:

Restoration by the Asian Film Archives (AFA), Singapore, using

the 35mm original camera negative, a positive print and the original sound

negative held in the AFA collection. The negative was affected by vinegar

syndrome, haloes and mould, and contained dominant green-hued defects on the

emulsion. As a result, parts were unusable and had to be integrated with shots

from the positive print. The film elements were scanned and digitally restored

at 4K resolution by L’Immagine Ritrovata in 2016. Director Mike de Leon and

cinematographer Rody Lacap supervised the colour grading. Mike de Leon was the

first Asian director to donate his works to the AFA in 2005, including his

films Kakabakaba Ka Ba? (1980), Kisapmata (1981), and Bayaning

Third World (1999).

Credits:

aka ΑΚΩ 81 | Dir: Mike DE LEON | Philippines | 1982 | 100 mins | 4K DCP (orig.35mm) | Colour | 1.85:1 | Mono Sound | English, Tagalog with Eng. Subtitles | U/C18+.

Production Companies: LVN Pictures, MVP Pictures, Sampaguita Pictures | Producers: Marichu MACEDA, Chona VERA-PEREZ | Script: Clodualido DE MUNDO Jr, Raqual N. VILLAVICENCIO, DE LEON | Photography: Rody LACAP | Editor: Jess NAVARRO | Production Design: César HERNANDO | Sound: Ramon REYES | Music: Lorrie ILUSTRE.

Cast: Mark GIL(‘Sid Lucero’) | Sandy ANDOLONG | (‘Tina’) | Ward LUARCA (‘Pecoy Lesdesma’) | Noel TRINIDAD (‘Santi Santillan’) | Ricky SANDICO (‘Ronnie Roxas Jr.’) | Jimmy JAVIER (‘Vince’) | Rod LEIDO (‘Arnulfo Enriquez’).

Source: Asian Film Archive, Singapore.

Credits:

aka ΑΚΩ 81 | Dir: Mike DE LEON | Philippines | 1982 | 100 mins | 4K DCP (orig.35mm) | Colour | 1.85:1 | Mono Sound | English, Tagalog with Eng. Subtitles | U/C18+.

Production Companies: LVN Pictures, MVP Pictures, Sampaguita Pictures | Producers: Marichu MACEDA, Chona VERA-PEREZ | Script: Clodualido DE MUNDO Jr, Raqual N. VILLAVICENCIO, DE LEON | Photography: Rody LACAP | Editor: Jess NAVARRO | Production Design: César HERNANDO | Sound: Ramon REYES | Music: Lorrie ILUSTRE.

Cast: Mark GIL(‘Sid Lucero’) | Sandy ANDOLONG | (‘Tina’) | Ward LUARCA (‘Pecoy Lesdesma’) | Noel TRINIDAD (‘Santi Santillan’) | Ricky SANDICO (‘Ronnie Roxas Jr.’) | Jimmy JAVIER (‘Vince’) | Rod LEIDO (‘Arnulfo Enriquez’).

Source: Asian Film Archive, Singapore.